Michelle Lerner ’93 Explores Grief in Her First Novel

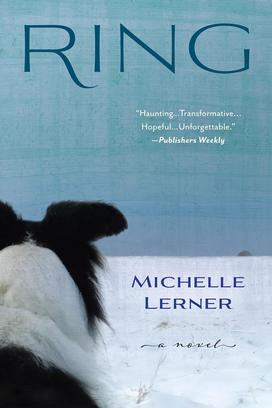

The Book: Ring (Bancroft Press) is a tale of grief and healing. Lee, a middle-aged, nonbinary Midwesterner mourns the loss of their daughter. In a snowy sanctuary for the dying, Lee finds unexpected comfort through Ring, a seemingly ordinary dog assisting a terminally ill man. Lee meets and befriends others at the sanctuary, confronting loss, mindfulness, and suicide together. Ring is a deeply moving and emotional story about the human experience and finding closure.

The author: Michelle Lerner ’93 earned her undergraduate degree from Princeton in anthropology and went on to receive an MFA in poetry from The New School. In addition to Ring, she is also the author of Protection, a poetry chapbook that was published in 2021. Her writing has appeared in VQR, Lips, and the Paterson Literary Review, among other publications. Lerner’s poems have been selected as finalists for various awards including the Book Pipeline Unpublished Contest and the Bridge Eight Fiction Prize. She also directs the Laura Boss Poetry Foundation.

Excerpt:

Union Station

Union Station in Winnipeg was huge. Entering through the glass doors at the bottom of the concrete facade, I had the sense of walking through a portal. The space inside was open, round, and clean, with a high circular skylight that looked like a miniature firmament sitting on the globe of the waiting room.

I don’t know what I’d been expecting, but I suppose something quiet and discreet. Something out of the way. Winnipeg was not that place.

I had a few hours before the train left for Churchill. There were no empty benches, and I was so exhausted I considered lying down on the floor. Instead, I sat on a bench occupied only by an elderly woman, in the hope that, once she left, I could lie down or at least rest there against my backpack.

On the plane ride here, I’d felt no fear, at least not of flying. I had always been so scared of it, until the trip last summer to claim Rachel’s body. On that flight, I had barely noticed being in the air. But I hadn’t been sure if that was just due to the shock, or what to expect on the flight yesterday from Madison to Winnipeg. So I’d carried my bottle of Xanax in my pocket, planning to take as much as I needed before the final leg of my trip to Attawapiskat, at which point I would throw away the rest — the Seven Pillars Society doesn’t allow tranquilizers.

This trip was the first time I’d left the apartment since the funeral. In truth, I’d hardly been out of bed in months. I couldn’t even find the energy to stand in the shower, had resorted to getting into a bathtub when required by exasperated friends who stopped by to try to get food into my mouth and stench off my body. What I remembered most about the months after Rachel’s death was the olive and white of the apartment walls, and the rough woven texture of the mustard-colored curtains in the bedroom. The feel of the comforter between my fingers as I pulled it over my skin, often as a shield against Susan’s constant repetition of all the minutiae we knew about Rachel’s last day. I’d begun taking the Xanax all the time; it was no longer just for flying.

But yesterday, on the flight to Winnipeg, I’d found I didn’t need it. Fear of flying has to do with fear of death. After Rachel died, I guess this fear just disappeared. When the plane landed, I tossed the pills.

It didn’t take long for me to realize that was a mistake. After the flight, as I lay in the hotel bed, unable to sleep, I remembered that you’re not supposed to suddenly stop taking medication like that, that it has to be tapered. That it can even be dangerous to stop cold turkey.

There was nothing I could do about it at that point.

I was already used to being awake on and off during the night. I hadn’t had a normal circadian rhythm since Rachel’s death. I was rarely awake or asleep more than three or four hours in a row. Though I’d lived through many days since my daughter died, I couldn’t admit they were of the same nature as when she was alive — similar length, similar weather. That I was moving through the doors of the same successive hours as the people I saw walking by the window of my apartment. The days seemed to pass through me rather than the other way around.

I slept, drug-induced, at odd times. The hours stood still on top of me, little demons with weights pinning me to the bed. The stillness wasn’t natural, but it was complete. Somehow my chest had continued to move, and air entered my lungs — my only source of amazement for months.

But in the hotel room last night, without the Xanax, the feeling was different. It was a clearer-headed, pulse-racing awakeness that was not just an interlude between sleep, but something actively opposed to sleep. I lay there at least half the night with my heart pounding in my chest.

