Letters from the Lost Generation: Princeton and the Papers of Sylvia Beach

From the PAW Archives

In early December 1964, the University announced it had acquired the papers of Sylvia Beach, the famed publisher and Paris bookseller who befriended and supported leading literary figures in the 1920s and ’30s, including James Joyce and Ernest Hemingway.

Beach, who spent most of her life in Paris and died in 1962, had grown up in Princeton, where her father, Rev. Sylvester Beach 1876, was a pastor at First Presbyterian Church. “Princeton, with its trees and birds, is more a leafy, flowery park than a town, and the Beach family considered itself lucky,” she wrote in her 1959 memoir, Shakespeare and Company, named for her English-language bookstore in Paris.

Librarians were most excited about Beach’s literary life, not her local roots, and Howard C. Rice Jr., then the assistant librarian for rare books and special collections, told The New York Times that the collection “promises to be a rich quarry for those interested in the literary figures with whom she was acquainted.”

Rice knew the collection well: In the spring of 1964, he spent several weeks at Beach’s former residence cleaning out her letters and books and readying them for shipment to Princeton. After the news was made public, Rice wrote about Beach’s papers for PAW (see full text below). A book of Beach’s letters, edited by Keri Walsh *09, was published by the Columbia University Press in 2010.

The Papers of Sylvia Beach

By Howard C. Rice Jr.

(From PAW’s Feb. 16, 1965, issue)

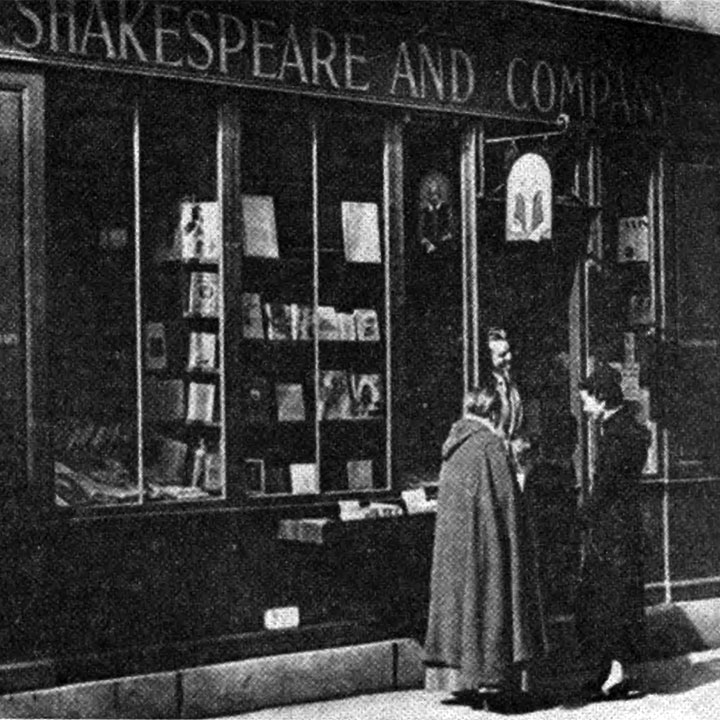

As every student of the “Lost Generation” knows, the Paris bookshop, Shakespeare and Company, of Sylvia Beach was a meeting-point — almost the meeting-point — for French, English, Irish and American writers during the 1920s and 1930s. (In A Moveable Feast Hemingway wrote of her, “No one that I ever knew was nicer to me.”) The acquisition of her extensive papers and books by the University Library, therefore, is a major event.

The collection, which had remained in Miss Beach’s Paris apartment at 12, Rue de l’Odéon since her death there in October 1962, was acquired earlier this year from the Sylvia Beach estate, through the generosity of Graham D. Mattison ’26 and with the interest and support of Miss Beach’s surviving sister, Mrs. Feredric J. (Holly Beach) Dennis of Greenwich, Conn. I spent several weeks in Paris last spring preparing the Beach collection for shipment to the United States. It is now at Princeton, where it is in the process of being organized, and will, it is hoped, be available for the use of scholars this year.

