Princeton’s football team is off to a hot start in 2021, and as the Ivy League season builds to its conclusion this November, the Tigers will meet both Harvard and Yale in crucial games on Powers Field at Princeton Stadium.

While the stadium may feel like an institution to modern Princetonians, this year marks only the 25th anniversary of the Tigers’ current home. Before 1996, Princeton played its games in the fabled Palmer Stadium. That October, Bill Robinson ’39, who covered the team as a sportswriter for 28 years, documented the celebrated history of the Tigers’ home turf, recalling his fondest memories of the longtime home of the Orange and Black as it entered its swan song.

Yachts, Tailbacks, and Titles: Memories of Palmer Stadium

By Bill Robinson ’39

(From the Oct. 9, 1996, issue of PAW)

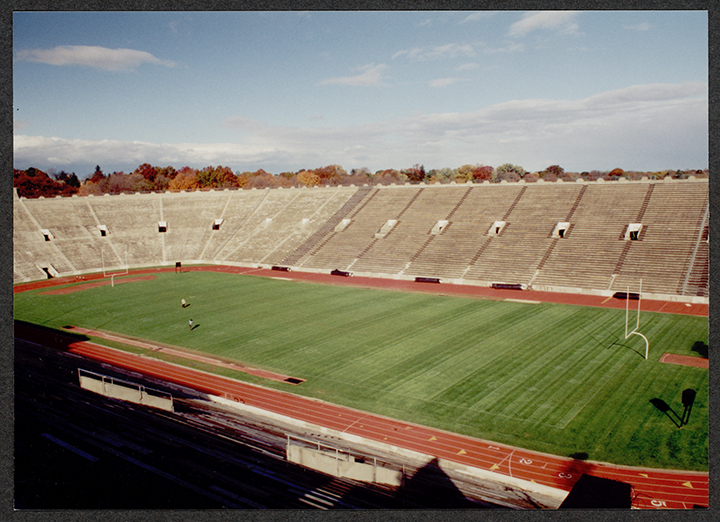

Palmer Stadium, one of the most storied monuments in collegiate football, a handsome edifice, and a wonderful, atmospheric setting for the sport, is sadly in its last season, and its impending demise invokes a host of memories. Built in 1914, the stadium was a gift from Edgar Palmer ’03, and it opened with a 16-12 victory over Dartmouth on Oct. 24 in that year. Since then there have been several periods of undefeated glory, a few not-so-glorious times, memorable heroes, and some storybook games. Having hosted 82 years of solid football, Palmer has played a significant part in the growth of the game.

The stadium’s history could, and probably should, make a book. This, however, is a short trip down a long and personal memory lane that started in 1930. I have taken in all but a few home games since 1935, including 28 years in the press box as a sportswriter for the Newark News and the Newark Star-Ledger, and one highly personal period as the father of a Tiger player, tight end Robby Robinson ’65. (When he walked on the field for his first game — as a sophomore in 1962 — I, who am not a smoker, ate a whole pack of Life Savers in five minutes.)

I have to confess that on my first visit to Palmer, for the 1930 Lehigh game, I was cheering for Lehigh (which won 13-9). A 12-year-old with no thoughts yet about college, I was with my uncle, a Lehigh alumnus. It was the week before the classic “Roper’s last game” (which I heard on the radio), in which coach Bill Roper’s final team, a heavy underdog to Yale after a dismal season, fell short of a monumental upset by one yard at the end of a heroic march as a rainy dusk settled over the field.

I soon became a Tiger fan, and memories of other early visits include the sight of a phalanx of tan, camel’s-hair polo coats, the de rigeur uniform of the Tiger cheering section (which was then on the sunny side of the stadium, where it remained until World War II). Approaching the stadium from Lake Carnegie, a fan could see large yachts along the bank of the Delaware and Raritan Canal, with white-coated stewards serving guests in nautical “tailgate parties” on the yachts’ fantails.

One of the great games of that era, which I happened to see and which more than ever confirmed my ambition to come to Princeton, was 1932’s 20-0 victory over Columbia (which went on to win the Rose Bowl) by coach Fritz Crisler’s undefeated team. Its most memorable moment was a 55-yard punt return by swift seat-back Gary LeVan ’36, at the end of which he juked past Columbia’s all-everything hero, Cliff Montgomery, to score, leaving Montgomery flat on his face on the track after a missed tackle.

