Many Abolitionists Fought on After the Civil War

Editor’s note: This story from 1968 contains dated language that is no longer used today. In the interest of keeping a historical record, it appears here as it was originally published.

James M. McPherson, A.B. Gustavus Adolphus College and Ph.D. Johns Hopkins, is Associate Professor of History at Princeton. He is the author of The Negro’s Civil War, The Struggle for Equality: Abolitionists and the Negro in the Civil War and Reconstruction. His articles include: “How U.S. Historians Falsified Slave Life” in University, Summer 1967. This essay stems from his current research on the evolution of American attitudes toward the Negro undertaken on a Guggenheim Fellowship and is adapted with permission from Towards a New Past: Dissenting Essays in American History, edited by B. J. Bernstein, Pantheon 1968. Copyright 1968 Random House, Inc.

Northern victory in the Civil War failed to bring about the lasting improvement in the lot of freed Negroes that liberals, or abolitionists, had hoped for. To what extent was this failure due to a change of heart — a retreat from full commitment to the foals of racial equality — on the part of the liberals?

Historians have tended to conclude that the southern Negro was largely abandoned by his pre-war Northern friends, but a perusal of the activities of many abolitionists during Reconstruction calls the traditional interpretation into question. Most of these reformers were active in behalf of equal civil and political rights for Negroes and worked to bring education and economic assistance to the freedmen in the 1860s. Even in the 1870s a majority of former abolitionists continued to insist on strict and expanded enforcement of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments.

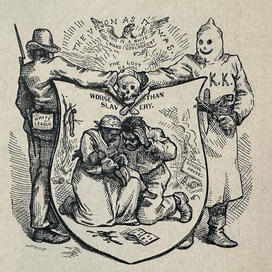

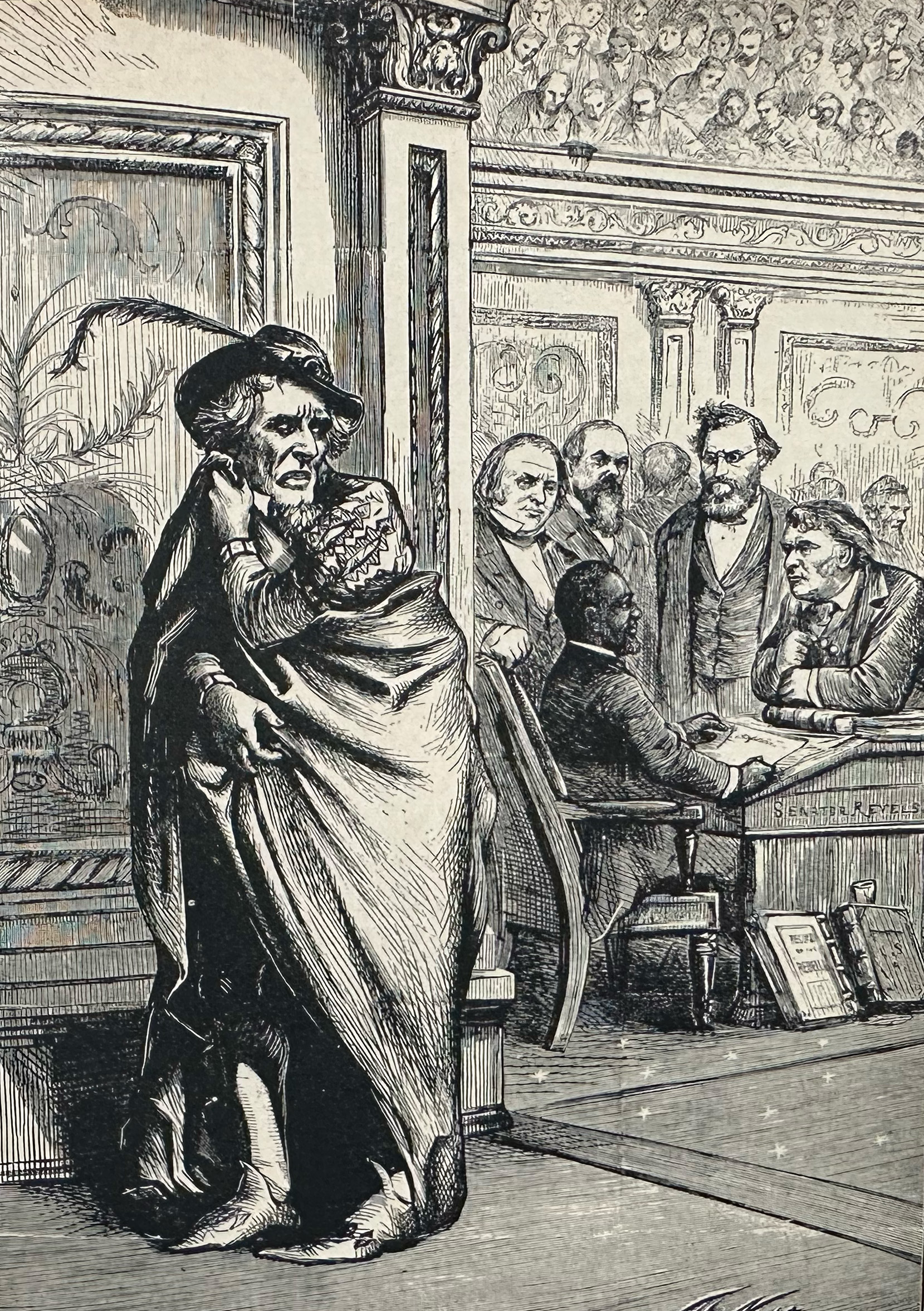

![1.jpg “Halt! This is not the way to ‘repress corruption and to initiate the Negroes into the ways of honest and orderly government.’” [1874]](/sites/default/files/styles/small_272/public/2024-11/1.jpg?itok=mA3FR1W9)

There has been no thorough study of the post-Reconstruction attitudes of former white abolitionists and their descendants toward the race problem, but this essay, based on an investigation of approximately 125 white abolitionists and their descendants, will set forth some tentative generalizations.

