The Legacy of Hobey Baker ’14

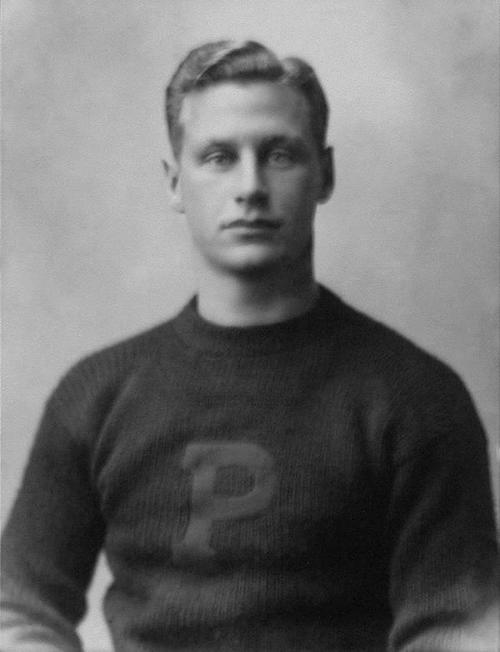

Forty-five years — almost half a century! — yet the remembrance of him is redolent enough to summon up the sight of the crowd getting to its feet and screaming “Here he comes!” as he took the puck from behind his net and started up the ice, gathering speed until finally his skates seemed a streak of chain lightning and the Greek-god blondness of him almost a blur

It is odd how his name keeps coming up after all these years, the mere mention of it evoking the past so poignantly that, for a little while, it seems almost as if her were among us still, the grace of him making wonderlands of all our winters – he whose gift was to be glimpsed so briefly. But whom the gods love and so forth – nor did that ever seem so tragically true as on that December morning when he perished over an alien land.

Of forty-five years all but two days have fled since then, but the image of him remains as it was in the swiftness and sinew of his youth, when, of all college boys, he was the most golden and godlike. Forty-five years – almost half a century! – yet the remembrance of him is redolent enough to summon up the sight of the crowd getting to its feet and screaming “Here he comes!” as he took the puck from behind his net and started up the ice, gathering speed until finally his skates seemed a streak of chain lightning and the Greek-god blondness of him almost a blur, making hearts leap up.

In the magic of moments like that he was more miracle than man. Nor is this legend, either, for even the most circumspect of hockey devotees who saw him are agreed that he was very, very special indeed.

And to have played with or against him – ah, that must have been something: And as for having defeated him – well, there is a man who, on a night in 1914, came out onto the ice and scored the goal that was to win for Harvard after more than forty minutes of sudden death. Now that man is full of honors and fame, for he is Leverett Saltonstall, who, on winter morning, sometimes plays hockey with his grandchildren, and always the stick he uses is the one with which he scored the goal for Harvard over Hobey Baker.

For that is the way that men who saw Princeton play in those years refer to it – as Hobey Baker. Nor can anyone argue about that, either, for Hobart Amory Hare Baker (1892-1918) somehow seemed Princeton in that age. But, before that, he had been the pride of St. Paul’s, where he played on its rinks on the afternoons of peace on earth and where, now, his spirit inspires. Yet presently there was war and he joined the Lafayette Escadrille.

Around eleven o’clock on the morning of December 21, 1918, he received his discharge and was on his way from headquarters when he decided to take a final flight in the Spad that was colored in the orange and black of Princeton.

But something changed his mind and he decided, instead, to make sure that one of the other planes, which had been damaged a few days before, had been properly repaired. Apparently it had not, for when he was 500 meters above the field, the motor suddenly stopped. They buried him in the rain, with the band playing “Nearer My God to Thee.” Then his men fired three volleys and taps sounded plaintively across the French countryside – and he had become part of the ages.

That was so very long ago, and yet, in a way, he was in Madison Square Garden on this grey December afternoon when the boys in his old school played a game of hockey against St. Mark’s.

At five in the morning, the 400-or-so students had risen from their beds and made ready for the train ride that would take them through the frozen New Hampshire countryside to the Garden and, as well, to their homage to Hobey. It is odd, is it not, that the departed, no matter how dear, should inspire such invocation – but that is the way he haunts a whole school, and from generation unto generation. You say “Hobey Baker” and all of a sudden you see the gallantry of a world long since gone – a world of all the sad young men, a world in which handsome young officers spent their leaves tea-dancing at the Plaza to the strains of the season; a world in which poets sang of their rendezvous with death when spring came round with rustling shade and apple blossoms filled the air.

It was a world in which young men soared into the sky and fell in flames. There was such gallantry, such great grace, in that world. That was Hobey Baker’s world, and it is good that it is not forgotten. For if it seems odd how his name keeps coming up after all these years, it is an oddness devoutly to be desired. And, on days like this one, it bespeaks our return, if only for a little while, to the time before we all of us fell from grace.

To this day Hobart Amory Hare Baker remains Princeton’s athletic Chevalier Bayard, sans peur et sans reproche. President Hibben thought in him “the spirit of the place was incarnate,” Scott Fitzgerald wrote of him “an ideal worthy of everything in my enthusiastic admiration, yet consummated and expressed in a human being who stood within ten feet of me.” Baker Rink was built by subscription of his admirers, who included men from 39 colleges, among them 172 from Harvard and 90 from Yale. Harvardman George Frazier – from whose column in the Boston Herald this thoughtful essay is reprinted by permission – might have mentioned that he was also a great football captain, a bareheaded halfback specializing in booming drop kicks and dramatic flying tackles. - Editor

This was originally published in the February 8, 1963 issue of PAW.

No responses yet