Michael Park ’98 can walk down the street in his Manhattan neighborhood and go unrecognized — even as his judicial rulings from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit touch and shape the lives, in ways both large and small, of the nearly 25 million people who reside in his three-state territory.

During his years as a lawyer before becoming a judge, Park led litigation to advance a conservative legal agenda on some of the country’s most hotly contested culture war issues — from cutting off Medicaid funding to Planned Parenthood in Kansas to ending affirmative action at Harvard. He’s also a longtime member of the Federalist Society, a conservative legal network — all of which can leave people surprised to learn that Park has been happily married for nearly two decades (and counting) to a prominent liberal legal scholar and criminal justice reformer, Sarah Seo ’02 *16.

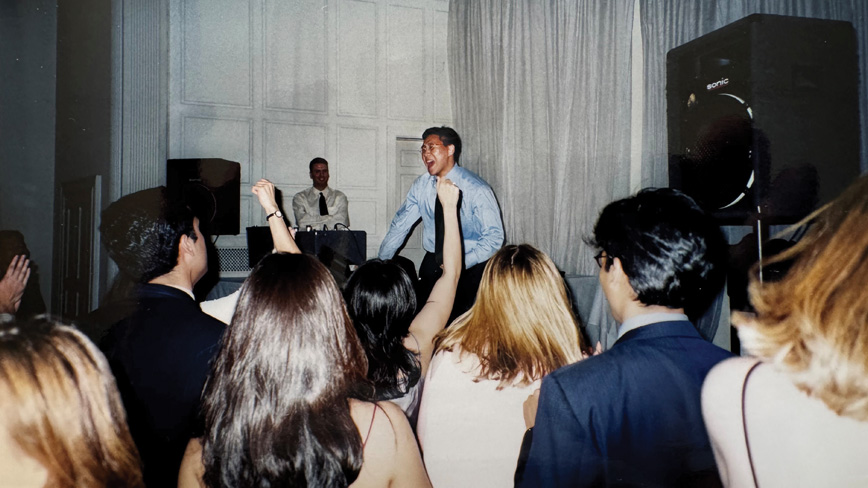

Park’s personality is low-key, and he is unabashedly geeky when it comes to the law. Yet the same man who describes the lifestyle of a judge as “monastic” can also light up a stage with his dance moves.

In today’s sharply divided political environment, where people like to paint public figures in black and white, Park is not so easily caricatured. But understanding who he is, how he thinks, and some of the seeming contradictions he embodies may soon be a matter of national interest. Because figures across the partisan spectrum agree that Judge Michael Park could well become Supreme Court Justice Michael Park.

“Were there a vacancy this administration, Judge Park’s age [49] puts him in the sweet spot,” says Mike Fragoso ’06, who worked on Park’s nomination to the Second Circuit in 2019 when Fragoso served as chief counsel for nominations for the Senate Judiciary Committee. “If the Republican lead in the Senate shrinks, in particular, he would be in a strong position as a nominee for whom one can count to 50 votes without compromising jurisprudence.”

An article in Bloomberg Law put it plainly, saying Park is “likely to be on [President Donald] Trump’s Supreme Court shortlist.”

Even Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito ’72 says Park, who clerked for him twice, has the right stuff. “Nomination to the Supreme Court is like being hit by lightning,” Alito tells PAW in an email. “That said, Mike would make a superb choice.”

Park’s ascent to the upper echelons of American law and government began halfway around the world, more than half a century ago, in the poor, rural community of Geumsan, South Korea, about 100 miles from Seoul. Park’s father, Ok-choon, grew up in Geumsan and lost his own father to a stomach ulcer when he was 10 years old. No one else in his family had ever gone to college, but Ok-choon knew education was his only way up.

In 1974, just 10 days after marrying his wife, Young-soon, Ok-choon flew to America to begin a Ph.D. in instructional psychology and technology at the University of Minnesota, with a focus on how people learn from computers. Young-soon joined Ok-choon one year later, and Park was born a year after that, in 1976, in the St. Paul suburb of Roseville, Minnesota.

