Oct. 22, 1936 — Sept. 2, 2022

The simple pencil is a marvel of complexity. Though it appears mundane, its principal components — wood, graphite, aluminum, and rubber — come from around the world, and getting even one to market requires the cooperation of thousands of people. For this reason, economist Milton Friedman thought pencils represented the culmination of free-trade capitalism. In a similar vein, Eberhard Faber IV ’57, whose family name still adorns countless numbers of those unmistakable yellow pencils, had layers and dimensions that might not have been apparent at first glance. Pencils, in fact, were hardly the most interesting thing about him.

Born into one of the country’s preeminent manufacturing families, tragedy nevertheless marked his early life. In 1945, at only 9 years old, he was swimming at the Jersey shore with his father, Eberhard Faber 1915, when the pair were pulled out by a rip tide. Family rushed into the surf and rescued Faber, but his father drowned.

Just two years after his father’s death, at the age of 11, Faber was a regular on the popular radio program Child’s World, where he once interviewed his idol, Jackie Robinson, and was himself the subject of a profile in Life magazine. He enrolled in Princeton at the age of 16 and became chair of The Daily Princetonian.

Faber was proudest of writing the Prince’s lead editorial on April 24, 1956, which he signed with his own initials, supporting the University’s refusal to interfere when the Whig-Cliosophic Society invited alleged Communist spy Alger Hiss to speak on campus. Taking aim at Hugh Halton, the University’s Catholic chaplain, Faber wrote: “In denouncing the trustees’ position Halton implied that the undergraduate is not free to learn — only subject to the beliefs of his betters. He must not develop his own mind through personal judgment, but rather accept unthinkingly the prejudices of his teachers. We consider this to be true brainwashing.”

“If Eb Faber had wanted to be a writer, I think he would have been a good one,” suggests Robert Caro ’57, who worked with Faber on the Prince staff. “As it was, he displayed on The Daily Princetonian the qualities that made him such a successful executive in later life, stepping into a somewhat chaotic staff situation and sorting it out with a gentleness and firmness that I still remember with admiration.”

After teaching in France on a Fulbright scholarship, Faber returned to the United States, where it was inevitable that he would eventually join the family business, which also produced erasers, rubber bands, markers, and art supplies. Ancestors had been making pencils in what is now Germany since the mid-18th century. Shortly after Faber’s great-grandfather, John Eberhard Faber, emigrated to America in 1848, he started his own pencil business, building what is believed to be the first lead pencil factory in the United States. Eberhard Faber Co., as the American branch was called, and their German cousins, A.W. Faber-Castell, were commercial rivals for more than a century.

After becoming CEO in 1973, Faber returned the company to profitability; at its peak, it manufactured more than a third of the pencils sold in the United States. In 1987, though, he sold Eberhard Faber to Faber-Castell, thus reuniting the family name.

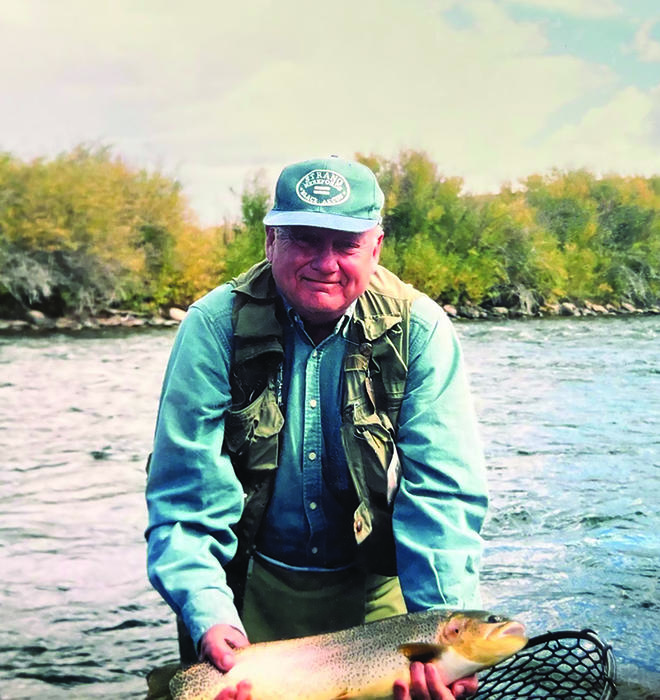

In later years, Faber served on numerous charitable, educational, and corporate boards, including the Philadelphia branch of the Federal Reserve. In that capacity, he bonded with Paul Volcker ’49 over their shared love of fly fishing. Faber wrote a profile of the Fed chair for Fortune magazine in 1986, assessing Volcker as follows: “You can joke with him, but you are never in doubt that he knows what he wants and will not easily be deflected. Finally, behind the clouds of cigar smoke and the oracular pronouncements is a man who genuinely likes people. And also likes trout.”

Fly fishing was only one of Faber’s passions. Chess was another; he eventually earned a ranking of National Master from the U.S. Chess Foundation. Until shortly before his death, he could also be found up to five times a week playing poker in high-stakes games at the Mohegan Sun casino in Connecticut. In his father’s obituary, Faber’s son, Eberhard “Lo” Faber *12, added a bit of cross-hatching to a colorful life, writing, “He [also] loved raw oysters, lobster, steak tartare, unfiltered cigarettes, good wine, and ridiculously strong martinis.”

Even decades after selling the pencil business, Faber remained proud of his family’s rich commercial heritage.

“My father liked to say that the Encyclopedia Britannica attributed the actual invention of the pencil to our ancestor,” Lo Faber laughs in an interview. “But that the article needed to be taken with a grain of salt because it was also written by my grandmother.”

Mark F. Bernstein ’83 is PAW’s senior writer.

No responses yet