It will be wise to concede at the outset that the thesis concerning their “abandonment” of the Negro is partly correct. Nearly half of the abolitionists alive in the 1870s did become disillusioned to some degree with radical Reconstruction and approved or accepted the withdrawal of federal troops from the South in 1877. But their subsequent behavior cannot be summed up in the simple concepts of indifference or abandonment. Many of them remained committed to the equalitarian ideals of Reconstruction and active in efforts (chiefly educational) to fulfill these ideals. More than half opposed the cessation of Reconstruction and continued to demand federal enforcement of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments. And in the years after 1890, as disfranchisement and segregation made these amendments meaningless, some abolitionists and their descendants played key roles in a movement that led to the founding of the NAACP in 1909-1910.

Historians are familiar with the revulsion of Northern opinion toward Reconstruction in the 1870s. Widely publicized stories about the corruption and incompetence of “Negro-Carpetbag” governments produced a growing disgust that helped the Democrats win control of the House in the 1874 congressional elections. By mid-decade there were multiplying signs that influential Republican were prepared to jettison the party’s Southern policy as a political liability.

Many veterans of the antislavery crusade were alarmed by these developments. Vice-President Henry Wilson told William Lloyd Garrison in 1874: “I fear a Counter-Revolution. Men are beginning to hint at changing the condition of the negro.” The old abolitionists, said Wilson, “must call the battle roll anew, and arrest the reactionary movements.” Garrison admonished a reunion convention of abolitionists to “beware of the sire-cry of ‘conciliation’ when it means humoring the old dragon spirit of slavery and perpetuating caste distinctions by law. … We shall still show ourselves to be the truest friends [of the South] by refusing to compromise any of the principles of justice as pertaining to her colored population.”

In 1875 a group of Boston citizens held a meeting in Faneuil Hall to denounce the use of federal troops to uphold Republican control of Louisiana. Wendell Phillips appeared at the meeting and declared that the freedmen would be abandoned to the fury of unreconstructed whites if federal protection was withdrawn.

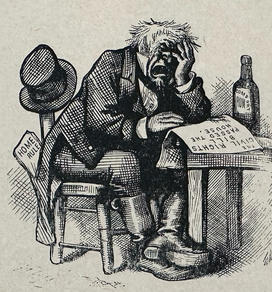

![3.jpg Nast celebrated President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation with drawings showing the happy, productive life ahead for freedmen in the South: a premature celebration, as it turned out. [1863]](/sites/default/files/styles/small_272/public/2024-11/3.jpg?itok=cbZ6z5na)

“When the negro looks around on the State government about him and sees no protection,” said Phillips, “has he not a full right, an emphatic right, to say to the National Government at Washington, ‘Find a way to protect me, for I am a citizen of the United States’?” Phillips would consider himself “wanting in my duty as an old Abolitionist [loud hissing and applause, reported the Boston Journal] if I did not do everything in my power…to prevent a word going out from this hall that will make a negro or a white Republican more exposed to danger and more defenseless.”

In 1877 President Rutherford B. Hayes withdrew the last federal troops from the South. Phillips, Garrison, and many of their old abolitionist allies protested against what they considered this betrayal of the freedmen. Phillips had little faith in the pledges of Wade Hampton and other Southern leaders to respect and uphold the equal rights of Negroes, saying “To trust a Southern promise would be fair evidence of insanity.”

Hayes and his supporters defended the administration’s policy on the grounds that disorder and violence had ceased in the South since the troops were withdrawn. But Garrison wrote in 1878, “We are complacently told that this wonderful ‘policy’ has brought quietude to South Carolina and Louisiana, the shot-gun is laid aside, and blood no longer flows. Well, ‘order reigns in Warsaw,’ but where is Poland? … The colored people of those States have, by this process, been thoroughly ‘bull-dozes’; their spirits are broken, their hopes blasted, their means of defense wrested from them: what need of killing or hunting them any longer? And is this awful state of things to be held up as something worthy of congratulation?”

Garrison never changed his mind about Hayes’s policy, and shortly before his death he uttered a final rallying cry to the dwindling antislavery hosts in a letter to Phillips: “while the freedmen at the South are, on ‘the Mississippi plan,’ ruthlessly deprived of their rights as American citizens, and no protection is extended them by the Federal Government…the old anti-slavery issue is still the paramount issue before the country.”

But the country wanted nothing more to do with “the old antislavery issue.” The New York Times on June 1, 1876, said, “Wendell Phillips and William Lloyd Garrison are not exactly extinct forces in American politics, but they represent ideas in regard to the South which the great majority of the Republican party have outgrown.” Approximately 55 to 60 percent of the one-time abolitionists still alive joined Phillips and Garrison in deploring the abandonment of Reconstruction, but their voices fell on increasingly deaf ears.

Garrison died in 1879 and Phillips in 1884, but a handful of their followers tried to carry on the old traditions. In 1886 Norwood P. Hallowell, an abolitionist who had commanded Negro soldiers during the war, spoke to a reunion gathering of his regiment. Hallowell praised John Brown and Robert Gould Shaw, another commander of black troops, who had died at the head of his regiment, as the greatest men of the Civil War era. “They did not die in vain,” he told the colored veterans. “See to it that we whose good fortune it has been…to survive the casualties of war, do not live in vain.” Negroes were still the victims of injustice in both North and South, said Hallowell, and so long as this was true “there is work to be done by those who revere the lives of John Brown and of Colonel Shaw.” Two years later Norwood’s brother, Richard P. Hallowell, writing to Garrison, said that “protection of the colored people in their political rights as guaranteed by the Constitution” should be the most important issue before the country.

