Sept. 10, 1931 – July 17, 2018

IN 1977, Lincoln Brower ’53 first visited the mountainside forests west of Mexico City where migrating monarch butterflies spend the winter. Millions of butterflies blanketed the oyamel fir trees, displaying the grayish undersides of their familiar orange-and-black wings. Brower stood in awe one morning as the temperature warmed and the monarchs began to take flight.

“It was like walking into Chartres Cathedral and seeing light coming through stained-glass windows,” he recalled in a 1997 interview with National Wildlife. “This was the eighth wonder of the world.”

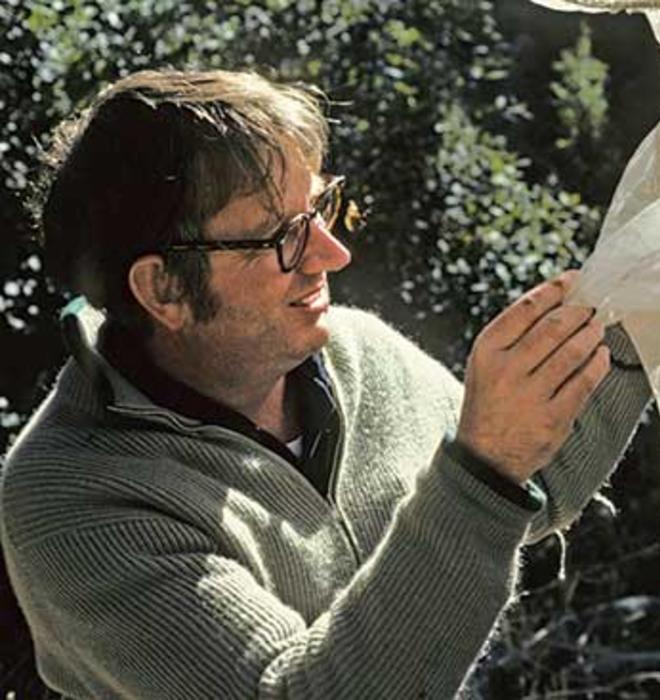

Brower, who died last July at age 86, devoted more than six decades to uncovering the secrets of monarchs and other insects. He also worked to protect the monarchs’ astounding migration, which spans thousands of miles, from threats such as deforestation, herbicides, ecotourism, and climate change.

“He was in his element anytime he was doing anything with the monarch butterfly,” says Linda Fink, Brower’s wife for the last 27 years and a colleague on the biology faculty at Sweet Briar College in Virginia. “He loved doing lab work, he loved talking to people about them, showing a little kid a milkweed with a caterpillar. He got great enjoyment out of every aspect of the work that he did.”

From an early age, Brower was fascinated by the insects he encountered on his family’s farm in Chatham, N.J. An aunt introduced young Lincoln to an amateur lepidopterist who lived nearby; the two would collect butterflies and moths in what is now the Great Swamp National Wildlife Refuge.

Brower once skipped his afternoon classes in high school to track down a particularly interesting green moth, Feralia jocosa, and landed an in-school suspension. “I learned from this early little act of civil disobedience that you have to rely on your own judgment as to what’s interesting in life,” Brower told a Vanity Fair reporter in 1999.

As a professor, Brower pursued wide-ranging and often inventive fieldwork, including studies co-authored with his first wife, Jane Van Zandt Brower. He explored adaptive coloration and mimicry in nature, the courtship of butterflies, and the toxicity of monarchs, which ingest chemicals from milkweed that make them indigestible for many bird predators.

He engaged audiences beyond the academy, sounding the alarm about threats to the monarch migration, which he called an “endangered biological phenomenon.” The overwintering sites in Mexico have shrunk dramatically due to illegal logging, and widespread agricultural use of the herbicide glyphosate (Roundup) has decimated the milkweed plants on which monarch caterpillars rely.

“He was very realistic about the situation and thought it was all unraveling right before his eyes,” says Elizabeth Howard, founder of the citizen-science website Journey North. “But he didn’t quit. He just kept at it, with great frustration, but kept at it nevertheless.”

In 2014, Brower joined three environmental nonprofits in petitioning for Endangered Species Act protection for the monarch population, which had declined by an estimated 90 percent. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is scheduled to make its decision later this year.

Even as the number of butterflies dwindled, Brower found some cause for optimism, pointing to the monarch’s remarkable reproductive capacity and its history of enduring natural traumas. “Like cockroaches, they’ve managed to survive for eons, through thick and thin, through asteroids and everything,” he told The Washington Post in 2013. “So the monarch has the chance of coming back fast. ... But I’m beginning to have doubts.”

Brett Tomlinson is PAW’s digital editor.

Watch: Lincoln Brower on ‘What Good Is the Monarch Butterfly?’

Lincoln Brower on What Good is a Butterfly from Dorothy Fadiman on Vimeo.

1 Response

Anne Pringle s’68

7 Years AgoA Special Journey with Lincoln Brower

Nine years ago, my husband (Harry Pringle ’68) and I took a Princeton Journeys trip to the sites in Mexico where the monarch butterfly overwinters after its migration south. Lincoln Brower ’53 (“Lives Lived and Lost,” cover stories, Feb. 6) was our guide.

Aside from all that we learned from Lincoln, we most remember his infectious enthusiasm as we climbed up to the first stand of oyamel fir trees, on which were hanging tens of thousands of monarchs. His palpable excitement was as though this was his very first visit, even though he had been dozens of times before. He was even more excited to show us the sex organs of the monarch and how they mate! From what he learned from Lincoln, Harry is now revered in our small community as a monarch expert and has even given lectures. Thank you, Lincoln, for a memorable experience and one with an afterlife. We think of you every time we see a monarch in our butterfly-friendly gardens.