May 10, 1918 • March 13, 2018

THE PIONEERING WORK of T. Berry Brazelton ’40 in the field of developmental and behavioral pediatrics is perhaps best understood in terms of the norms he razed. Most pediatricians of the early 1950s believed that newborns arrived unable to feel pain or respond much to the world around them, and developmental deficiencies were almost always blamed on parenting. Brazelton instinctively bridled at these standards — in fact, he almost left pediatrics after his medical training. But out of financial need, Brazelton set up a private practice in Cambridge, Mass., unaware that he was beginning a career that would dismantle much of the era’s paradigm.

Children who were diagnosed with autism in the mid-20th century were thought to have been victims of substandard nurturing during infancy, which often meant placing the blame squarely on mothers. But Brazelton noticed that characteristics of his autistic patients were too similar to have been created by different moms.

He began observing newborns at a stage “before parents could really impact their children,” says Joshua Sparrow, the director of the T. Berry Brazelton Center, who co-authored several books with Brazelton. “What he found was that at birth, within the first hours of life, newborn babies are unique individuals.”

After decades of research, this premise evolved into the Brazelton Neonatal Behavioral Assessment Scale, which is widely used to assess a new baby’s responses to stimuli, such as turning her head toward a voice or following a ball with her eyes. The scale has contributed to the universal recognition of newborns as complex, self-directed individuals, and can help detect an infant’s weaknesses early on, which may lead to early medical intervention.

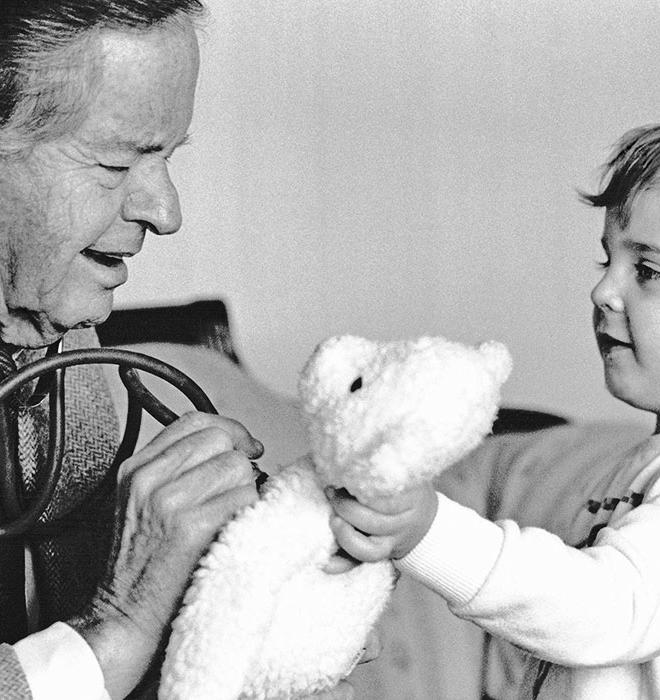

Over the course of his career — though no longer treating children, he was still mentoring others at the Touchpoints Center at age 99 — Brazelton, who was often called the “baby whisperer,” claimed to have seen some 25,000 patients. He credits parents for bringing him “nuggets” from their experiences, which formed the basis of his Touchpoints model of development, a pioneering theory that suggests that before each new developmental milestone, such as walking, comes a period of developmental regression. Brazelton’s series of Touchpoints books chart a child’s development, decoding behavior to reassure anxious parents.

Brazelton, who was born in Waco, Texas, had a Southern drawl and folksy mien that contributed to his rapport with patients and with a large cable-television audience for his weekly show, What Every Baby Knows, which ran from 1983 to 1995. But his demeanor was a liability among his colleagues at Harvard Medical School and Boston Children’s Hospital, where he held academic appointments. “In academic circles, if you’re charming and a good communicator, it is somehow imagined that you couldn’t possibly also be a rigorous scientific researcher. That was a challenge for him,” says Sparrow.

His charm played well in political circles: Brazelton served on President Bill Clinton’s Commission on Children, and he lobbied for family-leave policies and early childhood care in disadvantaged communities. In 2013, President Barack Obama awarded him a Presidential Citizens Medal.

Eldest daughter Kitty Brazelton recalls tagging along on one of her father’s many cross-cultural research trips to watch childbirth in a remote Mexican village. She was meant to translate for him, but “I quickly learned I was superfluous,” she says. “My dad was able to communicate as a human being across languages.”

Carrie Compton is an associate editor at PAW.

Watch: T. Berry Brazelton on the Roots of his Interest in Pediatrics

Courtesy WhiteHouse.gov

2 Responses

Marcia Gonzales-Kimbrough ’75

6 Years AgoLife Stories

When we adopted our daughter we had almost no information about her birth parents, her parents’ health histories, personalities, etc. We knew that her birth mother had been adopted, so she herself would not likely have known much about her own birth parents. We knew that our daughter might have learning disabilities later on due to poor prenatal care for her teenage birth mother.

Dr. T. Berry Brazelton ’40 was my guide to early-childhood parenting. Reading his book and watching his program on television helped me know more about how each child is an individual from birth. He helped me to better understand the developmental stages our daughter was progressing through. Especially helpful was understanding that at times she was not regressing but rather was at a touchpoint, heading into the next developmental stage. My daughter and I together had fun while watching Dr. Brazelton on television.

Although we would like to have known more about our daughter’s birth parents, we know that our daughter is a beautiful, loving, compassionate, and wise young woman who is fulfilling her highest potential. Parenting is the most important job we’ll ever have, and the job for which many of us feel the least trained to do well. Thank you to Dr. Brazelton for being my guide and helping hand.

Kathleen M. Scanlon

7 Years AgoA Refreshing Story

A most refreshing story, particularily in a medical era where not all doctors are intuitively dedicated to connecting and caring for the patient as "an individual." This story reminds me of a very special naturopath, Dr. Wayne C. Diamond, who also listened, observed, then rendered his human professional acumen to treat his patients most effectively .... and what a delightful opportunity for his daughter to witness her Dad's cumulative brilliance kinetically in Mexico !