Keith Wailoo, Professor of History and Public Affairs, Reveals Big Tobacco’s Exploitation of Black Communities

The author: Keith Wailoo is a professor of history and public affairs at Princeton, and currently serves as president of the American Association for the History of Medicine. His research covers the intersections of history and health policy, with specialties in drugs and drug policy, the politics of race and health, the interplay of identity, ethnicity, gender, and medicine, and controversies in genetics and society. In 2021, Wailoo received the Dan David Prize and was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. His award-winning books include Pain: A Political History (Johns Hopkins University Press), How Cancer Crossed the Color Line (Oxford University Press), and Dying in the City of the Blues: Sickle Cell Anemia and the Politics of Race and Health (University of North Carolina Press). Wailoo holds a Ph.D. in the history and sociology of science from the University of Pennsylvania, and a bachelor’s degree in chemical engineering from Yale University.

Excerpt:

I grew up in New York City in the 1970s in the era of blaxploitation — a term coined during my early years, describing a new genre of Black-themed films like Super Fly (1972) that trafficked in garish stereotypes of urban street life filled with criminality, sex, and new heights of coolness. Curtis Mayfield’s “Freddie’s Dead,” one of the film’s hit songs, was also the soundtrack to my early years. Bemoaning the death of a junkie “ripped up and abused” by drugs, it was a lyrical tragedy broadcast across the airwaves, a melodic warning about one man’s downward spiral into drug abuse: “another junkie plan, pushing dope for the man.” I first learned to be wary of pushers looking to get kids like me “hooked on dope” from these stark stereotypes, but growing up in the Bronx and Queens, I spotted real pushers soon enough. Street-corner hustlers as well as older teens trafficked in everything from marijuana and heroin to cocaine and quaaludes (which I first heard mentioned in my Bronx elementary school). One of my friends, intending to be funny by riffing on my name, called me Keith Quaalude.

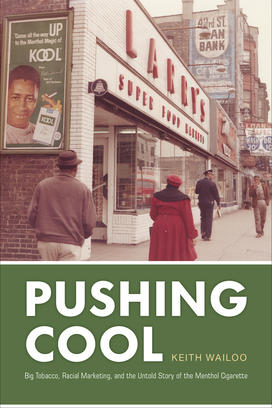

At some point between life in the Bronx and in Queens (where we moved next), I also became alert to another kind of push: the messages emanating from cigarette billboards. They were everywhere. New York was saturated with tobacco posters on buses and subways. Massive billboards lined streets and highways, featuring their own stark and stereotypical fantasies that pushed a popular and legal drug. Many of these ads promoted menthol cigarettes, known for the minty cool sensation they produced on the throat. The brand names are etched in my memory — Kool, Salem, Newport, and the now-defunct More. I remember the signature waterfall imagery, the smooth-looking Black men and women, and the carefree Black groups featured in the Newport ads.

Not far from our LeFrak City apartment in Queens, a new oversize 14-by-48-foot cigarette billboard appeared in 1976 at Woodhaven and Queens Boulevards near a busy shopping center. To me, it was just an ad, an unremarkable sight in a city bathed in outdoor advertising. It was only much later that I learned just how elaborate was the web that landed this particular sign in this specific neighborhood. Purchase Point, the Park Avenue company responsible for the Woodhaven billboard in my Queens neighborhood, boasted to the American Tobacco Company about its magnificent placement. Brightly illuminated, the bulletin loomed day and night over “the busiest area in Queens where within three blocks you will find four major department stores,” near “two of the largest private housing developments in Queens … (Park City and LeFrak City).” Purchase Point estimated that the “daily effective circulation” — the number of people seeing the tobacco ad every day from roadways — was 75,000. The number did not include “the estimated 20,000 pedestrians that pass this area daily nor the viewing available from the Long Island Expressway.”

Nor was this billboard unique. Surveying New York’s expansive billboard menagerie, an advertising manager for the American Tobacco Company boasted that he had just driven by “72 of the 127 [oversize] thirty-sheet posters … located in Manhattan, Bronx, Queens and Brooklyn.” This extensive coverage meant that American Tobacco’s “competitive position in New York is good,” but he bemoaned that R. J. Reynolds, an arch competitor, was “using almost all of their out-of-home media … to introduce [a new menthol brand] More cigarettes. The effect is overwhelming.”2 Unknown to me, these images, with their waterfall motifs and cooling messages, had arrived in my neighborhood after careful deliberations, extensive testing, and outreach to Black civic groups and communities — efforts crafted by Madison Avenue firms, psychographic consulting groups from Chicago to Princeton, and tobacco executives from Richmond, Virginia, to Winston-Salem, North Carolina.

In 1970s New York, all these pushers — of cocaine, pot, quaaludes, and cigarettes — stalked neighborhoods, but in different ways. Of course, I knew that smokers were also addicts, even if of a less threatening sort, hooked on a legal drug. I also knew that many New Yorkers worried about so many cigarette ads, seeing them as another dangerous drug push. Only a few years earlier, when I was ten, cigarette ads had been banned from the television and radio airwaves. City ordinances had been enacted to keep cigarette billboards away from schools. All this I knew well. What I was less aware of was how recently these billboard jungles had sprung up. They multiplied quickly in the aftermath of the 1970 TV and radio ban as part of the tobacco industry’s push to make up for the loss of national media channels, saturating urban markets closer to the points of purchase.