Ok-choon and Young-soon befriended a lifelong Minnesotan whom they called Mr. Michaelson, who lived nearby with the children he’d adopted from Korea. When Park was born, his first name, Michael, was in honor of one of their first American friends and a nod toward their belief that they could forge a lasting sense of home in their new country.

When Park was 10 years old and his sister Christine ’04 was 4, the family moved to Springfield, Virginia, when his father took a job as a senior research psychologist at the U.S. Army Research Institute. Park excelled academically as a student at Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology, a nationally top-rated magnet school, and remembers “some tiger parenting stuff” from his parents. “The message was ‘Do your best, but if you get an A-minus, then you didn’t do your best,’” he says.

As freshmen at Princeton, Park and Arden Lee ’98 were assigned to singles in Butler residential college. One day, Lee walked into Park’s dorm room and spotted the self-help book The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People prominently perched on Park’s nightstand. Park’s instinct was “to always seek out the most rigorous thing,” Lee says, including being “that guy who freshman and sophomore year would take engineering classes knowing that he wasn’t going to become an engineer.”

The two friends got involved in Manna Christian Fellowship freshman year. The organization — which still has a robust presence on campus three decades later — had been founded one year prior. Members would gather for alcohol-free fellowship, singing, and a sermon on Saturday evenings in Murray-Dodge Hall, and by his junior year, Park was Manna’s president. As for the party scene on Prospect Street, Park says, “It wasn’t for me.”

He had come to Princeton with conservative leanings and values, which cemented across his four years on campus.

“I think it was a combination of my parents’ immigrant experience and seeing the importance of hard work, plus my faith background,” Park says. “The last piece came in college studying economics and policy [especially Milton Friedman], which pushed me in a conservative direction.”

Through his sophomore year, Park thought he would major in economics and pursue a Ph.D., but he increasingly felt economics was too theoretical and decided to major in what is now called the School of Public and International Affairs.

A formative moment came when Park was taking a seminar on health policy junior year with Dr. J. Michael McGinnis, an epidemiologist who had served as deputy assistant secretary across numerous presidential administrations for the Department of Health and Human Services. Park recalls McGinnis talking about how as a physician he had been able to help prevent infant mortality one patient at a time, but when McGinnis became a government official, he could implement policy changes that translated to thousands of lives saved. The impact was bigger, even if it felt less personal — a tradeoff that resonated with Park.

“I’ve always been a bit more of a head-over-heart person,” Park says.

Park went straight from Princeton to Yale Law School. There, his classmate Anjan Sahni, now managing partner of the law firm WilmerHale, remembers how students would sit in class and take notes at a feverish clip.

“I would then compare notes with Mike afterward and see that he would have taken notes by hand and after a two-hour class would have written down literally two sentences, boiling down the essence of what the class was about,” Sahni says. “At first, I laughed at that but then thought there was a method to what he was doing. He was paying extremely close attention. To this day, I remain impressed by his remarkable ability to very quickly cut to the chase of what really matters in a case.”

Though Park generally kept a low profile, he was in the spotlight at a banquet for law students in the lead-up to graduation. One of Park’s friends nudged the DJ to call Park on stage and perform the dance that accompanied ’N Sync’s “Bye Bye Bye.”

“The song comes on and he just nails all the Justin Timberlake moves,” Sahni remembers. “Everyone was speechless.”

While living in New York the prior summer, Park and his roommates had repeatedly watched a video of how to do the dance. But Park admits he might have been graded on a curve.

“Compared to the world at large, it was probably a B performance,” he says. “Relative to the dancing ability of my YLS classmates, it was an A-plus.”

Unsure of exactly what he wanted to do following law school, Park pursued a clerkship with a federal judge, sending out several dozen applications, hoping to find a position in the New York City area. Park landed a clerkship with Alito, who was on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit in Newark.

“He gave us a lot of independence in terms of working up cases and then wanted to talk through them with us,” Park recalls of Alito, who also graduated from Yale Law School. “There was a lot of back and forth. I remember being surprised that he cared what I thought.”

