ROBERT M. MAY, Lord May of Oxford and a former professor and administrator at Princeton, died April 28 in Oxford, England. He was 84. May, who trained as a physicist but transitioned to pioneering work in theoretical ecology, joined the faculty in 1972 and chaired the University Research Board. Edward Tenner ’65, in a memorial for Scientific American, described May as brash and competitive but beloved for his candor and unpretentiousness. After departing for the University of Oxford in 1988, May served as the chief scientific adviser to the U.K. government and president of the Royal Society. He received an honorary doctorate from Princeton in 1996 and was awarded the Copley Medal, the Royal Society’s highest honor, in 2007.

Amy Baxter-Bellamy/ University of Pennsylvania

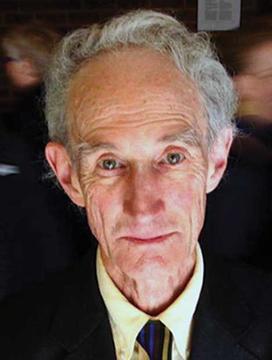

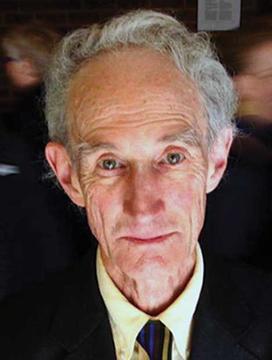

THOMAS ROCHE JR., the Murray Professor of English, emeritus, died May 3 in Beachwood, Ohio, at age 89. Roche, who joined the faculty in 1961, specialized in epic and Renaissance poetry and was a leading scholar of 16th-century poet Edmund Spenser. He mentored colleagues in his more than four decades on the English faculty and shared his love of Shakespeare with students by participating in productions of the Princeton Shakespeare Company.

HANNA HAND, whose work as a staff member and volunteer at the Davis International Center spanned more than 45 years, died April 27 from complications related to COVID-19. She was 85. Hand helped to pair international students and scholars with host families and assisted spouses and partners in adjusting to life at Princeton

4 Responses

George Gurley ’63

5 Years AgoA Contagious Love of Literature

Professor Thomas P. Roche (In Memoriam, June/July issue) was one of the best teachers I’ve ever had. His love of John Donne, Shakespeare, W.B. Yeats, and other great writers was contagious. I still carry around scraps of the immortal poems he introduced his students to. When I was a student a Princeton in the early ’60s, the English department was an exciting environment. Passionate scholars were devoted to close reading, the discovery of deep meanings, and the celebration of great literature, free of the political furies that seem to poison academia today. Erwin Panofsky at the Institute for Advanced Study and D.W. Robertston, the great lecturer on Chaucer, were major influences. I spent some bacchanalian evenings with Professor Roche and others students, along with Professor Hans Aarsleff, Sherman Hawkins, and the famous critic and poet R.P, Blackmur. Professor Roche was a fun and engaging teacher, but he didn’t have much patience for fools. I still have his comments on an irreverent essay I wrote about Milton’s “Lycidas.” — “This is the most disgusting effusion I have ever read — a hatchet job of unparalleled ignorance, a monument to the failure of the imagination...” I’m saving those words for my epitaph.

Richard M. Waugaman ’70

5 Years AgoShakespeare’s Sonnets

Thank you, Matthew Ferraro, for your tribute to Professor Roche. I was not fortunate enough to have him as a teacher. I do wonder, though, if taking a course from him would have left me with the freedom I’ve had to pursue the exciting Shakespeare authorship question for nearly 20 years.

When it comes to the "tired trope of biographical analysis" of the Sonnets, for example, I submit that trying to connect the Sonnets with the Merchant of Stratford is indeed pointless. Instead, the Sonnets reflect the autobiography of their actual author. I explored this in a 2010 psychoanalytic article about the bisexuality of the Sonnets.

My 90 publications on Shakespeare are here — http://explore.georgetown.edu/people/waugamar/.

William Brauer ’66

5 Years AgoA Life-Altering Class

The obituary for Thomas Roche Jr. in the June/July 2020 issue of PAW reminded me how T.P. Roche, as he was then known, altered the course of my life. I arrived at Princeton in 1962, ready to major in economics and pursue a career in business or government. As a distribution requirement, I took Professor Roche’s seminar on selected works of Shakespeare. I fell head over heels, graduated magna cum laude in English, and found a love of literature that stays with me to this day.

Thanks for leading me to the Pierian Spring, Professor, and for teaching me to drink deeply from it.

Matthew Ferraro ’00

5 Years AgoRemembering a Scholar and a Friend

Professor Thomas P. Roche Jr., who recently passed away, was a legend to generations of students. He was especially important to those of us who took part in campus theater productions. Tom was not only an enthusiastic participant in and supporter of productions on campus (I acted with him in several productions and even wore a suit of his as a costume in one), but also a generous host, friend, and mentor. Tom was one of the principal financial backers of a play that I produced in New York City my senior year — an off-off Broadway production of Damian Long ’98’s thesis project. He gave us the seed money we needed to rent the theater, and didn’t complain at all when we lost most of it.

The memorials of Professor Roche that I have seen so far have emphasized his kindness, personal generosity, and charismatic spirit. I feel that it is equally important, however, to note his exceptional scholarship. Tom was a scholar who surpassed Harold Bloom in his analysis of Shakespeare, Petrarch, and English Renaissance Literature. He used a rigorous understanding of religion and classical literature to completely upend about 150 years of Shakespeare scholarship. In his brilliant and frankly revolutionary analysis, he applied numerology and theology to Shakespeare’s sonnet sequence, putting the tired trope of biographical analysis (Shakespeare must have personally loved a Dark Lady and a Young Man!) to rest, and uncovering the allegorical nature of the entire sequence, in which the poet’s “wit” (the young man, and his poetic nature) competes with the poet’s “will,” (his work as a playwright and actor), all against the backdrop of a precisely structured chronological sequence that aligns with the calendar. Sonnet 33, for example, the “resurrection sonnet,” not only invokes Christ’s age and the trinity, but also falls exactly on Easter when the sequence is superimposed on a calendar. Tom showed us that in all this, Shakespeare not only created the best example of a renaissance sonnet sequence (there were many), but turned the form inside out — analyzing and transforming it into a meditation on creation and immortality. I know this seems esoteric, but as an undergraduate, it was like being handed a cypher to the Enigma machine. It was this experience, more than any other, that made me appreciate that I was at Princeton, because I could not have studied with Tom anywhere else. His analysis was like having a veil lifted from your eyes — it was impossible to un-see the truths he revealed. This was particularly detrimental in his Hamlet seminar, which left one with a deep loathing of the title character and an inability to watch almost any production.

Tom Roche was a world-class teacher and a true friend — funny, brilliant, generous, and kind. He will not be forgotten by those who knew him.