The snow outside the window had calmed me. It was dark, but I could see it coming down, feathery and light against the glass. There was a bright blur in the sky that could only have been the moon behind clouds.

The benefit of not falling asleep had been avoiding the moments after waking, when I’d usually forget, and then remember.

Rachel

Rachel was a clear brook, transparent, deep. Every pebble dropped straight to her core.

She was the purest metal, conducting every spark that touched her, taking everything in and passing on the charge.

Once when she was nine, she told her teacher she couldn’t concentrate because of singing outside the window. She was sent to the nurse, then the counselor, then home with a note that she needed a psychiatric evaluation. But, she insisted, someone really was singing, loudly. She took me there the next day, to the tired grass below the window of her classroom. Bending down, she held out her arms with her hands on the ground while a cicada climbed up her shirt, trilling.

There was before Rachel, and there was after Rachel. There were 23 years in between. The 23 years that were Rachel.

When they found her car in the desert, Susan was convinced Border Patrol was responsible for her death. Rachel was working with a grassroots group driving food and water to migrants, and was proud of her work. Then we stopped hearing from her. Then they found her car. Then they found her. The investigation by local law enforcement found no evidence of anyone else’s involvement and ruled it an accident or suicide, with heat exhaustion the cause of death. That Rachel either had been just walked out into the desert alone as a way to kill herself.

Susan didn’t believe any of it, was sure the investigation was tainted because of Border Control’s likely involvement, that Rachel wouldn’t have done this to herself, that she had left no note, that she was experienced in the desert and the desert heat and couldn’t possibly have been so careless as to strand herself and succumb to heat exhaustion.

It’s not that I thought Susan was wrong. I just wasn’t sure she was right and I had no energy to fight, no sense of what could possibly be done since the essential event could not be changed or set right. Susan flailed and raged, took my resignation about the investigation’s conclusions and my shriveling withdrawal as an offense, contacted lawyers and human rights organizations. There was always a new suggestion of where to look, who to contact, what to ask, but none of it ever led to any answers.

She pursued every detail, wanted to talk through it every minute of every day, over and over, shuffling papers on her lap, rereading out loud each detail of the same reports, asking me the same questions. While she talked, I lay in bed with the demons on top of me, facing the wall. None of it came to anything. Six months after her death, there was no more information than in the first days after she was found.

It’s hard to explain, but by that time it almost didn’t matter what had actually happened; I was devastated to the marrow of my bones. There was nothing left. She was gone. She had walked through some door, willingly or unwillingly. The need to understand why eventually ran itself aground in the stunned silence inside my head. There were no longer meaningful points of view, things to comprehend or argue about. There were just ideas like piles of sand that people moved from here to there, separated out into smaller piles, stood in front of, gave names to, fought about. I would say I stepped around them, except I hardly got out of bed.

Because, really, the piles were made of quicksand. Miniscule, nondescript, meaningless spots of quicksand. All around my bed. Susan and the other people entering the apartment dragged them in. My bed was solid, so I stayed there and looked at the ceiling while they talked in the other rooms. I don’t remember if I got up when Susan moved her last box out the door. To be honest, I don’t really remember her leaving.

Sometimes I try to think of Susan before and during Rachel. Because it doesn’t seem fair to only think about the way she acted after. But every time I try, all I see is the drawn skin on her face, the plowed furrows on her forehead, the lines at the sides of her eyes and mouth. For every rung I climbed down inside myself after Rachel died, Susan climbed up and out, anger emanating from her the way heat rises off the pavement in August.

There must have been a moment when we crossed each other’s latitude. Maybe it was the day they found Rachel’s body, since I remember Susan’s fingers gripping the flesh of my sides. I know she wailed, but in my memory, she was silent, her mouth large and moving without sound, her fingers gripping me tight.

After that we lived in two different climates. I’ve been told everyone grieves differently. Which presupposes that each person is still there, intact in their personhood and personality, engaging in the action of grieving as an experience or a process. But I think grief takes its own form as it consumes a person from the inside, devouring whatever preexisted.

How it looks from the outside depends on how fast it does the devouring, how completely, and with what kind of energy. By the end, Susan and I were just vessels for grief, its fingers reaching out through our previously human bodies. In Susan’s body, the grief was hot and could not stop running. In me, it was a glacier, and the ice filling me became me. Cold to the bone, there was too little of me remaining to stand in her way as she left.

Excerpted from Ring by Michelle Lerner. Copyright © 2025 and published by Bancroft Press. Reprinted with permission of the author.

Reviews:

“Unique and powerful, Ring is a stunning, hypnotic book.” — Ellen Pall, author of Must Read Well

No responses yet