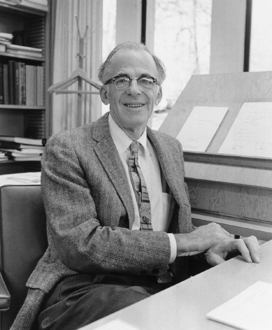

Lyman Spitzer Jr. *38 On Space

The following is an excerpt from Dr. Spitzer’s speech on Alumni Day.

It was in 1946 that the Air Force started to carry out a study of a satellite in orbit around the earth. Of course, your guess is as good as mine as to what the Air Force was going to use the satellite for, but a friend of mine who was associated with this study approached me one day and asked if I would be interested in participating in this study, to the extent of thinking about how such a satellite might be used in research in astronomy. Well, I’ve been a science-fiction fan for quite a few years, and I accepted with enthusiasm, and spent quite a little time thinking about just what one could do with a telescope several hundred miles above the atmosphere. This work convinced me that a large general-purpose observatory – a large telescope used for different types of observations above the atmosphere – would revolutionize astronomy. I still believe this to be the case.

Now, why do we wish to observe stars, or the heavens generally, from above the atmosphere? There are two reasons. In the first place, the atmosphere – the beautiful air that sustains life and surrounds our planet – bends light from a star in an irregular, transitory way. This produces the twinkling of the stars, a very romantic addition to the night sky, but of course, astronomers are a hard-headed lot, and it seems sort of a nuisance. As the light from the stars moves around through the air, it moves on a photographic film, and the picture gets blurred, producing somewhat the same effect you’d get in taking a time exposure of a baby engaged with its rattle.

The second reason for going out into space for astronomy is that the air absorbs light in the far ultraviolet, the far infrared, as well as X-rays and certain radio waves, with the result that if you want to look in these “dark octaves,” as they are sometimes called, you have to go above the atmosphere – go up several hundred miles – and observe the heavens from a space platform above the air.

When I came to Princeton in 1947, one of my major professional goals for the department was to encourage a general program in space research that might someday lead to a large telescope in orbit out in space, of the sort I’ve just described. And during the next few decades, we had a number of programs leading toward that goal. Roughly every ten years, we had a different type of telescope that we would launch, or NASA would launch, or that would somehow get up into space. The launch of the [Hubble] Space Telescope will be a fine climax for this series, although I must confess that it will not be in any sense a Princeton instrument.

This was originally published in the March 8, 1989 issue of PAW.

No responses yet