At times it appeared that the Republican party agreed with Hallowell. Republican orators often waved the bloody shirt in the 1880s, and talked with seeming conviction about the need to protect Negro rights in the South. But this was little more than rhetoric. The federal government made no real effort to intervene in “Southern affairs” after 1877.

What of the 40 to 45 percent of northern liberals who did sanction the withdrawal of troops? Did their attitude constitute a desertion of the Negro? What were the reasons for their apparent change of mind toward the race problem in the South? The answers to these questions are complex, and they can perhaps best be approached by examining the statements of some of the most prominent antislavery spokesmen for Hayes’s policy. These people were more influential than the former abolitionists who denounced the abandonment of Reconstruction, partly because their ideas were in closer accord with Northern opinion by the mid-1870s, and partly because several of them were editors of powerful periodicals or newspapers.

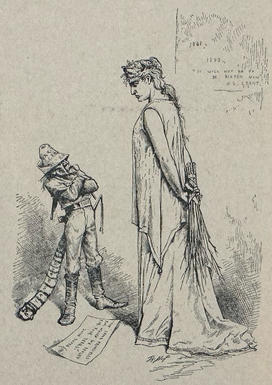

![3a.jpg “The color line still exists in this case” [1879]](/sites/default/files/styles/small_272/public/2024-11/3a.jpg?itok=CVEiXoYS)

The Nation, founded in 1865, effectively supported radical Reconstruction in its early years, but by 1870 this famous weekly had become an outspoken critic of Republican policies in the South. The Nation was largely abolitionist in its origins. George L. Stearns, Richard P. Hallowell, and J. Miller McKim raised most of the capital to launch the paper, which they hoped to make an organ for the cause of Negro rights and freedmen’s education.

When the first issue appeared in July 1865, Garrison gave his blessing to the Nation as the successor of the Liberator. One of Garrison’s own sons, Wendell Phillips Garrison, was assistant editor of the Nation from 1865 to 1881 and editor from 1881 to 1906. The British-born Edwin L. Godkin, who had come to America in 1856, was selected as editor. Godkin had not been an abolitionist, but during the Civil War he was a staunch advocate of emancipation and the Republican party, and he was accepted as editor by George L. Stearns and Wendell Phillips after they had quizzed him at length about his attitudes toward Reconstruction and the Negro.

Although Godkin may have appeared liberal on racial and social issues in 1865, his underlying conservatism and elitism soon emerged. He molded the Nation into an influential mouthpiece for the Brahmin elite of the Northeast, men of Mugwump outlook who were disgusted by the materialistic, get-rich-quick climate of the postwar period and its accompanying political corruption and crass ethics. Godkin quickly revealed an antipathy also to social reformers including some abolitionists, whom he occasionally derided as “sentimentalist” (analogous to today’s “bleeding heart liberals”). Almost the only “reform” he approved of was civil service reform, which would take the administration of public affairs out of politics and put it in the hands of intelligent people like himself.

This framework of attitudes soon produced disillusionment with Republican state governments in the South. In the early 1870s the Nation declared that some Southern governments were “an offence against civilization” run by “vulgar and rapacious rogues who rob and rule a people helpless and utterly exhausted.” At first Godkin directed most of his venom against the “carpetbaggers” and “scalawags,” but increasingly he placed the blame for Southern misgovernment on the freedmen.

In 1873 the Nation said of Negro voters in South Carolina that as “regards the right performance of a voter’s duty [they] are as ignorant as a horse or a sheep.” Godkin began to hint that the enactment of universal Negro suffrage had been a mistake: “After [seven] years’ experience of the working of negro suffrage at the South,” he wrote in 1874, “we…regret…that the admission of the negroes to the franchise was not made gradual, and through an educational test.”

In 1876 the Nation concluded that Reconstruction was a failure because it had undertaken “the insane task of making newly-emancipated field-hands, led by barbers and barkeepers, fancy they knew as much about government, and were as capable of administering it, as the whites.” Naturally the Nation approved of Hayes’s withdrawal of federal troops from the South, and predicted that “the negro will disappear from the field of national politics. … As a ‘ward of the nation’ he can non longer be singled out for especial guardianship.” This from a periodical founded expressly to uphold equal rights!

Of course, many of the abolitionist founders of the weekly considered themselves betrayed by Godkin, withdrew their support and capital from the Nation, and denounced it bitterly. But others, though they sometimes thought Godkin extreme in his statements, nevertheless continued their connection with the paper.

For 35 years Godkin’s steady associate on the Nation, Wendell Phillips Garrison, provided an interesting example of the transformation of a radical. From 1863 to 1865 young Garrison had written many articles and editorials for the Liberator and Independent advocating a “thorough” reconstruction of the South, including Negro suffrage and land reform, and had censured Lincoln for his cautious policies. Wendell was actually more radical than his father in these years. But after he joined the Nation in 1865, young Garrison came under the influence of Godkin’s personality, and was soon parroting Godkin’s mugwumpery, his elitism, and his disenchantment with Reconstruction.

This led to some sharp exchanges between Wendell and his father, who had become a bitter critic of the Nation. In 1874 Wendell told his family that since the freedmen’s “rights are now constitutionally assured, it will be no harm if they drop back…and refrain from taking a leading part in politics. They need more than anything else to have the gospel of education, thrift, industry, and chastity preached to them.” A month later, after a particularly strong anti-Reconstruction editorial in the Nation, William Lloyd Garrison complained to his son of the Nation’s “lack of sympathy with and evident contempt for the colored race. In all these respects it manifestly grows worse and worse, and utterly at variance with the hopes and expectations of those who took a special interest in its success at the outset.”

Wendell’s reply indicates how far he had departed from the faith of his father: “It is useless for you and me to exchange arguments on this matter. You see in every Southern issue a race issue, and your sympathies are naturally with the (nominally) weaker side.” Wendell, on the other hand, believed that in the South and everywhere else “good government is first to be thought of and striven for, and that the incidental loss that it may seem to occasion to either race is far less mischievous than the incidental protection accorded to either by bad government.”

