Meredith Martin ’97 Explores France’s Global Role in the 18th Century

Through multiple media, Martin is illuminating a little-known piece of history

Meredith Martin ’97 has seen three major projects come to fruition in the last year: an exhibition, a ballet, and a book. All involve different aspects of 18th-century French art and culture, the area in which Martin is a professor at NYU — and she collaborated with other experts on all of them.

“I don’t like being the academic toiling in isolation,” says Martin. “I think it’s more generative and inspiring to work with people in other disciplines.”

Martin teamed up with Nina Dubin and Madeleine Viljoen to curate “Fortune and Folly in 1720,” an exhibition that opened at the New York Public Library’s Stephen A. Schwarzman Building on Sept. 23. It explores the world’s first international financial crash, which wiped out investors in Paris, London, and Amsterdam. The physicist Isaac Newton lost a considerable amount of money in the collapse, which reportedly moved him to lament, “I can calculate the movement of stars, but not the madness of men.”

Fomented by the Scotsman John Law, “a Casanova who was really good at math,” as Martin writes in the book that accompanies the exhibition, the crash inspired printmakers to produce numerous satirical images for popular audiences. In one of the best known, a naked woman — Fortuna, or Fortune — dispenses to a crowd of people papers that recalled the stock certificates that plummeted in value along with the emotions that accompanied the boom and bust, including “extreme joy,” “sorrow,” “madness,” and “poverty.”

Martin and Dubin, a professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, first discussed in 2017 a project to mark the 300th anniversary of the Mississippi and South Sea Bubbles. Soon thereafter Martin had lunch with Viljoen, a curator of prints at the New York Public Library, which has a rich collection of material on the bubbles, in part because of the fascination they have long held for people in the financial world such as J.P. Morgan, who donated part of his collection of items on the 1720 crash. The exhibition was planned for 2020 but postponed because of the pandemic.

Last year, Martin joined with choreographer Phillip Chan on a production of the Ballet des Porcelaines that debuted at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in December and has since been performed in a number of venues. Written by the comte de Caylus, a French nobleman, in 1739, the work tells the story of a Chinese sorcerer who rules a mythical land called the blue island and turns the inhabitants into porcelain. A prince and princess arrive on the island, and the sorcerer turns the prince into a teapot, forcing the princess to bring her lover back to life. The couple then turns the sorcerer himself into a porcelain figure. Chan and Martin worked with a mostly Asian-American creative team on the project.

How about just a slight change at the end: “Porcelain was this very sexy, fascinating material in the 18th century,” Martin says. “It has a really interesting history and cross-cultural elements,” and performing the ballet seemed like the best way to convey that sense of excitement.

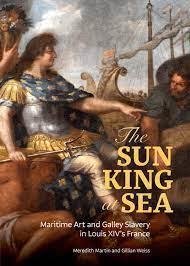

Martin was preparing to give a lecture on Versailles, she says, and came across an image of a painting where Louis XIV subjugates three enslaved figures. She hadn’t seen the painting but emailed it to Weiss, whom Martin knew well because Weiss grew up with Martin’s husband. The work intrigued Weiss, who had spent years doing research in archives in Marseille on 17th century French naval culture. The two found about 200 related images online and won a grant to do further research at maritime museums in France.

Despite the disparate media they involve, Martin says that all three projects explore France’s role in a wider world as scholarly interest has shifted to a more global view of its 18th century history. Her work, she says, “draws attention to objects, stories, and histories that haven’t been told.”

No responses yet