“I knew he was exceptional,” Alito says, “very smart, hardworking, dedicated, and a delight to work with.”

Following his clerkship, Park joined the New York office of WilmerHale as an associate, until he moved to Washington, D.C., in 2006 to spend two years working in the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel. In 2008, Park returned to Alito’s chambers, this time at the Supreme Court.

“I reached out to him and asked him to clerk again because I knew I would be getting a gem,” Alito says.

The line that famously and prophetically accompanied Alito’s picture in the Nassau Herald his senior year at Princeton read, “Sam intends to go to law school and eventually to warm a seat on the Supreme Court.”

Park, by contrast, had enjoyed his two clerkships, but upon completing the second one, had no intention of ending up on the bench.

In 2002, around the time he was completing his first Alito clerkship, Park attended a wedding in Princeton of two fellow Princetonians and was seen “going around the reception asking for a ride back to D.C.,” according to Seo.

Seo had matriculated at Princeton just after Park graduated, and the two had never formally met. She was, however, aware of Park because he’d returned to campus to give a talk to Manna students, and she was a member.

“Sure, I’ll give you a ride,” Seo told Park at the wedding reception.

During the nearly four-hour drive, they discovered how much they had in common: Seo had immigrated to the United States from South Korea with her family when she was 5 years old. Both were raised in Christian homes. Both were interested in law and policy.

Contrary to Park’s conservative worldview, Seo had completed a certificate in women’s studies and spent a lot of time thinking about, as she puts it, the intersection of her “faith and growing feminism.”

“Navigating those two ideas was a big part of my Princeton experience,” she says.

On the road they talked about both the moral and legal facets of abortion. Seo recalls that it was “not a debate” but rather “a very thoughtful conversation … . What I remember from that car ride is that Mike was not scared off when I said I was a feminist. He took me seriously and [engaged] respectfully.”

As they approached Park’s destination in Springfield, they realized their parents lived just 10 minutes apart.

The two hung out that summer until Seo left to teach in China as part of Princeton in Asia. The SARS outbreak forced her to return early, and a little over a year after that car ride, Seo started at Columbia Law School, by which time Park was working in Manhattan as an associate at WilmerHale. They began dating in 2003 and got married in 2008. Seo is now a professor at NYU School of Law.

While Seo remains steadfast in her liberal worldview, she acknowledges and appreciates how Park’s “traditional family values means that he is a hands-on dad, which makes it easier for me to pursue my career.”

She frequently gets asked about how a liberal woman working in academia and a conservative Trump-appointed judge can sustain a happy marriage.

“I always say that we never doubt the other person’s goodness, and the policy differences come from the same values,” she says.

In 2015, after a decade at top law firms, two years at the DOJ, and two clerkships, Park became a partner at the new boutique firm Consovoy McCarthy Park, which went on to be at the forefront of several high-profile cases, including litigation seeking to end affirmative action in college admissions.

As counsel for the organization Students for Fair Admissions, Park helped develop the case and craft the legal argument that race-conscious admissions policies at Harvard discriminated against Asian American applicants. In 2023, when Park was already on the bench, the Supreme Court ruled 6-3 in a landmark decision that the use of race as a criterion in college admissions violated the 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause.

Park was gaining notoriety in conservative legal circles when, in 2018, Jed Doty in the White House Counsel office called him out of the blue. “Part of me wondered if it was a prank,” Park remembers. The White House was gathering names for various judicial vacancies, including a U.S. Second Circuit Court of Appeals seat. When Doty asked Park if he’d be interested, Park said, “Sure!” but also understood the process to be at a very preliminary and uncertain stage.

At the time, the U.S. Senate tradition known as “the blue slip” remained in full effect, allowing home-state senators to decline to return their so-called blue slip in support of a nominee, effectively dooming the nominee’s chances of confirmation.

When Park met with Sen. Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., as part of the process, he remembers “going in thinking I could persuade him that I’m conservative, but fair,” Park says. Instead, the then-Senate minority leader “arrived late, left early, was grumpy the whole time, and spent most of it railing on the Federalist Society,” says Park.