Other journalists with an anti-slavery background also became disillusioned with Reconstruction in the 1870s, though none went so far as the Nation. Another prominent civil service reformer who, like Godkin, thought the “best people” should rule, and who was eventually convinced that the best people in the South were whites of the upper and middle classes, was George William Curtis, editor of Harper’s Weekly from 1863 until his death in 1892. Curtis had never officially joined an antislavery society, but he married the daughter abolitionists and by the 1850s he was committed to the full range of abolitionist objectives. He was a militant racial equalitarian in the 1860s, and his editorials in the powerful Harper’s Weekly (which averaged a circulation of nearly 150,000 during the Civil War and Reconstruction) were influential in the struggle for Negro rights.

Long after many Northern intellectuals had become disenchanted with Reconstruction, Curtis still insisted that equal rights in the South must be upheld by federal power. “This is the very time to insist that the policy which has been adopted shall not be abandoned,” he wrote in 1874. “No intelligent observer can doubt that [a restoration of white Democrats to power] would lead to a policy of oppression toward the colored race.” But by 1875 Curtis had begun to change his mind. The Fourteenths and Fifteenth Amendments, he declared, “do not change the national administration into a ‘paternal government.’ … Even when all citizens are made equal before the law… a great deal of injustice, disorder, and outrage will still remain… [It] is not wise to expect the national power to do by force of arms what can be done only by moral processes and by time.”

In 1877 Curtis, after some hesitation, approved of Hayes’s withdrawal of troops from the South. After all, he explained in Harper’s Weekly, a policy of force had just not worked. All but two Southern states had been lost to the Democrats under that policy. Negro voters had been the targets of greater violence in states where federal troops had intervened than in states free from outside interference. Strong-arm tactics may have been necessary at first in the postwar South, said Curtis, but in the end they succeeded only in keeping a few power-hungry corruptionists in office. Efforts to enlist the friendship, loyalty, and cooperation of moderate Southern whites would in the long run provide better protection for the freedmen than the stationing of a few hundred bluecoats in Southern cities. The old policy of “hate and hostility” was bankrupt; it was time to try a new policy of conciliation and cooperation.

Like Harper’s Weekly, the Independent supported radical Reconstruction until about 1874, and then gradually retreated to an attitude of compromise that led to approval of Hayes’s policy in 1877. The Independent had been founded in 1848 by Henry Bowen as a spokesman for the antislavery sentiment of the Congregational Church. Bowen was the son-in-law of Lewis Tappan, a prominent abolitionists, and a confirmed though sometimes cautious abolitionist in his own right. As owner and editor of the Independent from 1871 until his death in 1896, Bowen proudly and repeatedly affirmed the abolitionist lineage of the paper.

In 1874, amidst a growing outcry that Negro suffrage had proven a failure, the Independent denied that such a harsh judgment could be rendered after so short a time. “The negro, as a class, is entitled to patience and charity — or, rather, justice — at the hands of his Northern friends,” declared the paper. “He is the victim still of three centuries of the white man’s enforced degradation. How can he be expected to rise above it all in ten years? Give him a hundred, and then call him to account. Of the complete success finally of the experiment of negro suffrage, even in South Carolina, we do not entertain a doubt.”

The Independent also insisted that the federal government must protect Negro rights with utmost vigor. Referring to the White Leagues in Louisiana, the paper demanded: “Crush them, utterly, remorselessly. They are Ku-klux under another name…They are banded outlaws, sworn by intimidation, violence, or death to drive the negro from the polls and to restore white rule…Crush them!”

But 1874 was something of a turning point in the Independent’s attitude toward Reconstruction. While calling for charity — or justice — in judging the performance of Negroes, the paper itself sometimes betrayed a lack of charity. The stories of misgovernment, corruption, and outrageous conduct by Negro politicians in South Carolina caused the Independent to lament that “our colored fellow-citizens of South Carolina must do much better than they have done since [1867], or they will stagger the faith and disappoint the hopes of their true friends.” And not long after it had called for unremitting force to “crush” Southern oppressors of freedmen, the Independent abruptly proclaimed that “Congress should discontinue the system of special legislation in respect to the Southern States. The difficulties of the social problem in Southern society must mainly be disposed of by Southern society itself, and not by any outside power coming from Washington.”

Like several other abolitionists, Bowen had concluded that the race problem was more complex and difficult than it had appeared in the exciting, optimistic days of the 1860s. Constitutional amendments and legislation now seemed of limited avail in the face of Southern reality, and federal efforts at enforcement under President Grant seemed to worsen rather than help the situation. When Hayes inaugurated his policy of conciliation and good will toward the white South in 1877 the Independent, after a good deal of soul-searching, finally came out in favor of the policy. There seemed to be no viable alternative; the policy of the Grant administration had broken down, and the Hayes program at least gave some hope of a gradual, evolutionary improvement in race relations. Wade Hampton, L. Q. C. Lamar, and other leaders of the “better class” of Southern whites seemed well disposed toward the Negro and had promised that his rights would be protected.

Negro statesmanship had been less than a striking success, said the Independent in 1877, and the freedmen needed more education, experience, and religious uplift before they could take their rightful place as equals beside the white race. In the matter of Reconstruction “we are passing from the era of force to the era of slow education.” Force had failed, and “the question we ask, with no little anxiety is: Will religion and education solve the problem? Can they give us, at last, allowing them time enough, equality of political and social rights at the South? They must, for it is our only hope.”

