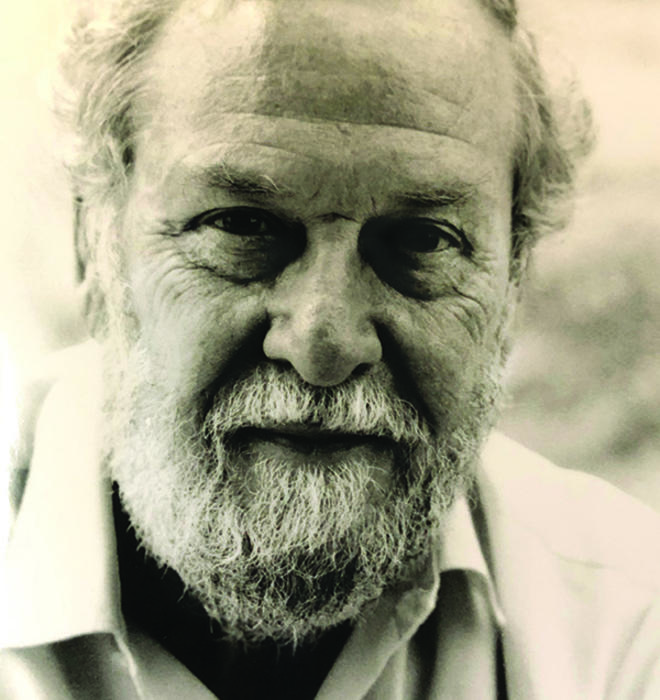

Feb. 5, 1928 — Feb. 23, 2022

There’s a story about Edmund Keeley ’48 — “Mike” to his friends — that captures his famously precise approach to translation. It goes like this: So dogged was the professor in his quest to understand the exact meaning of every word, every tiny piece of punctuation in the work of Greek poet George Seferis, that he talked his way into Seferis’ apartment.

After talking for six hours, a bleary-eyed Seferis gave up and simply stared at Keeley. From the next room, Seferis’ wife called out, “Give the young man a comma, George, help him, for heaven’s sake.”

“Apparently he exhausted the poor man until he just wanted to cry uncle,” laughed English professor Maria DiBattista, who was close to Keeley and holds the endowed chair he once had.

Friends like DiBattista remember Keeley, who died at age 94, as courteous and kind with a terrific sense of humor — particularly when it came to self-deprecating jokes. His colleagues recall him as a lion in his fields — “the preeminent scholar and translator of modern Greek poetry of our time,” Dimitri Gondicas ’78, director of the Seeger Center for Hellenic Studies, wrote in a University remembrance.

“Many English-speakers were introduced to the riches of modern Greek poetry through his translations.”

Tom Papademetriou *01,

Modern Greek Studies Association President

Keeley was born in Damascus, Syria. His parents were Americans, his father a diplomat. He got to know Greece when his family lived in Thessaloniki and he attended the American Farm School. His time at Princeton was split by World War II when he signed up for a year in the Navy in 1945.

Later, as a doctoral student at Oxford, Keeley wrote his dissertation on two Greek poets, Seferis and C.P. Cavafy. That’s when he tracked down Seferis with help from “my spies” at the Greek Embassy in London, Keeley wrote in his 2005 memoir, Borderlines.

Keeley directed Princeton’s Program in Creative Writing from 1965 to 1981 and was a force behind the creation of the Seeger Center and the Modern Greek Studies Association in the U.S. “Many English-speakers were introduced to the riches of modern Greek poetry through his translations” — including of Seferis — in the 1960s and 1970s, association president Tom Papademetriou *01 wrote upon Keeley’s death.

In addition to his memoir, Keeley wrote a tall stack of books and poetry, including eight novels. From 1992 to 1994 he served as president of PEN America, a nonprofit that defends writers and freedom of expression.

DiBattista described Keeley as gallant, loyal, and tolerant of people’s foibles and politics — he’d talk with anyone who had a good heart. He also had deep convictions about the importance of the humanities in helping people develop the values and perspective they need in life.

“Every time I saw him interact with other people, there just was this very open, unpretentious, engaging personality that came out. He really was interested in other people,” she says. “He was just a remarkable person.”

Elisabeth H. Daugherty is PAW’s digital editor.

This story has been updated from its original version. Edmund Keeley graduated from Princeton in 1949 but was a member of the Class of ’48.

In this 2017 interview, Keeley discusses translation and PEN America:

1 Response

Madeleine Picciotto ’78 *85

2 Years AgoA Brilliant Teacher and Mentor

I was very saddened by the death of Edmund “Mike” Keeley ’48, a professor who was central to my Princeton experience. The memorial article published in the February issue (“Lives Lived & Lost”) ably recounts his significance as a translator of modern Greek poetry, as well as many of his other accomplishments. But it does not mention his brilliance as a teacher, and what a valuable mentor he was to young translators trying to master the difficult work of conveying a literary text into graceful English.

I enrolled in his translation workshop almost every semester that I was at Princeton, both as an undergraduate and a graduate student, and it was the most valuable educational experience I have ever had. Mike taught us that literary translation is a creative art well worth cultivating. He took us seriously, respected our often-halting attempts, helped us to find ways to express ourselves more effectively, supported us as we sought wider audiences for our work, and encouraged us to go farther than we ever thought we could — all with impressive patience and good humor. I regret that future students will not have the chance to experience this gift.