Nov. 24, 1951 — Feb. 1, 2022

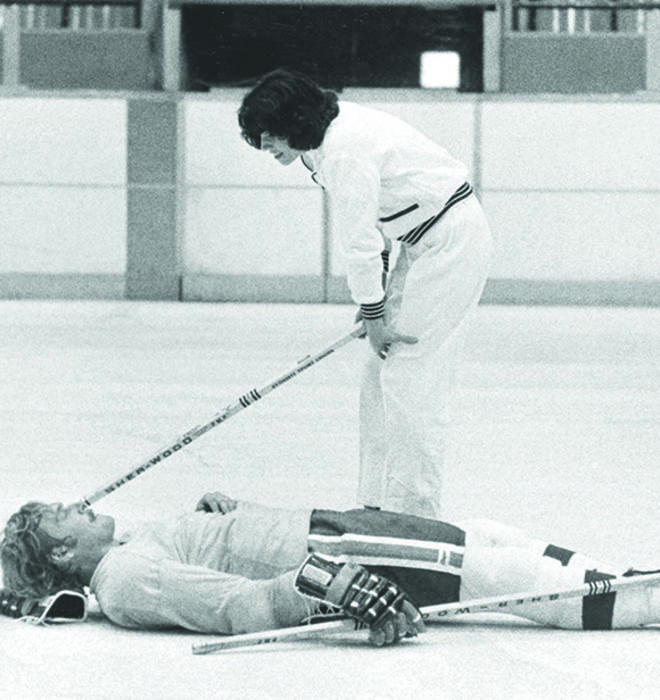

When Robin Herman ’73 entered the locker room following the 1975 National Hockey League All-Star game in Montreal, she quickly turned into the very thing journalists dread — the story.

Herman became the first full-time female sportswriter at The New York Times soon after graduating from Princeton. But when she began covering the New York Islanders in 1974, she was denied access to the team’s locker room, an inner sanctum where athletes tend to express their most authentic and controversial feelings in the rush of adrenaline that often follows hard-fought competition.

The locker room had also become a symbolic battlefield, with one side decrying the idea of a woman walking amongst men in the nude, while serious working journalists such as Herman felt that to do their jobs well, women needed the same access as their male colleagues.

“I was a New York Times reporter, but because of my gender, I wasn’t allowed to do my job,” she said in the 2013 ESPN documentary Let Them Wear Towels.

“The first thing that struck me was she was very confident,” said lifelong friend Lawrie Mifflin, who, as an NHL reporter for the New York Daily News, began working alongside Herman covering the New York Rangers. “She never presented herself as a fragile flower type. She was very confident, but not strident and not overbearing. Never hostile.”

Herman wrote in the Times how after coaches finally allowed her into the locker room for the 1975 All-Star game, someone yelled, “There’s a girl in the locker room!”

“She asked, ‘Why am I doing half the work of everyone here?’ She demanded a sports beat. She wasn’t that interested in sports at the time, but she was interested in pulling her weight and being treated equally.”

— Paul Horvitz, husband

It would take another 12 years before every NHL team allowed women into the locker room. Herman continued to receive hate mail from fans, while some players and coaches hurled curses at her face, full of the worst sort of words meant to demean women. But Herman never wavered and was never intimidated, according to Mifflin. “When I think of Robin, I have an image of her with a notebook in her hand scribbling furiously and listening to players talk after a game,” she says. “She was a very good, assiduous reporter. She had all her facts marshaled, always had everything organized. She knew all the players. She was always getting to know the people on her beat.”

Those who knew her best say Herman honed what she needed to be successful in those moments as a member of Princeton’s inaugural class of women. “By being in the first class, everyone at these previous male institutions had to develop a little bit of a thick skin and a lot of confidence,” says Mifflin, who is a member of Yale’s first class of women (1973). “Certainly, Robin had it and always handled it very gracefully.”

Born in 1951, Herman grew up on Long Island. “We were both kind of middle-class Jewish children with no Princeton legacy who like to write a lot,” says Gil Serota ’73, who spent four years working with Herman at The Daily Princetonian.

“Robin had no problem being friends with guys,” Serota says. “She just fit in with the men. She was super smart and ambitious, a sports fan, but humble and down-to-earth, and she made it easy, super easy, to get along with her.”

When Herman joined the college paper, every first-year at the Prince received a news beat and a sports beat. But senior editors who made the assignments assumed Herman didn’t want to cover sports. “She asked, ‘Why am I doing half the work of everyone here?’” her husband, Paul Horvitz, says. “She demanded a sports beat. She wasn’t that interested in sports at the time, but she was interested in pulling her weight and being treated equally.”

By their junior year, Herman and Serota became co-editors of the sports section. “One of the things we did that had never been done before was to call every varsity athlete and do an anonymous coaches poll to find out what they thought about the coaches,” Serota remembers. “It resulted in several coaching changes because there had been a lot of legacy coaches who had outlived their expertise.”

Herman transitioned from sports to the metropolitan desk in 1979, where she wrote one of the newspaper’s first stories on the AIDS epidemic in New York City, according to Horvitz, who met Herman when he was a national editor at the Times. They welcomed two children, Eva and Zachary, while working in Paris in the 1980s.

After stints as a health journalist at the International Herald Tribune and The Washington Post, Herman became the assistant dean of communications for the School of Public Health at Harvard University in 1999. “She got a chance to build it from nothing,” Horvitz says. “She realized she was surrounded by really smart, dedicated health-care and research professionals whose stories weren’t being told. She made it her business to tell their stories.

“She really loved, I mean loved, Princeton as an institution,” her husband says. “She was very proud of being in the first class of women. She was very glad to see women thrive there.”

Horvitz says it was Herman, along with a female classmate, who created the “Co-Education Begins” banner that leads the P-rade procession for the Class of 1973 each year. “At first it was a hand-drawn banner,” Horvitz recalls. “In the early years, there were a couple of instances where it was stolen and they had to keep remaking it. But now it’s considered sacrosanct and always gets big applause. The younger classes just love it.”

Herman spent seven years fighting ovarian cancer before dying in February at the age of 70. Even though sports writing accounted for just a few years of a varied and storied career, Herman told her husband she knew she would always be remembered as “the girl in the locker room.”

Tisha Thompson ’99 is a Peabody- and Emmy-award-winning investigative reporter for ESPN.

No responses yet