This emphasis on time and education was a keynote in the thinking of many former abolitionists in the 1870s and 1880s. The impact of Darwinism on social thought was one cause of a transformation from immediatism to gradualism in theories of racial progress. The abolitionist movement had grown out of a complex interplay of intellectual, moral, and religious forces, including the Enlightenment’s concept of natural rights, Transcendentalism’s notion that human beings were basically good and capable of boundless betterment, and evangelical Christianity’s belief in the immediate expiation of individual and social sins by conversion to God’s truth.

The reform and utopian movements of the 1830s and 1840s, with their emphasis on immediate social change produced by the purposeful action of men working in harmony with God’s will, had formed the ideological substructure of abolitionism. The elements of immediatism in racial change envisaged by radical Reconstruction were, in part, products of this ideology. But by the 1870s many thinkers were beginning to apply the Darwinian concepts of biological evolution to social problems. Social change, they argued, could not be effected overnight by the conscious agency of man, but could develop only gradually, over a period of many generations, through the operation of natural forces beyond the control of man.

The effect of Darwinism on the social thought of some former abolitionists was exemplified by Abram W. Stevens, who had been converted to abolitionism as a young man in the 1850s. For twenty years Stevens was a radical reformer, hoping that his efforts would help cleanse America of sin and evil. The Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments had seemed to herald the dawn of racial equality. But by 1875 the impact of Darwinism plus the failure of Reconstruction to achieve the millennium had caused Stevens to change his mind.

Emotionally he still shared the hope that “a messiah and a millennium are sure to come, whereby and wherein every evil will be changed to good.” But intellectually he now rejected this hope. “It seems to me,” Stevens wrote, “that the great gospel of the nineteenth century is the discovery of Evolution,” and one of the main lessons of Darwin’s (and Herbert Spencer’s) revelation was that “all our efforts at reform, all our struggle and striving, are for naught… We see that everything does not depend upon us alone, to make society what it should be, — that Nature works even while we are asleep.” Once we learn the lesson of evolution “we become, not content with evil, but patient with it.” Social change “that is hastened or brought about by violent means is, so far as true progress is concerned, a stumble, not a step. It may be questioned if even the antislavery reform were not at last consummated too precipitately; if a more gradual emancipation, including a preparatory education for freedom, might not have been better.”

Darwinism did not teach, said Stevens, that man should sit back and let Nature do all the work. But man’s efforts should be those that work with evolution, not those that try to hurry it up, transcend it, bypass it. Education and the gradual amelioration of mitigable wrongs were the best means of working with Nature.” In formation rather than re-formation is my faith,” concluded Stevens. “And for this work the ‘eternal years of God’ are needed; and all ‘evils’ incident to its gradual accomplishment we must be patient and brave to endure.”

Few other former abolitionists articulated Darwinist ideas so clearly as Stevens, but several of them were influenced directly or indirectly by the new Darwinian intellectual climate. James Russell Lowell, erstwhile poet and essayist of the antislavery movement, said in 1876 that radical Reconstruction had been based on the mistaken assumption, which he had once shared, that “human nature is as clay in the hands of a potter instead of being, as it is, the result of a long past & only to be reshaped by the slow influences of an equally long future.” One of the first and most faithful of the Garrisonian abolitionists, Oliver Johnson, declared in an 1877 editorial approving Hayes’s Southern policy that “neither laws nor bayonets can remove the prejudices of race and social condition. For this time and patience are indispensable.” Many abolitionists from religious backgrounds also turned toward gradualism, contending that the Lord was on the side of racial progress but that “His forces are slow forces…To us the way may seem a slow one; but it is the sure one.”

For some erstwhile abolitionists, facile references to education and “the healing influence of time” no doubt served as rationalizations for a growing indifference to Negro rights. But for others, these concepts had genuine meaning and applicability. The abolitionists active in educational and religious missions to the freedmen did not believe that approval of Hayes’s Southern policy necessarily constituted an abandonment of the Negro. “Our work,” wrote one of them, “is more fundamental and important than that of either Congresses or courts.” The “only safeguard” of the freedman’s rights was “in his fitness to exercise and his ability to maintain them.” Only through education and the development of Christian character could this fitness be attained: “Intelligence and virtue are the…two great pillars of the porch of American citizenship and liberty. While it rests on anything else, it is uncertain and unsafe.”

Several prominent Negroes concurred in this shift of emphasis from agitation and protest to education and uplift in the 1870s. John Mercer Langston, a Negro abolitionist, lawyer, and one-time dean of Howard University Law School, praised the motives of “earnest and tried friends of the colored people” such as Garrison and Phillips who had denounced Hayes’s withdrawal of troops from the South as a sellout of the freedmen. But Langston warmly approved Hayes’s policy, and stated that the best way for the Negro to “become self-reliant and self-supporting” was through education plus economic and political “reconciliation” with Southern whites. George T. Downing, a Negro businessman and formerly a militant equalitarian, sanctioned Hayes’s policy and declared that the Negro race “will have to bide its time, get means, apply itself, struggle hard, become educated and skilled more in the science of government than fourteen years of freedom admits of.”

There has always been a tension in American Negro thought between protest and accommodation. In the two decades after Reconstruction the accommodationist viewpoint, with its accompanying emphasis on helf-help, education, and uplift, gained considerable strength in the Negro community, paving the way for Booker T. Washington’s enunciation of the Atlanta Compromise in 1895. The tension among Negro leaders was paralleled by a similar tension between the old agitation-immediatist tradition and the new emphasis on time and education among former white abolitionists. Most of the Negros and whites who stressed education, uplift, and gradualism did not believe they were “abandoning” the cause of equal rights; rather they looked upon their efforts as the only avenue by which the Negro could in the long run attain the character and ability to render these rights real and meaningful.

Throughout American history, education has been considered an important remedy for social ills, and the faith in the schoolhouse as an instrument of racial progress after the Civil War fit comfortably into this tradition. Former abolitionists did more than talk about education for the Negro. During and after the Civil War dozens of freedmen’s aid societies, most of them organized by abolitionists, set up hundreds of schools for emancipated slaves. Thousands of abolitionists and their sons and daughters went into the South to teach the freedmen.