But why my neighborhood? And why menthols? From scanning Ebony and Jet magazines — Black-themed periodicals I read at my grandparents’ house in the Bronx — I knew that menthols were pushed as a “Black thing.” Ebony, which in 1972 questioned whether the rash of new Black-themed movies like Super Fly, Cotton Comes to Harlem, and Shaft were “culture or con game,” also ran ads for all the major menthol brands. The Newport ads were particularly striking, with their Menthol Kings making a direct appeal to togetherness, amusement, and Black identity. “After all,” asked Newport, “if smoking isn’t a pleasure, why bother?” At the time, I could not have known how the tobacco industry targeted Ebony, or how the magazine participated in the push to connect Black smokers to menthols in exchange for much-needed advertising revenue. Nor could I have known that this intense drive toward racial advertising was only in its adolescence; the push was no older than me.

I had no inkling that the billboard hovering over Woodhaven and the ads in Ebony were the product of something larger — the web of relentless, enterprising executives, researchers, and marketers who invited would-be consumers to see ourselves in a new light. These marketers studied not only the flow of people in the city but also hu-man behavior and racial group identity; the social researchers tracked changing habits in neighborhoods like mine; the admen shaped the therapeutic, calming imagery of More, as well as the other prominent brands of Kool and Salem; and myriad other consultants closely evaluated the effects of these messages on viewers’ preferences, brand choices, and sales. Nor did I understand how Black media outlets, civic organizations like the NAACP, politicians, and urban leaders (including some of the politicians whom I admired) channeled these messages, while also relying on Big Tobacco’s economic support for their enterprises. All were caught in the web that cigarette companies, and menthol makers in particular, had spun.

Looking back now, I see that my youth coincided with a particular chapter in menthol smoking’s racial history, an era defined by blaxploitation not only in film but also in tobacco marketing. It was an era in which menthol sales reached new heights, accounting for 30 percent of all cigarettes sales. The two trends — menthol and blaxploitation — went hand in hand. Ebony said about films like Super Fly that Black viewers would have to decide for themselves whether the imagery and message were “reflections of a glorious people — or trick-mirror, fun-house distortions of black truth.” Within a few years, the cultural high point of blaxploitation subsided on-screen, but tobacco marketing pressed on in the city.

New York’s ever-present billboard scene soon receded from my life, but only because my family moved to suburban New Jersey during my high school years. The sheer absence of billboard fantasies in a town named Maplewood was remarkable. The rustling waterfalls of Kool, the promise of mentholated Salem, the Marlboro Man — so relentless and dense in the city — were absent from my new leafy-green surroundings, even though they were readily visible in the nearby city of Newark. As I later learned, this urban-suburban divide in pushing tobacco and menthol was no accident. It was a product of careful study and social design, a disparity in the push that had a troubling racial and marketing logic. In the early 1980s, for example, the William Esty ad firm for R. J. Reynolds worried about its competitor brand “Kool’s strength … concentrated in those markets in which a high proportion of Black consumers reside,” and they told RJR executives that their “Salem Spirit” campaign could “gain brand share by focusing its couponing activity on poverty markets.” Their study ranked Newark as the number one such metropolitan poverty market, with some 33 percent of people living below the poverty level. Of course, the suburbs also had their problems, their drug users, and their economic worries. Tobacco researchers and consultants studied them, too, examining every social opportunity to sell. But the focus on “poverty markets” aligned neatly with the industry’s menthol strategy in this age of blaxploitation. No matter how regrettable poverty might be, marketers saw people in need, social alienation, or drug use in cities as opportunities to shape cigarette markets in general, and menthol markets in particular.

The experience of coming of age in this peculiar era of blaxploitation surely informs the questions I ask in these pages, many years later — questions about the geography of racial markets; questions about how menthol smoking found its way into the Bronx, Queens, and Newark, and into Black amusements, magazines, and consumer preferences; and questions about how these perverse images of Black masculinity and identity were created, and how this campaign was sustained for so long, with what effect. What I learned in researching this book and by delving deep into the heart of the tobacco industry’s archives is how these pushers and their supporters, as well as many influencers unknown to me in the 1970s, shored up these preferences, and how this house of menthol was built and maintained. Deception as a feature of commerce, life, and psychology was at its peak. Finally, I also learned how the foundations of this campaign were eroded, how the billboard era came to an end, beaten back by social developments beyond the industry’s power to control. Reflecting on these years of pushing cool, I still hear “Freddie’s Dead” playing in my head — a distant backbeat to the strange history of the menthol cigarette and the tragic business of making racial markets in America.

Reprinted with permission from Pushing Cool: Big Tobacco, Racial Marketing, and the Untold Story of the Menthol Cigarette by Keith Wailoo, published by the University of Chicago Press. © 2021 by The University of Chicago Press. All rights reserved.

Reviews:

“In Pushing Cool, Wailoo tells the fascinating story of how tobacco companies and advertising firms marketed menthol cigarettes, especially to African Americans. Diving deep into this untold history, he also brings essential insight into how the construction of pleasure-enhancing products and processes of racialization have enjoyed mutually informing histories well into the twentieth century.” — Samuel Kelton Roberts Jr., Columbia University

“This captivating, comprehensive book contains something to intrigue everyone—from lawyers to psychologists, marketers to historians. Pushing Cool is a unique and important work that deserves to be read widely.” — Andrea Freeman, University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa

No responses yet