Sylvia Beach, born in Baltimore, Md., in 1887, was the second of three daughters of Eleanor Orbison Beach and the Reverend Sylvester Woodbridge Beach ’76, for many years pastor of the First Presbyterian Church in Princeton. She first visited Paris in the early 1900s, when her father was director of a center for American students and assistant pastor at the American Church. Frequent trips abroad followed this first sojourn. After World War I (a part of which she spent in France), Miss Beach, with the encouragement of Adrienne Monnier, who presided over La Maison des Amis des Livres at 7, Rue de l’Odéon, opened a bookshop and lending library of her own specializing in English and American books. “Shakespeare and Company,” as she called it, opened its doors in 1919 at 8, Rue Dupuytren, a small street on the Left Bank in the neighborhood of the Ecole de Medecine. In 1922 the shop moved to 12, Rue de l’Odéon, across the street from Mlle Monnier’s establishment, where it remained until 1941. In that year, to forestall confiscation by the Nazi occupants of Paris, Shakespeare and Company “vanished” overnight to a vacant upstairs apartment at the same address. After World War II (during which she spent six months in an internment camp at Vittel) Miss Beach maintained her residence at 12, Rue de l’Odéon, but did not reopen her street-floor bookshop there. During the two decades separating World Wars I and II Shakespeare and Company served as a port of call for American visitors to Paris, for expatriate writers of the so-called “Lost Generation,” and as a center where French writers, translators and scholars deepened their acquaintance with English and American literature. To her other activities Miss Beach soon added that of publisher, acquiring a portion of her fame as the publisher, in 1922, of James Joyce’s Ulysses, which she distributed as long as it remained a banned book in England and the United States, and, in 1927, of his Pomes Penyeach. There followed, in 1929, also under the imprint of Shakespeare and Company, a volume of studies of Joyce’s Work in Progress (later incorporated in Finnegans Wake), by fourteen contributors, entitled Our Exagmination Round His Factification for Incamination of Work in Progress.

Princeton Rescues

Protecting Joyce’s work against piracies was one of the frustrating subsidiary tasks created for Miss Beach by her publishing ventures. In one such episode her American “home town,” Princeton, played an essential part. In April 1931, upon learning that an unauthorized edition of Pomes Penyeach was being printed in Cleveland, Ohio, on the grounds that the work was not copyrighted in the United States, “S.B.” straightway requested “S.W.B.,” her father in Princeton, to arrange with Princeton University Press for a special printing of Pomes for the purpose of securing copyright. The business was handled most expeditiously, through Tomlinson of the University Press, and early in May fifty copies of a small twenty-page pamphlet in gray wrappers were on their way to Paris, while two additional copies were sent to the copyright office in Washington. This edition — described in Slocum and Cahoon’s Joyce bibliography under No. A 25, and now much prized by Joyce collectors — includes on the title page the name of Sylvia Beach and date 1931, with “Copyright 1931 by Sylvia Beach” and “Printed in the U.S.A.” on the verso. There is no mention, however, of Princeton or of Princeton University Press. According to a memorandum on the subject preserved among Miss Beach’s papers, the charges for this P.U.P. printing of P.P., including copyright expenses, were $27.06.

Her Memoirs

Miss Beach has herself told the story of her career in a volume of memoirs published by Harcourt, Brace and Co. of New York in 1959, under the title Shakespeare and Company, which was also issued by Faber and Faber in London, and subsequently in French, German and Italian translations. This book provides a key and summary guide to the collection of manuscripts, books, pictures and other souvenirs now at Princeton. Indeed, it is evident from a collation of the book with the collection that, during the 1950s, when Miss Beach was marshalling her memories, she was concurrently ordering her papers and books. Thus, the book itself may be characterized as a collection of documented memories and the collection as the documentation for the book. In 1959 Miss Beach had a major share in the organization of the exhibition, “Les Années Vingt, Les Ecrivains Americains a Paris et leurs amis, 1920-1930,” held at the Centre Culturel Americain in Paris, under United States Embassy auspices. The display was based to a large extent on Miss Beach’s collection, as was the revised version of the same exhibition held at the USIS gallery in London the following year under the title, “Paris of the Twenties: An Exhibition of Souvenirs of British, French and American Writers, from Shakespeare and Company.” The notable printed catalogue of the Paris exhibition, to which Miss Beach contributed an introduction, lists many of the items now in the Princeton Library. Still others are included, under the subheading “Petit Memorial de Shakespeare and Company,” in Sylvia Beach, 1887-1962, a volume of tributes assembled by her friends Maurice Saillet and Jackson Mathews (published in the Mercure de France, August-September 1963 issue, and also separately, with added illustrations).

