‘He did not want me growing up in a country run by gangsters’

Why a father in Nazi Germany sent his son to Princeton

In 1937, Max von Laue, a German physicist who had won the Nobel Prize in 1914, wrote his first letter to his son, Theodore von Laue ’39 *44, at Princeton. It was a time of rising authoritarianism in Germany; in the academy alone, Hitler and his government had fired Jewish professors, purged libraries, forced universities to adhere to the “Führer principle” (the supremacy of Hitler’s will above all laws and institutions), and defunded research in fields deemed not sufficiently “Aryan,” like theoretical physics and the social sciences.

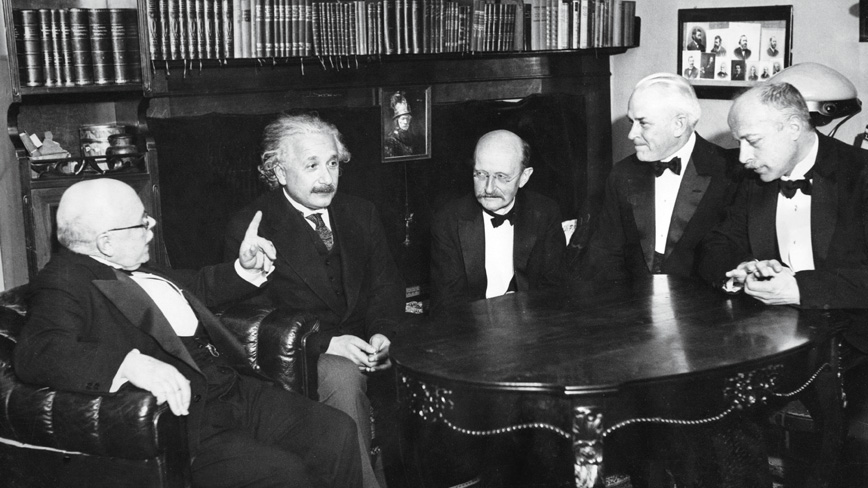

Von Laue, a friend of Albert Einstein, had visited Princeton the previous year to give a series of lectures. His biographer, Jost Lemmerich, suggests that Princeton offered him a professorship — he would have had to keep this quiet, because Germany might not have let him leave if they thought he was a flight risk — but he turned them down because he wanted to help his country resist its takeover by the Nazi Party. (“I hate them so much I must be close to them,” he told Einstein. “I have to go back.”) But he sent his son to attend college at Princeton, because, Theo later said, “He did not want me growing up in a country run by gangsters.”

Throughout Theo’s time at Princeton as an undergraduate and then a graduate student, he and his father exchanged letters — often weekly or more. Their correspondence is a remarkable record of two models of the university in collision: the collapse of German universities under authoritarian control and the American alternative. For von Laue, Princeton was the promised land, a place where he sent his son while he remained in hell, determined to make it better. PAW combed through archives at the Universitätsarchiv Frankfurt am Main and elsewhere to reunite their dialogue across an abyss.

Max von Laue was, in some ways, a quintessential German. A man with large melancholy eyes who wore soft professorial suits with the crispest of white collars, he had the broad humanistic education typical of the German gymnasium, which gave him, later on, a deep fund of history and letters to sustain him through turmoil, including an indelible love of the German writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. He studied physics at a time when many saw it as a dilettantish science because, he later wrote, its formal rigor appealed to his sense of beauty: “[A] beautiful, consistently mathematical proof was one of my greatest joys already at school,” he wrote in a memoir in 1961.

After Einstein fled Germany in 1933, von Laue found himself fighting an increasingly lonely battle against the madness that was taking over his country. As the director of the Institute for Theoretical Physics at the University of Berlin, where he also taught, he used his influence to do good wherever he could. He fought against the erasure of Jewish scholars from curricula. He protected Lise Meitner, a colleague of Jewish descent, from the purges targeting Jewish scientists. His colleagues later recalled (in Lemmerich’s biography) that he rarely walked outside “without carrying a parcel under each arm, since that gave him an excuse not to give the obligatory Hitler salute in greeting.”

Before putting his son on a ship to America, von Laue sat down and wrote him a letter, to be sent, apparently, to a friend at Princeton to pass along. “You should receive this letter immediately upon your arrival at Princeton, so that you don’t feel abandoned there,” he wrote. “Because that’s the feeling I have gotten from my own experiences when first arriving in a new place, where one only gradually finds their footing.” (The letters, written in German, are translated here.)