Many of the education societies had dissolved by the early 1870s but several of the larger associations, sustained by Northern churches, continued their work for many decades: the American Missionary Association, the Freedmen’s Aid Society of the Methodist Episcopal Church, the Baptist Home Mission Society, the Friends’ Freedmen’s Relief Association, and others. These organizations has been founded largely by abolitionists within the various denominations, and their work was carried on after the war in substantial measure by men and women of antislavery background.

The American Missionary Association and the Methodist and Baptist societies supported scores of academies and normal school for Negro teachers and founded or lent support to several institutions that became the leading Negro colleges of the South: Atlanta, Fisk, and Howard Universityies; Berea, Tougaloo, Talladega, Morehouse, and Spelman Colleges; Meharry Medical School, Hampton Institute, and others. Many abolitionists were on the faculties of these schools, and former abolitionists of their descendants served as presidents of Howard University from 1877 to 1889, of Atlanta University from 1867 to 1922, of Berea College from 1869 to 1920, of Fisk University from 1875 to 1900, and of several other institutions during this period.

Living and working among the freedmen and witnessing at first hand their foibles as well as their virtues, some of these educators were among the earliest abolitionists to shift emphasis from equalitarian agitation and legislation to education and uplift. The American Missionary Association declared in 185 that constitutional amendments and statute laws had destroyed the “superstructure” of slavery but had left the “foundation” untouched — the “antagonism of races, the ignorance of the blacks, and the prejudices of the whites” which were “embedded in the minds and hearts of men” and “can only be overcome by education.”

In 1877 Richard Rust, an abolitionist of long standing who was executive secretary of the Freedman’s Aid Society of the Methodist Episcopal Church, wrote that emancipation and Reconstruction had not freed the Negro from the bondage of “ignorance and degradation” imposed by slavery. It was impossible to expect a people worn down by “centuries of heathenism and oppression” to “come forth clothed with all the qualifications of citizenship. Christian education, the development of heart and intellect…the education which our schools impart, is the only hope of this unfortunate people. Nothing else can free it from the disabilities of the past, protect it from the perils of the present, and prepare it for the mission of the future.”

This emphasis on “preparation” of the freedmen for the rights and responsibilities of citizenship led some abolitionist educators to anticipate the gradualism of Booker T. Washington. And the necessity of avoiding direct or provocative confrontation with the prejudices and power structure of the white South if their institutions were to survive caused others to anticipate Washington’s reluctance to speak out boldly against discrimination. But most of them never lost sight of their ultimate goal of first-class citizenship for the Negro, and some were surprisingly outspoken in their criticism of Southern mores.

Though the teachers of the freedmen were often narrowly moralistic, excessively pious, or offensive in their racial paternalism, they were nevertheless in some respects the real heroes of their age. The unquenchable religious faith and deep-rooted abolitionists convictions of many gave them the strength to persist in the face of Southern white hostility, Northern indifference, personal hardship, and countless disappointments in their work. Their belief in education as the chief remedy for the race problem may have been misplaced, but their contributions to racial progress were considerable and constituted perhaps the most enduring legacy of the antislavery movement.

A major objective of Hayes’s (and of his Republican successors’) Southern policy was to encourage the development of a two-part system in the South by taking the race issue out of sectional politics, thereby removing the outside pressure that had forced nearly all Southern whites into the Democratic party. Hayes hoped that once the color line was removed from politics both parties would appeal to the Negro vote, thus creating the circumstances in which Southern promises to respect freedmen’s rights could be fulfilled. Several former abolitionists were optimistic that Hayes’s program would serve the best interests of the Negro in the long run, and in the late 1870s and 1880s they discerned signs that the “let-alone” policy toward the South was really working.

In 1878 Thomas Wentworth Higginson took a trip through the South Atlantic states to observe conditions and visit some of the veterans of the Negro regiment he had commanded in the Civil War. Higginson, who professed to view the South with “the eyes of a tolerably suspicious abolitionists,” claimed that he found plenty of evidence of Negro prosperity and advancement under the Hayes policy. Wade Hampton’s promises in South Carolina were being carried out, Negroes continued to vote and hold office in the state, and there were few signs of a reaction in the direction of wholesale disfranchisement. Most of the soldiers from his old regiment, said Higginson, “agreed that wherever the Democratic party itself began to divide on internal or local questions, each wing was ready to conciliate and consequently defend the colored vote, for its own interest, just as Northern politicians conciliate the Irish vote, even while they denounce it.”

In the late 1870s and early 1880s the Democratic party in several Southern states split into factions, with one faction sometimes forming a coalition with the Republicans or with the Negro vote. In Virginia the “Readjusters” under the leadership of William Mahone controlled the state government for several years with Republican support. The Boston Transcript (edited from 1875 to 1906 by sons of Massachusetts abolitionists) declared in 1880 that the independent movements in Virginia and elsewhere “are pretty good evidence of the continuing and increasing disintegration of the solid South.” Mahone’s party was accomplishing “the wiping out of class and race distinctions, and placing Virginia alongside of Massachusetts in a national sense.” In 1885 the Nation states that “the lively bidding for Negro votes by the rival white parties in the recent contest over prohibition in Atlanta is only one of a number of signs that the color line in politics is vanishing throughout the South.”

The “New South” ideology of social and political regeneration through industrial progress captured the imagination of some Northern liberals, who believed that economic modernization of the South would improve the condition of both races and soften the racial animosities associated with an agrarian past and slavery. The Boston Transcript rejoiced that the South was becoming a “peaceful, law-respecting, industrious” section. “Work and money have brought into vogue new ideals, new tests and new ambitions in Southern society. Capital is, after all, the greatest agent of civilization…Money is the great emollient for social abrasions, and the two races…will move kindly together when wealth is more evenly divided between them.”

