Lives: James Everett Ward ’48

One of Princeton’s First Black Students, He Found Connection in the Community

March 16, 1923 — May 27, 2022

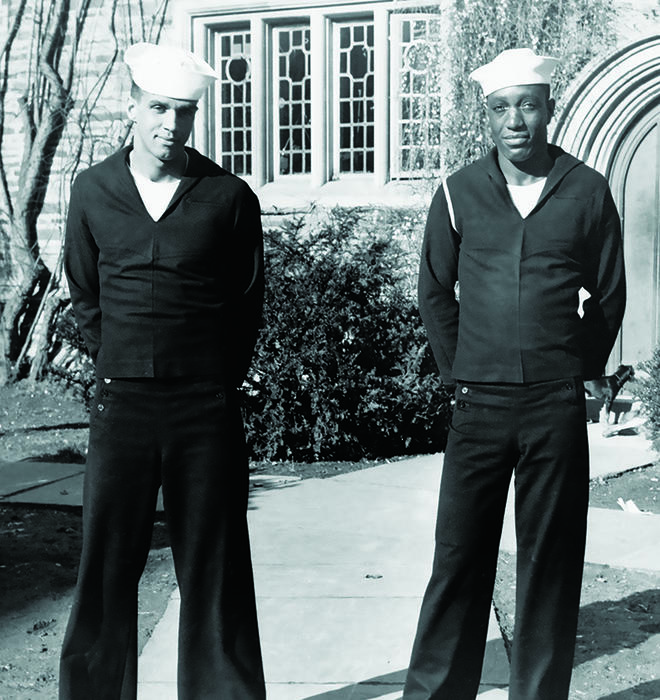

The two men facing the camera in the black-and-white photo appear confident and comfortable in their postures but somewhat uncertain in their facial expressions. Perhaps they are absorbing their surroundings and the circumstances that have brought them there. Dressed in dark Navy uniforms with white sailor caps, James Everett Ward ’48 and Arthur Jewell Wilson ’48 strike a sharp contrast to the collegiate ivy and archway of Laughlin Hall in the background, a distinction made even more apparent by the color of the men’s skin.

Ward and Wilson were among Princeton University’s first Black students, alongside John Leroy Howard ’47 and Melvin Murchison Jr. ’48. In 1939, the University effectively rescinded the admission of Bruce Wright h’01 on the day that he showed up to register for classes after seeing he was Black [Princeton Portrait, December 2022]. In a letter Wright received after he was sent home, the dean of admissions said that Princeton does not discriminate based on race, color, or creed but insisted that Wright “would be happier in an environment of others of his own race.”

Just a few years later, the environment for all students at the University would change drastically. With thousands of college-age men nationwide opting to enlist to fight in World War II, enrollment dropped at many colleges across the nation. For example, Princeton’s enrollment plummeted from 2,432 students in fall 1941 to fewer than 400 civilian students in July 1944. To fill the gap, these institutions embraced a new proposal from the U.S. Navy; to educate midshipmen for future leadership roles, the Navy created the V-12 Naval Training School, in effect sending thousands of its enlistees to college.

Because he came through the V-12 program, Ward — who died May 27, 2022 — was able to attend Princeton when civilian Black students most likely would have been denied admission.

“The Princeton experience

was a tremendous cultural experience, an exposure to an area of Americana that was completely foreign to me.”— James Everett Ward ’48

“These men, they were pioneers,” says David Steigman ’75, a retired commander with the U.S. Naval Reserve who has studied the integration of African Americans into the Navy. “They provided a source of light both to Princeton University and to the United States Navy.”

Steigman notes the academic success that Ward and his Black classmates achieved at the University. “None of them was thrown out of the V-12 program, which speaks both to their dedication, intelligence, and competence,” he says. “And [it] speaks to the Navy leadership at Princeton, because not everyone in every V-12 program in college succeeded.”

For Ward, who grew up in Oklahoma, “the Princeton experience was a tremendous cultural experience, an exposure to an area of Americana that was completely foreign to me,” he told his classmates in their 50th Reunions yearbook. In a 2007 letter to PAW, Ward said that the Black Witherspoon community, the historic neighborhood north of Nassau Street, played a significant role in helping him and the other Black students adapt to life on campus.

“With no request or solicitation, they opened their doors and hearts to four Navy V-12 students in an outpouring of friendship and hospitality that can only be imagined,” Ward wrote. “It was amazing how a community with no aspirations of becoming a part of the University student or faculty body had such a fierce love and loyalty to the University.”

According to Ward’s letter, the Black community in the town also helped him and his colleagues adjust to civilian status, another change the men underwent as the war ended while they were college students. Ward ultimately returned to live in McAlester, Oklahoma.

Despite the academic success of Ward and the other Black students in the V-12 program, Princeton would not enroll sizable numbers of Black students for two more decades.

Kenneth Terrell ’93 is a writer and editor for AARP magazine.

No responses yet