For his part, Theo reacted to Americans as any German would, alternately delighted with the friendly confidence he received as a stranger and “horrified” by the casual liberties of “these naughty, undisciplined children.”

“I have to say,” he said, “you can get along very well with these Americans. They are amazingly natural, childishly naïve, and unbiased.”

Theo decorated his dorm room (taking great pride in his “sophisticated chair”), made friends with local Quakers, and marveled at the chumminess of American teaching: “Instead of the students climbing up to the professors, the professors climb down.” He joined a student tutoring agency and tutored students in German. (He reported that an older Jewish woman on the ship to America had helped him with his conversational English.)

In Germany, meanwhile, the situation at universities grew steadily worse. The Nazis installed their own appointees in university administrations. They expanded their purge of the professoriate to include political dissidents. Having made it legally and socially acceptable to torment a class of people — Jews — they kept everyone else in terror by threatening to include them in that class. Von Laue’s opponents called him, and others who criticized the regime, “white Jews.”

Knowing his letters might be read by censors, von Laue often used abbreviations when mentioning colleagues at Princeton who had fled Nazi Germany — for instance, “P.” for Erwin Panofsky, “J. Fr.” for James Franck, and “We.” for Hermann Weyl. The most important events necessitated the vaguest phrasing. In July 1938, he wrote, “In Berlin, a rather painful change has occurred. Someone is leaving the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Chemistry, and I don’t even know where that person currently is.” He was referring to Meitner, whom he had warned of impending danger, and who managed to escape Germany in a terrifying secret train ride.

Literature became part of the code. Von Laue couched some of what he couldn’t say in obscure allusions for Theo to look up in Princeton’s library. In 1940, he asked casually, “Do you remember the little poem by Fr[iedrich] Rückert about Pharaoh, which I once recited at home and which you found very outdated at the time? It might seem quite modern now. You surely have Rückert’s works in your university library.” Had the censors looked up the poem he was referring to, Lemmerich notes, von Laue could have paid dearly for it:

To the evil spirit Pharaoh spake:

Help me and do thy part,

That in the eyes of my people

I seem godlike.

The demon said: Not yet

Has the time come for that;

First thou must needs do much evil,

Before it come to that.

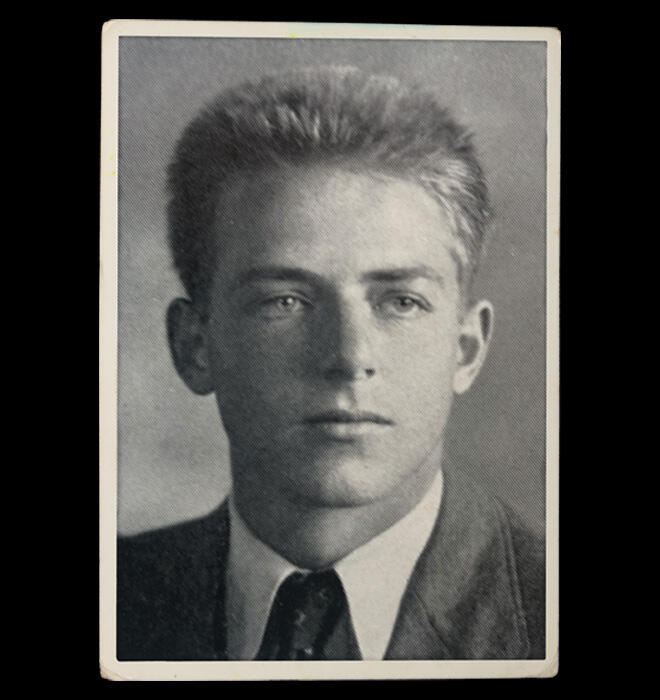

Theo graduated as a history major — his senior thesis was on 19th-century Germany — then started a history Ph.D. at Princeton. He didn’t want to be forced to join the German military.

Then, in December 1941, after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the United States declared war on Germany. Now the father and son were stranded in enemy nations.

They found ways to continue their correspondence. Whenever possible, they sent letters or messages to Meitner, now in Sweden, who forwarded them on.

