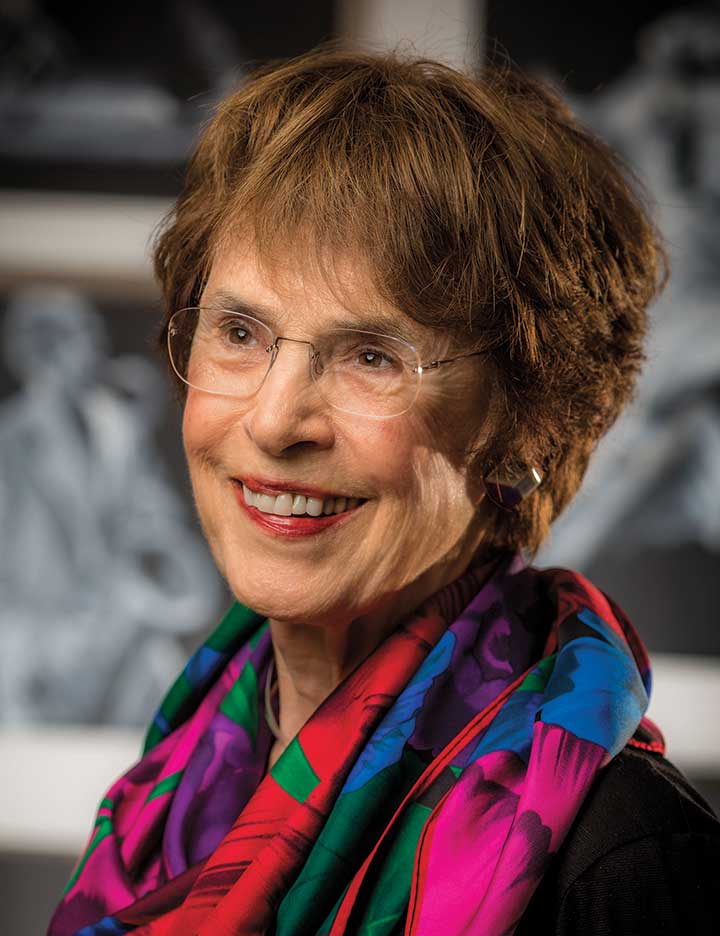

The Lady and the Tigers

When coeducation arrived, Halcy Bohen was tasked with women’s safety, success

“Oh, Halcy, I’ve got a problem. The board just decided to take women,” she remembers Bowen saying — meaning, by “problem,” the sudden administrative challenges. “What am I going to do? I need a dean of women!”

Bohen, who had served the University as an informal consultant and ambassador to the wives of professors who were being recruited, found herself with the position — not dean of women, officially, but rather assistant dean of students with special responsibilities for women. After much deliberation, the University chose to admit a small group of women — 101 freshmen, 171 in total — to matriculate in the fall. Bohen was charged with their safety and success.

When she interviewed for the job, she says, the male administrators who hired her suggested three ways to help integrate women into life on campus: “One, we should have kitchens; two, we need to have locks on the entryways; and three, we’d better have a dance program.” It would be her job to figure out what else would be needed, she says.

The staff dutifully put a kitchen in Pyne Hall, the building that served as a dormitory for the entering women. They also arranged to have electric locks installed on the doors to Pyne Hall. Princeton hired a dancer and choreographer from New York City, Ze’eva Cohen, to teach dance in a studio in Dillon Gymnasium. To the administration’s surprise, of the 60 students who signed up for the first round of dance classes, 50 were men. This was the first hint of what became a pattern, Bohen says: “The bottom line — the things they thought women needed were in fact things that men needed, too.”

In her office in West College, Bohen, then 31, greeted visitors in front of a hanging tapestry that displayed a picture of the Woodstock music festival. Students came with issues of every kind: roommate disputes, health problems, questions about when students could visit each other’s rooms and what to do if a roommate brought in a visitor at 2 a.m. Abortion was illegal in those years; staffers quietly put students with unwanted pregnancies in touch with a network of clergy who helped women to find sympathetic doctors, Bohen says.

That first class with women all four years graduated in 1973, barely a decade after the publication of Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique. Even women with expensive educations questioned whether they should pursue careers. (Bohen consulted her children’s pediatrician before taking the job as dean, she says: “I asked him whether I would harm my children, and he said, ‘Absolutely not. Do it.’ ”) To help students think through these issues in their own lives, Bohen organized small-group discussions where students could ask questions of dual-career couples with children. An audience of 40 students in the first year turned into an audience of 130 students in the next.

Bohen helped to grow the residential-adviser program. At annual fall retreats at Blairstown camp, she trained advisers to get to know the freshmen assigned to them, keep tabs on their circumstances, listen with compassion, and refer students to support systems within the University if need be.

To the University’s surprise, of the 60 students who signed up for the first round of dance classes, 50 were men. This was the first hint of what became a pattern, Bohen says.