With the exception of Miss Beach’s “Joyce Collection” — that is, manuscripts which James Joyce had given to her and letters which he had written to her — which she relinquished in 1959 to the University of Buffalo Library, the collection at Princeton is a substantially complete personal archive, reflecting all aspects of Sylvia Beach’s life. The correspondence files include letters from such American writers as Harriet Weaver, Hilda Doolittle, Ezra Pound, Sherwood Anderson, Gertrude Stein, Ernest Hemingway, Archibald MacLeish, Robert McAlmon, T. S. Eliot, William Carlos Williams, Allen Tate, Alice B. Toklas, Marianne Moore, Katherine Anne Porter, and Richard Wright. George Antheil — the “bad boy of music,” who came to Paris from Trenton, New Jersey, and who lived for a time in the mezzanine-floor apartment above the Shakespeare and Company bookshop — is represented in the collection by letters, musical scores, and by the original piano player rolls (inscribed to Sylvia Beach) which served at the world premiere of his Ballet Mecanique in Paris in 1926. F. Scott Fitzgerald ‘1 7 makes a brief appearance with Miss Beach’s personal copy of his The Great Gatsby, in which the author drew a picture commemorating the “Festival of St. James,” a dinner held in July 1928 in Adrienne Monnier’s apartment, at which the Fitzgeralds made the acquaintance of James Joyce.

Correspondents of English or Irish origin include, in addition to Joyce, Gordon Craig, Arthur Symons, Ford Madox Ford, Frank Harris, Norman Douglas, Ivy Litvinov, Richard Aldington, Stuart Gilbert, Cyril Connolly, D.H. Lawrence, Stephen Spender, and Dorothy Richardson. French friends occupy an equally important place in the collection, as they did in Miss Beach’s life: for example, Adrienne Monnier, Valery Larbaud, Leon-Paul Fargue, Jean Schlumberger, Paul Valery, Andre Gide, Jules Romains, Jean Giono, Andre Chamson, Jean Prevost, and Henri Michaux (whose A Barbarian in Asia, translated by Sylvia Beach, was published in New York by New Directions in 1949).

Complementing the letters are books by the above-named writers, many of them first editions inscribed to Sylvia Beach. There are also ephemeral pamphlets, magazine publications of their work, and other material about those whose careers Miss Beach followed with special attention, and almost maternal interest, as long as she lived. Little magazines published on the Continent by English and American expatriates, as well as books issued by such Paris-based enterprises as William Bird’s Three Mountains Press, Robert McAlmon’s Contact Editions, and Harry and Caresse Crosby’s Black Sun Press, account for another interesting — and now hard-tocome-by — group of publications. Miss Beach’s portrait gallery — which once adorned the walls of Shakespeare and Company, and more recently those of her private residence — has also come to Princeton. Informal snapshots and more formal portraits, many of them inscribed by the subjects and some of them the work of “name” photographers like Gisele Freund and Man Ray, provide a visual record of Miss Beach’s wide circle of acquaintances. Among the original works by the French artist, Paul-Emile Becat, are oil portraits of Adrienne Monnier (the painter’s sister-in-law), done in 1921, and of Sylvia Beach (1923); pencil portraits of Miss Beach (1926) and of her father, the Reverend Sylvester Woodbridge Beach (1927); a pencil portrait of Havelock Ellis (1924); and a double portrait, also in pencil, depicting James Joyce and Robert McAlmon in 1921. Finally, mention should be made of several mementoes of Shakespeare and Company: the familiar red and blue signboard, painted by Marie Monnier-Becat, which hung from a bar above the door of the shop; the Staffordshire bust of the “Patron Saint,” presented by Lady Ellerman; the detachment of toy soldiers representing George Washington and his staff, supplied by Valery Larbaud to stand guard over Shakespeare’s house; and the framed scraps of Walt Whitman manuscripts which Sylvia Beach’s Aunt Agnes Orbison had once rescued from a wastebasket when on a visit to the old poet in Camden.