Theo was now an enemy alien: an international student from a nation the U.S. government was fighting against. His sympathy was with the Allies, but that didn’t save him from political reprisal. In July 1942, the FBI arrested him and put him in detention — not for committing a crime, but for having once been compelled, like all German students, to join Nazi youth groups. Einstein, the history department, and other Princeton representatives intervened on his behalf and got him released.

As his fellow graduate students left, one by one, to join the war, Theo ran a newsletter to keep them updated on the campus and its former denizens. “Once more the History Club intends to meet regularly, in spirit at least, however scattered through the world its members may be,” he wrote in the inaugural issue.

As a freshman, he’d seen American higher education as something to be endured: “I wish you had to live in a dormitory for a day to cool down your American enthusiasm,” he wrote to his father early on. Now, on his way to becoming a professor himself, he made his newsletter a tribute to the American university — as a symbol of the free society they were fighting for. (It was also a venue for occasionally heckling Harvard, but even at its most heroic, Princeton has never been above that.)

In 1943, after von Laue persisted in criticizing the Reich while lecturing abroad in Stockholm, the ministry of education pressured him to stop teaching at the University of Berlin. He reluctantly assented. (In a speech at his funeral decades later, Meitner said she’d cautioned him back then that his actions during his visit might put him at risk. He said, “All the more reason to do it.”)

Ultimately, von Laue spent the war doing nonmilitary research and undermining the regime as best he could. On April 17, 1945, as Russian troops advanced toward Berlin, he wrote a fearful, moving goodbye letter to Theo. In it, he quoted Goethe twice, wrote of his wife’s strength and suffering, described the locations of friends and family members as well as his scientific papers, and told Theo that he loved him.

“If I survive this catastrophe, then my main task for the rest of my life will probably consist of contributing to the intellectual rebuilding of Germany,” he wrote. “I know how great a mountain of hatred will have to be overcome.”

As it turned out, he was captured by the Americans, in a mission, Operation Alsos, that aimed to secure the German atomic scientists before the Russians could get to them. They included von Laue, who wasn’t an atomic scientist, because they wanted him to help lead German science after the war. (He kept writing to his son during his captivity, though he didn’t know when he would be allowed to send the letters. “I may not say where I am writing from,” he wrote. “I have ‘disappeared,’ as Dr. Martin Luther once did at the Wartburg.”)

He wound up with the German atomic scientists at Farm Hall, a manor house in England that was set up as a genteel prison. It was thoroughly bugged, which allowed their minders to note the scientists’ shock on Aug. 6, 1945, when they learned the Allies had dropped an atomic bomb; they’d thought they were years ahead in atomic science, whereas Nazi science was so bad that they were years behind.

The minders also noted that von Laue was the only prisoner who wasn’t desperately trying to rewrite his personal history: “He is rather enjoying the discomfort of the others as he feels he is in no way involved.”

Upon his release, he asked immediately, “Do you think it is possible for me and my wife to go to our son at Princeton?”

After the war, von Laue did indeed become a scientific leader in helping Germany move past the destruction of Nazism. Much of the damage wasn’t repairable; German universities, which had previously been revered as the best in the world, fell far behind the United States, which benefited from the talents of scientific refugees and gained a reputation for tolerant generosity that attracted the best scholars.

For his part, Theo became a professor in the American model, wearing Ivy-style suits and bow ties. In an essay on teaching, he said he preferred to climb down and meet students where they were — to “win them by kindness.” He became a historian, he said, because history is a civic trust, a way to ensure horrors like the Holocaust aren’t repeated: “Salvation, then, lies in remembering properly, so that the living can survive and prosper.” He taught at Swarthmore College and elsewhere, specializing in the conditions that give rise to authoritarianism.

Today, their story serves as a reminder of not just the sacrifices that parents and children make to do right by each other, but also the power a university can have as a stronghold of ideals. Princeton meant something to von Laue, who referred constantly to the University even in letters to others, since so many refugees and dissidents wound up there, and von Laue, in turn, meant something to his countrymen.

“To all of us minor figures,” Paul Ewald, a physicist who left Germany in protest against the Nazi regime, later wrote, “the very existence of a man of [von] Laue’s stature and bearing was an enormous comfort.”

Elyse Graham ’07 is a professor at Stony Brook University and author of Book and Dagger: How Scholars and Librarians Became the Unlikely Spies of World War II.