After Schumer and Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand, D-N.Y., both declined to return their blue slip in support of Park, he moved on from thinking he was going to become a judge. Then he got another surprise call from the White House: President Trump and the Republican-led Senate Judiciary Committee were proceeding anyway with nominating Park.

Park says he likes that “I’m never recognized in public except maybe if I’m at a law school,” which made the day of his Senate confirmation hearing “daunting.”

Pushed by Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse, D-R.I., on whether he would advance a partisan agenda from the bench, Park said, “I just don’t see the party of the president who nominated the judge being a factor in any decision that the court renders.”

When Sen. Richard Blumenthal, D-Conn., pressed Park on his views on abortion — still then several years before the Supreme Court’s 2022 Dobbs decision — Park said, “Roe v. Wade is a landmark decision of the Supreme Court. I would follow it faithfully.”

Park’s parents, as well as Seo, were in Senate chambers for the confirmation hearing. Ok-choon recalls of the hearing, “I never experienced that much stress.” When it was over, Sen. Mike Lee, R-Utah, came over to Park’s family and told them it had gone fine.

Three months later, the Senate convened for the vote. Schumer called Park “an ideologue” and said that Park’s “principal qualification seems to be that he’s a card-carrying member of the Federalist Society.” Park was confirmed by a 52-41 vote along party lines. He had just turned 43 years old, making him one of the youngest federal appeals judges in the country.

Initially, Park says of his transition from lawyer to judge, “I missed the action of private practice: helping clients, working with a team, going to court, negotiating things,” as opposed to the “pretty monastic” life of an appeals judge where “reading and writing is the vast majority of what we do.”

Second Circuit Chief Judge Debra Livingston ’80 — nominated by President George W. Bush and confirmed in 2007 — did not know Park until the two became colleagues. Her observation has been that Park “prepares for cases with extraordinary diligence,” and that if “I’ve missed anything, he’s probably going to bring it to my attention.”

Six years into his lifetime tenure, Park says the opinion he’s most proud of is a 2020 dissent in Agudath Israel v. Cuomo. Park wrote that then-Gov. Andrew Cuomo violated the Constitution by issuing COVID-era capacity limits on houses of worship while deeming establishments such as pet shops and liquor stores “essential” and “free from any capacity limits.”

“By singling out ‘houses of worship’ for unfavorable treatment, the executive order specifically and intentionally burdens the free exercise of religion in violation of the First Amendment,” Park wrote. (The U.S. Supreme Court subsequently agreed with Park’s dissent in Roman Catholic Diocese of Brooklyn v. Cuomo.)

Park says that in writing his opinions, “clarity is the most important thing for me … . I don’t try for eloquence or clever turns of phrase. I loved reading [Justice Antonin] Scalia dissents in law school, but that’s not something I can imitate.”

Park is well aware of the political and cultural tumult of the present era.

“I’d have to agree that the judiciary is becoming more polarized politically, like everything else in society,” he says. “One of the things I ask my law clerks is ‘Where do you get your news?’ Everyone today gets their information from different sources … . Maybe I’m getting old and talking about days that never were, but it used to be we were basically taking in the world from a common starting point. But now what we think is happening or is important are just wildly different. I think that can seep into our work.”

Park says he hopes history’s assessment of the judiciary a half-century from now will be that it “remained independent.” And he hopes his fellow judges will take the approach of “viewing politically charged cases with a longer perspective. Otherwise, we risk becoming part of the problem as participants in lawfare.”

In October, Park participated in an event hosted by the Manhattan Institute, a center-right think tank focused on urban policy. One-hundred-fifty people gathered in a high-ceilinged, wood-paneled room in Midtown’s Harmonie Club for a panel discussion previewing the Supreme Court term.

Despite being the person on the panel whose position bestows on him by far the most power, Park spoke the least, preferring to ask short, pointed questions rather than giving long-winded answers. While he speaks eloquently and naturally, Park does not come off as someone who is enamored with hearing his own voice, nor does he project being someone who craves or covets the spotlight.

