Martyrs of the Pump

A Dramatic Tale of the Civil War in Which a Secessionist Is Given the Water Cure, His Punishers in Turn Disciplined byt he Faculty, and the Whole Affair Concluded with a P-Rade.

A pump stood in back of Nassau Hall during the nineteenth century and provided water for the entire College of New Jersey throughout many creaking decades. But on one occasion it played a more sensational role in the drama of Princeton history.

On a dark September night in 1861, five months after the start of the Civil War, a group of Princeton students shanghaied a Confederate sympathizer from his dormitory room and placed him under the college pump where “that venerable institution was put into operation and continued to pour forth its aqueous contents until the fire of disunion was pretty well quenched in his breast.” The incident gained considerable local publicity, but might not have attracted outside attention were it not for an important aftermath which was widely publicized throughout the northern states.

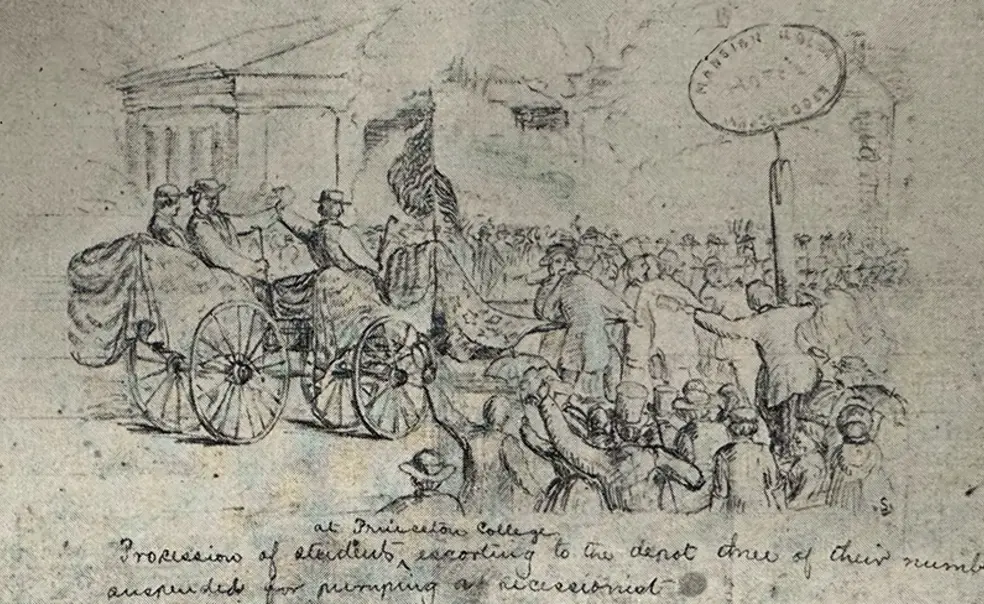

The story is fairly well known, but no illustration of it was believed to exist. The recently discovered drawing below shows the final act in the incident which contemporary writers referred to as “Pumping Out the Secessionists.”

President Maclean and the faculty were strongly Unionist in sentiment and publicly said so. Perhaps they secretly approved the water cure for young rebels in their midst. But they feared that anarchy would result if the student body were allowed to take the law into its own hands. Accordingly, the three men known to have assisted in the pumping were suspended from college.

The student body at this time was made up almost entirely of northerners, the southerners having left to join the Confederate forces the previous spring. Indignation swept the campus and a resolution condemning the action of the faculty was passed at a student mass meeting.

When the time came for the suspended students to leave town, a barouche was borrowed from a Mr. Fielder (described as “a gentleman and scholar in town”) and the three “martyrs” were carried to the train in royal state. The barouche was draped with five American flags and the heroes were pulled through the streets of Princeton and down to the railroad station the other side of the canal to the wildly patriotic cheers of the town’s inhabitants. An undergraduate P-rade, with fife and drum, preceded the carriage. Once arrived at the station, the “martyrs” were called on for speeches. They responded nobly, saying, in brief, that they’d do the same thing again. Representatives of the remaining student body then replied, lauding the conduct of the departing stalwarts, waving flag violently, and damning the faculty. “Flags floated in all directions,” said the Philadelphia Sunday Dispatch, “and the ladies in large numbers greeted the brave trio.”