4 Responses

Rocky Semmes ’79

2 Months AgoA Passing Mention Worth Pursuing

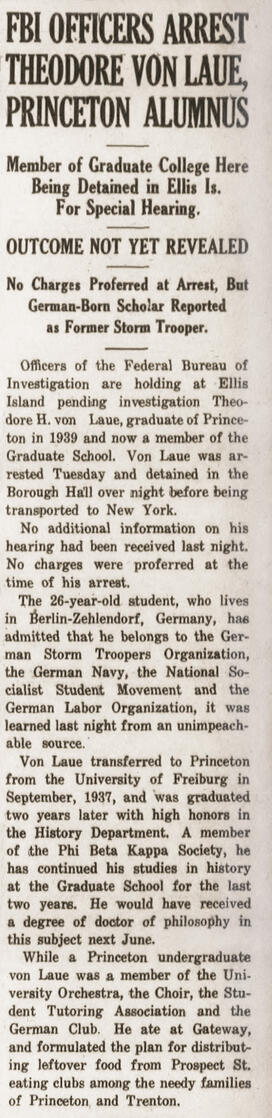

The recent article about critic of the Nazi Reich Theodore H. von Laue ’39 *44 included a period newspaper illustration. That excerpt included a text reference to von Laue having “formulated a plan for distributing leftover food from Prospect St. eating clubs among the needy families of Princeton and Trenton.”

That mention alone cements the man’s legacy as a significant and notable alumnus. Inquiring minds seek elaboration of that plan’s development and resolution. What happened to it? Will the staff at PAW consider a follow-up story?

Bill Carpenter ’73

5 Months AgoRelevant Lessons in a Cover-Worthy Story

Thank you so much for the great article, “Why a Father in Nazi Germany Sent His Son to Princeton.” It was a gripping account of how a Princeton family was affected by Hitler’s takeover of Germany.

Although I also enjoyed the cover article, “The Fall Guy,” the lessons from the Nazi Germany article are so relevant to Trump's attack on freedom of speech and thought, it seems that should have been the cover story, not The Fall Guy!

Hope you’ll find and print more stories on how we can fight back against the attack on our democracy and protect Princeton's independence.

George Griggs ’59

5 Months AgoModern Parallels to the von Laue Story

In the first paragraph of the Elyse Graham ’07 article, “The von Laue Letters,” if one were to advance the date by 90 years and substitute names and places, we would have an apt description of what’s happening in current day America. As Theo von Laue is quoted as saying, referring to his father, Max von Laue, “He did not want me growing up in a country run by gangsters.” Those of us who are fathers who love our children want the same. Can Princeton and like institutions continue as strongholds of ideals, as described by Ms. Graham, or will the damage being inflicted become unrepairable?

David Derbes ’74

5 Months AgoEinstein’s Greetings

I had not known that Theodore von Laue had been at Princeton. There is an anecdote in the wonderful and rather unknown chronicle of Einstein’s science by his former assistant, Cornelius Lanczos, The Einstein Decade 1905-1915 (p. 23). I quote it all:

“It was a rare privilege to be on ‘Du’ terms with Einstein, but one of these privileged persons was Max von Laue, the eminent German physicist. Von Laue received a Nobel prize for his ingenious idea of employing a natural crystal for the analysis of X-rays, thus demonstrating both their wave nature and the correctness of the molecular picture of a crystal as a regular lattice arrangements of atoms or molecules.” [Just this method was employed by Watson and Crick to determine the structure of DNA.]

“Laue was a man of absolute integrity, who behaved most wonderfully when so many colleagues failed during the emergency created by the Nazi era. He refused to accept a position abroad, because his own life was not endangered and he did not want to take away the opportunity for somebody who might need it more than himself. Thus, he preferred to stay in Germany and do the utmost possible (often with disappointing results) for those colleagues who came into difficulties. Einstein was tremendously impressed with the unbending honesty of his friend. Years after the Second World War an eminent physicist from Germany visited him in Princeton. As he was about to leave, he asked Einstein, whether he wanted to send greetings to his old friends in Germany. ‘Grüssen sie Laue,’ was Einstein’s answer: Greetings to Laue. ‘Yes,’ said the visitor, ‘I shall be happy to convey these greetings. But you know very well, Professor Einstein, that you have many other friends in Germany. Einstein pondered for a moment, then he repeated: ‘Grüssen sie Laue.’”