To bolster these optimistic conclusions the editors of the Transcript and others of similar outlook publicized every shred of evidence that seemed to illustrate progress in race relations. The Transcript noted that the Republicans polled 41 ½ percent of the majority party vote in the former Slave States in the presidential election of 1884, a gain of nearly 1 ½ percent over 1880. In 1888 the Republican vote slipped back to 40 percent, but Benjamin Harrison nearly carried Virginia and West Virginia; the Republicans did well in other border states, and elected several Southern congressmen. The Republican part, declared the Transcript in 1888, was becoming “a power in the South by enlisting intelligent leadership there and so dividing the colored vote, thus doing away with is suppression in a natural manner without force from the outside.” Wendell Phillips Garrison in an 1888 letter conceded that Negroes were often deprived of political power by various subterfuges, btu said they still had the legal rights granted during Reconstruction “and the nominal preservation of the suffrage is rapidly turning to real, and will in time enable them to take a hand in redressing the wrongs of legislation which yet remain…The colored people have Hayes to thank for the happiest years of their lives since emancipation.”

Much of this was probably wishful thinking subconsciously calculated to assuage bad consciences about the Compromise of 1877. But there was some truth in the notion that in the 1880s the Negro’s condition, though not ideal, at least gave promise of a gradual broadening of rights and opportunities. C. Vann Woodward and others have shown that Negroes continued to vote and hold office in substantial numbers in the 1880s, that rigid codification of Jim Crow practices had not yet taken place, and that not all the doors to better race relations in the South had yet been closed. The situation during the decade after Reconstruction was better in some respects than the decade of Reconstruction with its turmoil, violence, hatred, and race conflicts of which the Negro was the chief victim.

But events after 1890 eroded whatever basis for confidence had existed earlier. The decade of the 1890s produced a severe economic depression and a greater degree of social tension than ever before in American history. Political upheaval, the Populist movement, labor violence, jingoism, nativism, and a deterioration in race relations were some of the manifestations of this tension. The early 1890s saw an increase in the lynching rate; after 1892 the annual number of lynchings gradually declined, but the percentage of lynchmob victims who were Negro rose sharply. Moreover, the lynching of Negroes was increasingly accompanied by sadism and torture and accomplished by burning at the stake. Lynching bees frequently became the occasion for a holiday, with thousands watching the saturnalia of mutilation, torture, and burning flesh.

In the two decades after 1890 the Southern states disfranchised all but a handful of Negro voters by means of poll taxes, white primaries, and literacy or property qualifications that were enforced against Negroes but not against whites. During the same years the Southern states also enacted a host of Jim Crow laws that segregated the Negro in virtually every aspect of public life.

The conservative leaders of the South, the “Redeemers” who had ruled their states since the 1870s and who retained some of the paternalistic attitudes of slavery toward the Negro, were replaced after 1890 by a new breed of Southern politicians, the Ben Tillmans and James Vardamans and Jeff Davises who represented the “redneck” voters and whose chief stock in trade was often a virulent racism. At the same time the growth of scientific racism and the cult of Anglo-Saxon supremacy, the advent of imperialism, and the beginnings of the northward migration of Negroes produced a broadening anti-Negro sentiment in the North as well.

For a time many Northerners of antislavery descent placed their hopes in Booker T. Washington’s formula for racial progress. But in the 1890s and early 1900s some of these people began to feel a growing sense of desperation, anger, and militancy. The faith in gradualism, the trust in the good will of Southern whites, and the hope that evolution and education would solve the race problem broke down. The “new slavery” in the South, as some former abolitionists termed it, produced a new abolitionism in the North. This new abolitionism was not so strident, radical, or well publicized as the old, but it nevertheless represented a conscious revival of the antislavery impulse. The founding of the NAACP in 1909-1910 was, in part, the fruition of this movement.

The Boston Transcript, edited by Edward Clement, had been in the 1880s one of the foremost advocates of gradualism and god will toward the South. But events in the next decade caused Clement to despair of this approach. As early as 1889 the Transcript declared that “race rancor” was “increasing in inverse ratio to the distance from slavery, instead of dying out. At this rate a worse civil war than that of 1861-65 will come in a few generations.” Clement became an outspoken critic of lynching and disfranchisement. He termed South Carolina’s disfranchisement of Negroes in 1895 “The New Nullification,” and declared that the Supreme Court’s decision in Williams c. Mississippi (1898) upholding the disfranchisement clauses of Mississippi’s 1890 constitution “wiped out as with a sponge” the “entire work of the Republican party, so far as the political rights of the southern negro are concerned.” In 1899 the Transcript lamented that “the old slavery prejudice” was “almost as strong today as it was 40 years ago.” There was a “new crusade against the negro” to “deprive the black race of citizenship” which must be met by a revived crusade to protect that citizenship.

Wendell Phillips Garrison was also shaken out of his earlier complacency by events in the 1890s. In 1895 he wrote that lynching and disfranchisement were signs of the “unchanged spirit of slavery.” In 1903 Garrison told one of his brothers that “the great debate of the last century will be renewed in our latter years as it seemed settled in Father’s.” The “wave of reaction on the negro question,” said Wendell, must “raise a counter wave of conscience” as it had done in the days of abolitionism.

Other members of the Garrison clan expressed similar sentiments. William Lloyd Garrison, Jr., a successful wool merchant, became in the 1890s a prominent advocate of many reform causes, including woman suffrage, anti-imperialism, the single tax, and racial justice. In many ways he seemed to be a reincarnation of his father. He told an audience of Negroes in 1901 that if it were possible “to resurrect the old anti-slavery guard today” they would view the racial situation with “sadness and astonishment.” In the South “they would behold a race contempt unabated by emancipation, and lynching cruelties that exceed in savagery the deeds of Simon Legree.” In the North, “instead of indignation and protest, they would see the old pro-slavery prejudice against color revived.”