Sex on campus was a subject of breathless interest among alumni and journalists. LIFE magazine ran a photo spread on Princeton coeducation with lots of close-up shots of women in miniskirts. Most women on campus wore slacks, Bohen says. “I’ve received quite a bit of hate mail,” Bohen told a newspaper reporter in 1969. “Comments on the promiscuity of the coeds to pleas that I will personally see to keeping these girls virtuous.”

In 1973, Bohen gave a talk to the Class of 1950 at the Princeton Club in New York City, on “Changing Sexual Behavior and the Campus.” Although the long-term consequences of coeducation were still to be seen, she told her audience, already evidence showed that men and women flourished in each other’s company in ways that had little to do with sex. At Radcliffe, she said, researchers had found that “not only do women in coed dorms develop easy and multiple friendships with their male neighbors (whereas those in single-sex dorms usually had only dating relationships), but their friendships with women also became more positive, affectionate, and trusting.”

“They have learned to ‘be themselves’ — as smart, or funny, or serious as they really are — around both sexes,” Bohen added. “They no longer have as many fears about being ‘unfeminine.’ Their lives are more intellectually interesting and more fun.”

As dean, Bohen was “a godsend” to the women of Princeton, according to a recent book on coeducation by professor emerita of history Nancy Weiss Malkiel, but her contributions helped the whole of the campus to flourish — and can still be felt in the daily life of the University today.

Bohen served as assistant dean for eight years. “I relished the opportunity to help advance women’s opportunities and especially loved the engagement and fun with students — as well as the opportunity to get to know, learn from, and develop friendships with so many others in the University community — many of which are still integral parts of my life,” she says. Today, she has a dual career, as a psychologist with a private practice in Washington, D.C., and as a visual artist. She has exhibited her art widely, and more than 250 of her works are in private collections.

The first days for women on campus found the community tentative, timid, exasperated, uncertain. After the freshmen’s move-in day, Bohen told reporters that the women, embarrassed by the profusion of men offering, in the daytime, to give them a “tour of campus” and, at night, to bring them a drink, were waiting eagerly for classes to begin: “They hope to find, in the academic side of life, more relaxed and open relationships with the men.” The biggest complaint from her charges, Bohen said, was that “they’re fed up with cutesy stuff about coeducation, especially the press and photographers.”

In time, the journalists left the campus, the administration found ways to address student needs that had long existed but never been considered, and the men and women of Princeton found they enjoyed one another as utterly ordinary classmates. All of that was soon to come when, at the beginning of freshman week, Admission Director John Osander ’57 — standing beside Bohen — addressed the new class: “Gentlemen and — at long last — ladies, I officially present the Class of 1973.”

3 Responses

Belinda Schuster s*77

5 Years AgoAdvising at Princeton Inn

In 1972, Halcy hired my graduate-student husband, John A. Schuster *77, and me, a grad student at Rutgers, to be residential advisers at the Princeton Inn, not long after it had been transformed from a hotel to a coeducational dormitory. I recall feeling quite prepared for this position of responsibility as we were already approaching our mid-20s and we each had prior experience in living in coed residences.

At the time, I had no clue that the Princeton elders viewed women as a potential problem or possible threat to the institution. I didn’t think we were part of a revolutionary, bohemian, left-leaning educational experience or movement. Keep in mind that in those days we thought it natural not to trust anyone over 30! We often worried about our relationship with our boss, Halcy, and indeed the master of the Inn, Bert Sonnenfeld *58, whom, despite their age and authority-figure status, we related to rather well.

Although our main duties mirrored those that Halcy mentioned, we always enjoyed the company of the students and felt we contributed by providing role models for life and work after graduation. By now, some of our former advisees have children who have graduated from Princeton. We sometimes wonder if we are mentioned when they talk about their first-year experience.

Photo: Jeffrey MacMillan p’14

Robert Klatskin ’73

5 Years AgoBrought Back Memories of Princeton Inn College

Great to see Belinda Schuster s*77’s letter about advising at Princeton Inn College (Inbox, April 8). I remember Belinda as I was a sophomore during the first year PIC was open for students. A great experience. Bert Sonnenfeld *58 was a brilliant master and coach, and the three years I lived there will be in my memories always.

John J. Wheaton ’78

4 Years AgoPrinceton Inn

I'm a graduate who moved into what was then known as Princeton Inn College when I was a sophomore. My first year there I had a nice roomie, a fellow from the same high school as I was. For my junior and senior years, I had singles — and enjoyed it!

It's been a long time since I've visited Princeton. Once I get my vaccination against our latest disease threat, I hope to visit Princeton and my former places of residence. Plus, I hope to visit the offices of The Daily Princetonian and the Comparative Literature department. I was a reporter and editor of the 'Prince' and a CompLit major. Puedo hablar espanol. Posso falar portugues tambem.