The Culprits

The suspended students were Howard James Reeder ’63, Samuel B. Huey ’63 and Isaac K. Casey ’64. The fact that the faculty may have missed one culprit is suggested in the Class of 1863 Fortieth Year-Book where the Class historian erroneously states that along with the others Francis Reeder ’63 was suspended for “patriotic overwork at the pump handle.” The three men actually suspended several with the Union forces, two of them (Reeder and Huey) returning later to receive A.B. degrees. Casey died in 1867, but both the others had long and distinguished careers after leaving Princeton, Reeder becoming judge of the superior court of Pennsylvania, and Huey one of Philadelphia’s leading citizens and president of its board of education. Three of Mr. Huey’s sons are members of the present alumni body: Arthur B. Huey ’92, Malcolm S. Huey ’01, and Samuel C. Huey ’99.

The pumpers are described, but who was the pumped? In contemporary newspaper correspondence he was referred to as “F------- B-------, the Frenchman.” He was Francis DuBois, Jr., ’63, a young man who was careless in expressing his political views — but not “a conceited foreigner” as alleged. He was of Swiss parentage but born in Brooklyn. Undeterred by his experience at the pump, he stayed in college two years more, graduated with the class, and, remarkably, seems to have harbored no particular ill will against Princeton. There are even indications in ’63 Class Year-Books that he wrote to his class secretary at least occasionally — and for many years that functionary was Samuel B. Huey, one of the triumvir of pumpers!

Incidentally, the excuse given for the entire incident was the DuBois was a northerner. An anonymous correspondent of the Newark Daily Advertiser wrote: “The mere holding of secession sentiments by those born and reared at the South may admit, on some grounds, of palliation; but the open avowal of treason by one of Northern birth, the sarcastic sneer, the exultation at Federal disaster, the hopes expressed of our ultimate defeat and the disintegration of the happiest and most prosperous nation upon which the genial sunlight ever rose, is more than can be suffered by anyone who has a spark of fire in his eye.”

Respect for the southerners’ natural sectional loyalty is illustrated by another incident which happened soon after the firing on Fort Sumter in April 1861. A campus ceremony was planned, and according to the late Dr. John DeWitt ’61, as quoted in The Story of Princeton by Edwin M. Norris ’95, this is what happened:

To the committee having the ceremony in charge came a representative of the southern students in Princeton with the request that they might be permitted officially for the last time to salute the flag. And one — John Dawson ’61 of Canton, Miss. — asked that with his violin he might accompany the singing of the “Star Spangled Banner.” This was to be their farewell. The flag was raised. The salute was given. The southern students — not many, for must had hastened home — then marched off the campus, the northern students standing uncovered before them at salute. Before the next day most of them had gone.

The drawing which accompanies this article was discovered last spring by Nelson D. Burr, a Princeotn graduate student in history, who was working in the Watkinson Library, Hartford, Conn., on his monograph Education in New Jersey, which is to be one volume in a series on New Jersey history under the general supervision of Professor Thomas Jefferson Wertenbaker. The drawing is reproduced here by permission of the Watkinson Library.

Before concluding this account of the pumping incident, a grave wrong should be righted. One of the best stories of Dr. McCosh now seems to have been based on false premises. The story is that after a student disturbance of any kind Dr. McCosh would address the undergraduates as follows: “Young gentlemen, you will be bringing disrepute to me college. If you create a disturbance here, the first thing you know it will be in the New York papers. And the day after that in the Philadelphia papers.”

For the information of Robert McLean ’13 of the Bulletin, William C. Temple ’08 of the Inquirer, A.L. Thomas ’12 of the Public Ledger, and other loyal Philadelphians, it should be stated that the earliest New York mention of “Pumping Out the Secessionists” appeared on September 18, 1861, while the Philadelphia Daily News carried the complete details on September 17. Salute to the Quaker City!

This was originally published in the October 20, 1933 issue of PAW.

No responses yet