In 1906 Garrison proclaimed that “it is time for the colored people to organize for lawful self-defense and for white lovers of liberty to stand up for equal rights.” The increasing oppression of the Negro “is the very recrudescence of slavery. It must be met with the undaunted purpose that the abolitionists displayed, for the conflict is the same irrepressible one. This Union can no more exist on the basis of the enfranchised whites and disfranchised blacks than could a Union half slave and half free.”

In the early 1900s the owner of the Nation, Oswald Garrison Villard — grandson of the first William Lloyd Garrison — and his Garrison uncles were friends and supporters of Booker T. Washington. But after 1905 they became increasingly impatient with Washington’s attitude. Villard wrote in 1909: “I grow very weary of hearing it said that Hampton and Tuskegee provide the absolute solution to this problem.” With Washington “it is always the same thing, platitudes, stories, high praise for the Southern white man who is helping the negro up, insistence that the way to favor lies through owning lands and farms, etc., etc.”

In 1905 a group of Negro militants under the leadership of W. E. B. Du Bois founded the Niagara Movement as a protest organization to agitate for Negro rights. Villard was in touch with Du Bois and his followers, and in 1906 Villard began to discuss with Mary White Ovington, a white social worker who was the daughter and granddaughter of abolitionists, the idea of organizing a national society of whites and Negroes to work for equal rights by challenging discriminatory legislation in the courts, forming political pressure groups, and holding protest meetings to arouse public opinion. Miss Ovington supported the project: she wrote to Villard that “you and I were brought up on stories of heroism for a cause, and dreamed dreams of doing something ourselves some time.”

In the summer of 1908 a race riot at Springfield, Illinois, startled the country. Writing about the riot in the Independent, the Kentucky-born socialist William English Walling concluded that “either the spirit of the abolitionists, of Lincoln and of Love-joy must be revived and we must come to treat the negro on a plane of absolute political and social equality, or Vardaman and Tillman will soon have transferred the race war to the North.”

After reading this article, Miss Ovington arranged a meeting with Walling and Dr. Henry Moskowitz, and the three of them enlisted Villard to draft a call for a national conference to discuss the race problem. Villard’s call, issued on the centenary of Lincoln’s birth, proclaimed that “‘A house divided against itself cannot stand’; this government cannot exist half-slave and half-free any better today than it could in 1861…[There must be] a renewal of the struggle for civil and political liberty. Among the fifty-two white signers of this call were at least fifteen former abolitionists or their children, including William Lloyd Garrison, Jr., Fanny Garrison Villard, Edward Clement, William Hayes Ward (editor of the Independent), Horace White, and others whose memories and careers went back to the Civil War generation.

The first meeting of the National Negro Conference was held in 1909, and out of the second meeting in 1910 grew the formal organization of the NAACP, which absorbed the Niagara Movement. The NAACP was literally as well as symbolically a revival of the abolitionists crusade. The two leading spirits of the NAACP in its early years were Villard and Miss Ovington.

The NAACP revived some of the immediatism and fervor of the abolitionist movement. The race problem, said Villard in a 1911 speech on behalf of the Association, “will not work itself out by the mere lapse of time or by the operation of education…There is only one remedy — that the colored people shall have every one of the privileges and rights of American citizens.” Francis Jackson Garrison said of an enthusiastic NAACP conference in Boston that “it seemed like an old-fashioned anti-slavery meeting.”

During the NAACP’s campaign in 1913 to arouse public opinion against the segregation of Negro civil servants in the Post Office and Treasury departments, Villard responded to criticism that he was an extremist with the words: “No one who has ever made an impress in a reform movement has ever done so without being called a fanatic, a lunatic, a firebrand, etc. If in this cause of human rights I do not win at least a portion of the epithets hurled at my grandfather in his battle, I shall not feel that I am doing effective work.”

Thus a study of the antislavery legacy from Reconstruction to the NAACP reveals a greater complexity of attitudes and activities among former abolitionists than might appear at first glance.

Many persisted in the old faith until they died. Others modified their attitudes, and the nature of their modifications can tell us something about the Northern retreat from Reconstruction, the disenchantment with immediatism, the impact of Darwinism, the confidence in education, and the revival of militancy after 1890 in the face of the Negro’s deteriorating status. Many of the Northern liberals who became disillusioned with Reconstruction in the 1870s did not abandon their concern for Negro rights, but were genuinely convinced that reconciliation between North and South and the cooperation of the “best people” of both sections in behalf of education and economic progress offered the best hope for ultimate racial equality.

Of course, some men and women of antislavery background grew indifference to the Negro’s plight, turned to other concerns, or disappeared from public view. But in the first decade of the twentieth century several white people of antislavery descent came together with a number of other liberal whites and Negroes to found the NAACP. The NAACP was, in some respects, a self-conscious revival of the antislavery impulse. Thus one can discern a thread of continuity between the old abolitionism of the antebellum era and the new abolitionism of 1910; the thread is frayed and almost broken in places, but a close examination of its strands can tell us much about the course of race relations between the end of Reconstruction and the beginning of the NAACP.

* The Artist – Thomas Nast (1840-1902) was the foremost political cartoonist of his day. Period and artist were well-matched: It was the heyday of journalistic drawings — before photographs could be reproduced as they are now — and of great causes. Nast almost made the Civil War his own, reporting on it from its earliest days, making himself the eyes of thousands of readers.

He joined Harper’s Weekly in 1862 and it was his drawings as much as the editorials that made that magazine the most important organ of opinion in the North.

His pictorial commentary on the day’s issues had an influence and impact hard to imagine today. He originated some of our most popular symbols: the jolly round Santa Claus, Republican elephant, Democratic donkey, Tammany tiger.

This was originally published in the December 10, 1968 issue of PAW.

No responses yet