It is perhaps unsurprising then that Park is quick to dismiss the notion that he might someday sit on the Supreme Court and become the first Asian American to reach the nation’s high court.

“It’s not something I really think about because the possibility seems pretty remote and I’m happy where I am,” he says.

But many high-profile and influential people from across the political spectrum see Park’s Supreme Court prospects quite differently than he does.

Sahni, a Democrat, says, “I would be surprised if he weren’t being considered if there were a vacancy … . He’s a well-known judge. He comes from a significant circuit that resolves and presides over a number of very important kinds of cases. And he’s been involved in a number of cases as a lawyer that have attracted considerable attention.”

“He’s young enough and he’s surely qualified,” says Park’s Second Circuit colleague, Judge Denny Chin ’75, who was originally tapped for the judiciary by President Bill Clinton and later elevated to the appeals court by President Barack Obama. “He would need to be in the right place at the right time, but I certainly think it could happen.”

Twelve Princetonians have served on the Supreme Court, including three over the past 15 years — Alito, Sonia Sotomayor ’76, and Elena Kagan ’81.

Chin recalls that when he was nominated to the trial court in the Southern District of New York in 1994, he could count the number of Asian American federal judges on one hand, and when he was elevated to the appeals court in 2010, he was the only Asian American circuit court judge on active status in the country.

If Park reached the Supreme Court, “it would really show,” Chin says, “that we’ve come a long way.”

P.G. Sittenfeld ’07 is a freelance writer based in Cincinnati. His recent work has been published in The Washington Post, Esquire, Slate, and Outside. He can be reached at pg.sittenfeld@gmail.com.

5 Responses

Rick Mott ’73

3 Weeks AgoFair, Humanizing Portrait of Park

What Ms. Leff calls “sycophantic” I would describe as a fair and humanizing portrait of the man under the robes, which is much more that I expect from any Ivy League alumni publication these days with respect to anyone who could remotely be called conservative. Kudos to PAW. I came away with a sense of who Mr. Park is. It remains unclear to me, after reading Ms. Leff’s and Mr. Ort’s letters, what relevance Mr. Sittenfeld’s conviction and pardon have for an article about Mr. Park. To me, the article was simply a print version of an artist capturing a good likeness.

Laurel Leff ’78

2 Months AgoUndisclosed Conflict of Interest

People deserve a second chance, and I suppose there is nothing wrong with having P.G. Sittenfeld write for his alumni magazine. What is wrong is having him write a sycophantic profile of Michael Park focusing on Park’s chances of being nominated to the U.S. Supreme Court presumably by Donald Trump — the man who just happened to pardon Sittenfeld of federal corruption charges six months ago. I know the case against Sittenfeld drew much criticism, but that is hardly the point. At the very least, Sittenfeld’s pardon by Trump should have been disclosed. I am disappointed.

Editor’s note: The writer is a professor of journalism, emerita, at Northeastern University.

Jonathan Ort ’21

4 Weeks AgoSittenfeld’s Conflicts of Interest

Laurel Leff ’78 and I have written an op-ed, which describes Sittenfeld’s clear conflicts of interest and criticizes PAW’s failure to disclose them, in the Daily Prince. For reasons that the magazine is welcome to explain, PAW wouldn’t allow the hyperlink to our op-ed in this comment. The op-ed is titled “PAW omits reporter’s Supreme Court appeal — at the cost of journalistic principle.” Laurel and I remain concerned that PAW readers don’t have access to necessary context about Sittenfeld’s interests as they pertain to his reporting.

Laurence C. Day ’55

2 Months AgoA Qualified Endorsement

If Samuel Alito ’72 says Michael Park ’98 would be a great choice for the Supreme Court, I offer this retort: Since it’s coming from Alito, I would say Park would be a bad choice. Alito is one of the worst Supreme Court justices in the court’s whole history.

John Vine ’86

2 Months AgoWell Written Profile

Great story! Well written and informative. Clearly, Michael Park is a very bright man who also appears to have a good sense of humor as well as decent dance moves.