The Sylvia Beach Collection promises to be a rich quarry for those interested in the literary figures with whom she was acquainted, as the above roll call of names — far from complete —will indicate. Nevertheless, when seen as a whole, the collection is above all a reflection of Sylvia Beach herself, a personality who will long command respect for her own sake and not merely as one who lived in the reflected glory of others. The role of a prophet of the Twenties, which was thrust upon her during the last and what has been described as “the official period” of her life, was one that she accepted with characteristic conscientiousness, generosity and humor, but with a grain of salt, and without ever losing her bearings or sense of proportion. She was often distressed to find that people confused the literary life with the café life of the Paris Twenties. The name of Sylvia Beach inevitably appears in the many published memoirs of this period, which tell a great deal about who thought what about whom. But, as Katherine Anne Porter has recently pointed out in her perceptive sketch, “Paris: A Little Incident in the Rue de l’Odéon” (Ladies Home Journal, August 1964), although these recorded memories often clitter with malice, hatred and jealousy, none of them speak meanly of Sylvia Beach.

The French novelist Jean Schlumberger, when inscribing one of his books to her, characterized her as “Sylvia Beach, ambassadrice des lettres.” Another of her French friends, the novelist Andre Chamson (now Director of the National Archives of France), has developed this theme in a tribute entitled “Le Secret de Sylvia,” which appeared in the memorial volume mentioned above. Recalling that it was thanks to Sylvia Beach that he made the acquaintance of F. Scott Fitzgerald, Chamson concludes his reminiscence with these words: “Sylvia carried pollen like a bee. She cross-fertilized these writers. She did more to link England, the United States, Ireland and France than four great ambassadors combined. It was not merely for pleasure of friendship that Joyce, Eliot, Hemingway, Scott Fitzgerald, Bryher and so many others so often took the path to Shakespeare and Company, in the heart of Paris, to meet there all these French writers. But nothing is more mysterious than such fertilizations through dialogue, reading or simple human contact … I know, for my part, what I owe to Scott Fitzgerald. … But what so many others owe each other, is Sylvia’s secret.”

In recognition of Sylvia Beach’s role as ambassadress of letters, a substantial segment of the books which once formed part of the stock of Shakespeare and Company has been presented, on behalf of the University, to the University of Paris, for use in the Institut d’Etudes Anglaises et Americaines. These books might be described as a “basic library of English literature,” for the Shakespeare and Company “lending library” was for more than a mere circulating library for current reading. French teachers, students and English scholars, as well as translators and writers of the twentieth century, were in the habit of finding there, alongside the avant-garde writers of the twentieth century, not only Shakespeare, but also, in his company, the eighteenth-century novelists, the Romantics and the Victorians. Such books, which Miss Beach brought into France, with persistence and discrimination, from across the Channel or the Atlantic, may now continue their ambassadorial and fertilizing role among new generations at the Institut’s library, located in the Rue de l’Ecole de Medecine, where Sylvia Beach lived for more than four decades.

Even though Sylvia Beach’s name is associated with the Rue de l’Odéon, it is not inappropriate that a collection of her papers and books should now find a home in Princeton. Speaking in her memoirs of her very first visit to “the spot where such important things in my life were to happen,” she recalls that the eighteenthcentury neo-classic facade of the Odeon, the theatre standing at the head of the street, reminded her somehow “of Colonial houses in Princeton.” The first chapter of these memoirs evokes the years spent in Princeton with her family in the days of Woodrow Wilson. “Princeton,” she comments, “with its trees and birds, is more a leafy, flowery park than a town, and the Beach family considered itself lucky.” After Sylvia Beach’s death, her ashes were brought to Princeton for interment in the family plot in the Princeton Cemetery.

In the autumn of 1959, on her last visit to Princeton, Miss Beach had a glimpse of the University Library, where she took keen delight in examining Audubon prints and drawings (her memory flitting back to the birds she knew at her cottage at Bourre on the banks of the Cher, or at her chalet high above the Lac this Deserts in occasion, Savoy). She seemed, upon this occasion, far less interest in talking about the writers of the Twenties than she was in seeing the parsonage in Library Place, or in finding out if the families on Witherspoon Street still named their little boys Sylvester, as they had in the days when her father was their pastor.

No responses yet