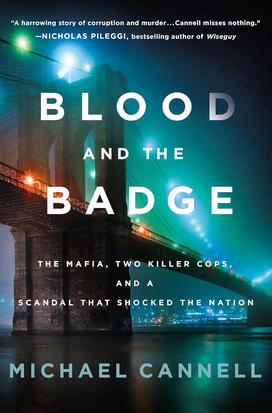

Michael Cannell ’82 Writes About Cop Corruption

The book: In Blood and the Badge (Macmillan) Michael Cannell ’82 details the crimes of Louis Eppolito and Stephen Caracappa, two New York cops who were double agents for the Mafia. The duo’s corruption spanned more than 10 years. They would alert those they were working with of everything — any evidence the police had against the organization, mobsters who were secretly cooperating, warning of phone taps, and more. Although evidence of their crimes came to light in 1994, Eppolito and Caracappa did not get charged until 2009. In this true crime account, Cannell details what happened and brings to light new research and interviews to explain such an egregious case of corruption.

The author: Michael Cannell ’82 earned his bachelor’s degree from Princeton in anthropology. He is the author of several books including A Brotherhood Betrayed. He was previously an editor at The New York Times and contributed to The New Yorker among other publications.

Excerpt:

A Homecoming

On an early October Day in 1979, A 31-year-old detective named Louie Eppolito and his wife, Fran, drove their blue Chrysler New Yorker from their home in the Long Island town of Holbrook to a Brooklyn funeral parlor to pay last respects to Louie’s uncle, Jimmy Eppolito, who was known to his associates in the Gambino crime family as Jimmy the Clam.

Until his shooting death on the night of October 1, Jimmy the Clam had served as a capo, a man of status and authority who for two decades commanded a crew plying the dark trades of loan sharking, bookmaking, and burglary.

Dignitaries from all five New York crime families, allies and adversaries alike, gathered at the wake to honor a well-liked Mafia veteran marked for death through no fault of his own. While the families variously collaborated and feuded, often with mortal consequences, they by custom convened at wakes and weddings for a few peaceable hours of small talk and ice-cold geniality. In the underworld, wakes were work events.

A parade of middle-aged men entered, wearing wide-lapel suits and broad ties. They had arranged their hair in Brylcreem pompadours, comb-overs, and shameless toupees. Let us assume the room smelled of Parliament cigarettes and Aqua Velva aftershave, the odor of underworld gatherings. Bodyguards, cronies, and hangers-on stood at a discreet remove while bosses shook hands, squeezed arms, crossed themselves, and bowed heads in doleful expressions of mourning. They spoke in low, gravel-throated tones in English and Italian. Jimmy the Clam was a good man, they said, a man of honor. Che tragedia. What a tragedy.

Louie Eppolito was hard to miss among his uncle’s mourners. He was a big man with a weight lifter’s physique gone to paunch. If he resembled anyone, it was Jackie Gleason. With a mustache and gut, he looked like a greaser dressed in a size-fifty suit for a casino night. One by one the mafiosi shook his hand. They kissed both cheeks in the Mafia manner, and asked after his daughters, Andrea and Deanna, and his son, Tony.

For Eppolito, the funeral was an uncomfortable homecoming of sorts. He was born into an established Mafia family, but he worked as a New York City detective. Police regulations prohibited him from fraternizing with criminals.

In a strict professional sense, Eppolito stood for these few hours behind enemy lines, though the surroundings were familiar. He had grown up among these men. A handful had visited his childhood home in East Flatbush, a Brooklyn neighborhood then known as Pigtown, where they conferred with Eppolito’s father, Ralph, known as Fat the Gangster, who had teamed up with Jimmy the Clam and a third brother, Freddy, in the Gambino operations. Their associates knocked on their door at odd hours. They huddled in the living room and spoke in low tones.

Louie, meet some friends of mine, Fat the Gangster would say. Louie stood and shook hands. They nodded in approval. Kid has a lot of respect, they said. His father often left with the men. The family might not see him for days.

Young Louie learned respect the hard way. His father was a short, stout man with an abusive temperament. In Louie’s recollection, his father hit for the mildest infraction. “I’d get smacked for looking the wrong way at my mother,” Eppolito later wrote in a memoir. “I’d get smacked for using the wrong tone of voice with my sister. I’d get smacked for being more than thirty seconds late for dinner.” Ralph hit his son with fists or whatever was handy—a two-by-four, a ketchup bottle, and, on one occasion, an Italian baguette. It was tough love, but without much love.

Ralph delivered his smacks with lectures on the Neapolitan code of conduct: always shake hands, show respect to family and strangers alike. No matter what, avoid dishonoring the family with una brutta figura, a bad showing.

When Louie turned twelve, he joined his father on afternoon trips to a private room above the Grand Mark Tavern, in Bensonhurst, where his Gambino associates talked business over rounds of craps and a Sicilian card game called Ziginette. Louie carried drinks and swept up. He also played errand boy. Every day he delivered an envelope of cash to patrolmen who, by long-standing arrangement, parked across the street, in front of Za-Za’s pool hall. Louie was careful not to hand the envelope directly to a cop, only to drop it onto an empty car seat.

Fat the Gangster hated the Irish-heavy police with an inordinate fury. “I guess my father despised them because they could be bought so cheap,” Eppolito said.

One afternoon in March 1968, Louis, by then nineteen, returned home from his job as a telephone installer to find his maternal grandfather standing outside their apartment building. “You better head inside fast, Louie,” the old man said. “Everybody’s crying, and I think your father’s dead.”

Fat the Gangster had died of a heart attack. Days later, a cortege of 18 black limousines carried gamblers and hit men, capos and consiglieri to a funeral mass at the Church of St. Blaise. FBI agents watched from a distance.

Within weeks of the funeral, Eppolito did what his father would have hated most: he enrolled in the police academy.

Eppolito passed his defection off as caprice. He applied without much thought, he said, after coaching his brother-in-law, Al Guarneri, as he jogged and jumped rope in preparation for the police academy fitness test. Eppolito lied about his family’s ties to organized crime in the NYPD screening, though it may not have mattered. The academy had relaxed its background checks to replenish its ranks after the Vietnam-era draft drastically reduced the applicant pool. With race riots and anti-war protests flaring, the NYPD would hire practically any young man capable of lacing up shoes and walking the streets.

Eppolito claimed to have signed on impulsively, though it is hard to see his enrollment as anything but an act of rebellion against his abusive father, a defiant slap back that he dared not deliver until his father had passed. His friends and family could scarcely believe his change of allegiance. “They all told me I’m crazy,” he said. “What do you want to do that for?”

Even in the academy Eppolito could not escape his father. During a lecture, a police instructor showed recruits a hierarchical chart of organized crime figures—soldiers, capos, consiglieri, and bosses—illustrated with mug shots and grainy surveillance photos. “Hey, Louie,” a classmate said, “there’s a guy with your last name.” The jowly man in the mug shot was his father.

Excerpted from The Blood and the Badge by Michael Cannell. Copyright © 2025 by Michael Cannell and published by Macmillan. Reprinted with permission of the author.

Reviews:

“Disturbing... jaw dropping... Cannell paces the proceedings like a thriller.” — Publishers Weekly

“Michael Cannell’s Blood and the Badge details the extraordinary investigation of the ‘Killer Cops’ investigation, a harrowing story of corruption and murder within law enforcement itself. Cannell misses nothing.” — Nicholas Pileggi, bestselling author of Wiseguy and co-writer of Goodfellas

No responses yet