Clarence King, a celebrated explorer, geologist, and surveyor in 19th-century America, chose to set that identity aside — and live as a working-class black man during a time of harsh racial segregation in the United States. He did it for love.

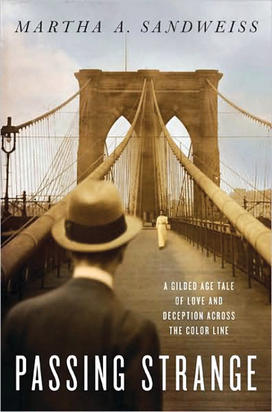

King moved back and forth between two sides of the color line: as the very public white, Newport-born, Yale-educated cartographer and researcher of the American West, and at other times as the strangely private man pretending to be a black Pullman train porter and itinerant steelworker (using the alias “James Todd”) who married an African-American woman. Martha Sandweiss, who joined Princeton’s history department this semester, explores King’s double life in her book Passing Strange: A Gilded Age Tale of Love and Deception Across the Color Line, published by Penguin Press in February.

“While racial passing was surely attempted by some light-skinned blacks who wanted to escape the economic disadvantages tied to black life at the time,” explains Sandweiss, “it was virtually unheard-of for whites to voluntarily choose to face social and economic discrimination and live as black people.” But after falling in love with a black nursemaid, Ada Copeland, in 1888, that is what Clarence King did for 13 years. His wife and their five children had no idea that he was, in fact, white, and that he was the famous Clarence King, until he confessed it on his deathbed in 1901.

Realizing that it was not only scandalous for his career, but also illegal in virtually every state at the time for a white man to marry a black woman, King concluded that his only option was to create a part-time, fictional identity as a black man. In her book, Sandweiss carefully lays out how he accomplished this act of subterfuge. He would live among whites for weeks or months at a time, while telling his wife (who lived in their modest, suburban Queens home with their children) that he was across the country working as a Pullman porter or steelworker. He actually was either out West conducting research, or a one-hour train ride away in Manhattan. Only one or two of his oldest white male friends knew and kept the secret.

Sandweiss, who is co-editor of the Oxford History of the American West and formerly was a longtime history and American studies professor at Amherst College, first read about Clarence King many years ago in a 1958 biography. But as she points out, only five pages of the book were devoted to his life with Copeland, and his racial passing remained uncovered. “Many historians and [white] admirers of King avoided exploring the race issue in an attempt to preserve King’s image as a 19th-century hero,” says Sandweiss.

Despite King’s white skin, blond hair, and blue eyes, he was easily embraced by the black community as a black man because “he gave them facts that suggested a black identity,” says Sandweiss. He defined himself as a Pullman railroad porter, a job that was held exclusively by light-complexioned black men. “Race is much more fluid than many of us think,” says Sandweiss. “King’s story showed me how arbitrary racial distinctions really are.”

Lawrence Otis Graham ’83 is the author of 14 nonfiction books, including The Senator and The Socialite.

No responses yet