My freshman year started with a big thrill, a 7-6 squeaker over Penn before a wildly cheering crowd of 52,000 in a renewal of a series that had been interrupted since 1896. Another memory of that year was the day of the Rutgers game, when my second freshman football teammates and I returned to the gym after playing Lawrenceville to hear that the varsity was trailing 6-2 at the start of the fourth quarter. We made a mad dash toward the stadium in horrified disbelief, only to be told by people leaving the game that Princeton had scored, and scored again. By the time we arrived, out of breath, the Tigers had won, 29-6.

The most memorable game of that 1935 season was the Dartmouth game in the home finale. There had been a tremendous build-up, as both teams were undefeated, and the all-time record crowd of 56,000 was packed into every corner and boosted by the temporary stands in the end zone. The game was played in a blinding snowstorm, the weirdest atmosphere I ever remember at a game. The snow prevented people in the upper rows from even seeing the field. As if these circumstances were not enough, this contest became notorious for the incident of the “12th man,” a drunk from the north endzone who staggered out through the snow and lined up in Dartmouth’s goal-line defense. His heroic effort, quickly snuffed by the startled officials, went for naught, as the Tigers scored to cap a 26-6 victory. No other game has ever quite matched that one.

After these glory days, things went downhill for a few years, although the 26-23 loss to the Elis (with their stars, tailback Clint Frank and end Larry Kelley) in 1936 was probably the single-most exciting game I ever saw at Palmer, or anywhere else, one of those up-and-down-the-field thrillers that the last team with the ball wins. Unfortunately, the Tigers were next-to-last.

After World War II, it took a while for the program to gather steam under the forceful leadership of coach Charlie Caldwell ’25, who made a work of art out of the supposed outmoded single wing. His first star was wingback George Sella ’50, whose heroic feats made every game exciting, and he kept building momentum through the 1949-51 glory years of tailback Dick Kazmaier ’52.

With Kaz’s remarkable knack for making a big play at the right moment — accompanied by perfectly drilled platoons and a defense led by tackle Hollie Donan ’51 — Princeton made every game a thrill to watch. The Tigers’ crowning achievement was a 53-15 swamping of an undefeated Cornell squad, in 1951. Kaz’s performance that day helped get him selected as Princeton’s only winner of the Heisman Trophy. Amid all Kaz’s heroics, one play in 1949 against Yale stands out as typical of his cool control. On a pass play in Yale territory, with the game in doubt, the center’s snap went over his head. As he spun around to go after it, the ball bounced right back to him. So he turned back around and tossed a perfect touchdown pass to Sella to clinch the game.

The next mantle of stardom fell on tailback Royce Flippin ’56, whose career was hampered by a leg injury in a preseason scrimmage with Syracuse. (While playing safety, he was blocked by Jim Brown — the Jim Brown — and his leg buckled.) He missed a lot of action, but always managed to make key plays, and winning touchdowns, against Yale.

By my main memory of Flip in action was only indirectly in Palmer Stadium. At a coaches’ convention in a New York hotel, a purveyor of movie cameras used by coaches for game films was demonstrating one of his wares by projecting a picture out of his room, onto a corridor wall. As Yale’s coach, Jordan Olivar, was hurrying down the hallway, the camera projected a picture — seemingly out of nowhere — of Flip running 70 yards for a game-winning touchdown against Yale. Olivar cringed in horror at the sight, shaking his fist at the image on the wall as he fled to the elevator.

The next memorable era belonged to fullback Cosmo Iacavazzi ’65, and included our last undefeated season, 1964. The lasting image I have of Cosmo is of him powering, airborne, into the end zone in a wedge play, scoring one of his record 31 career TD’s.

This was an indication of the tough football the Tigers put out for Dick Colman. Though a very different personality from the terse Caldwell, the smooth-talking Colman had the same devotion to the single wing and the same ability to inspire his team to top efforts. It is interesting that Caldwell and Colman had the same winning percentage, an outstanding .694.

Then came a mostly low period for Princeton, highlighted mainly by the Tigers’ upset of an undefeated Yale in 1981, in which the team, led by quarterback Bob Holly ’82, scored with four seconds to go win the game, 35-31, ending a 14-year losing streak against the Elis. That was my second-most-exciting game in Palmer.

When Steve Tosches took over, he set the Tigers back on a winning road, which reached a climax in the exciting feats of tailback Keith Elias ’94 and the 1995 Ivy title. It would be a wonderful end to all this history if Princeton could get a repeat title in the good old arena’s last years.

Go Tigers!

No responses yet