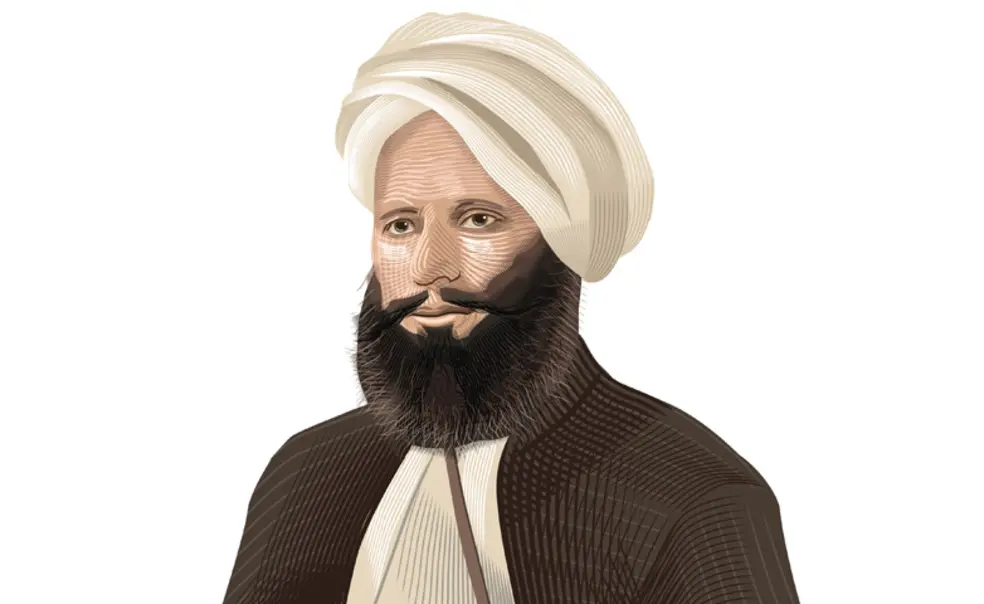

A Missionary Who Provoked an International Diplomatic Crisis

Rev. Jonas King h*1832

On Oct. 20, 1836, two foreign applicants arrived on the doorstep of Nassau Hall seeking a Princeton education. Luke Oeconomos 1840 and Constantine Menaeos 1840 hailed from Greece, a country that had just won its independence from the Ottoman Empire. Evidently, philhellenic feeling was strong in New Jersey at that time, as the countrymen of Homer, Xenophon, and Plato were admitted on full scholarship, becoming two of the first international students at Princeton.

Two years later, a third Greek student, Constantine’s cousin Anastasius Menaeos 1840, joined them. In his book The College of New Jersey, President John Maclean Jr. 1816 wrote, “They were young men of good moral character, good talents, and good scholarship, and proved themselves worthy of the assistance given to them.”

More notorious, however, was the story of the man who had brought them to Princeton, the Rev. Jonas King h*1832, whose controversial missionary activities in Greece led to a major early episode in American gunboat diplomacy.

A Congregationalist missionary from Massachusetts, King attended seminary at Andover. After leading a ministry in South Carolina, King returned north to teach Arabic and ancient Greek at Amherst College. There, he became involved with the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM), then the largest missionary organization in the U.S. and a precursor of other major international aid organizations such as the YMCA and Red Cross. In 1822, after a stint handing out Bibles in Ottoman Palestine, King traveled to Smyrna and Anatolia and learned the modern Greek language.

With the Greek war of independence against the Ottomans underway, King went back to the U.S. to raise funds for the Hellenic cause, part of a broader international coalition then lobbying to support the revolution. In 1828, with independence at hand, King returned to Greece and observed the impoverished situation of the people there, motivating his next initiative. As quoted by historian Angelo Repousis, King wrote that “I hear a voice soliciting schools, books, and instruction.” He added, “How noble, how glorious, would it be for the American republic to be the restorer of learning in Greece.”

King visited Princeton frequently during his stints stateside, and in 1832 he was rewarded with an honorary doctorate bestowed by James Carnahan 1800, a fierce pro-Protestant. And with the financial backing of the ABCFM, King founded several schools of various levels (including one girls’ school) in Athens and the surrounding islands. More than 250 students were in attendance, learning subjects such as geography, algebra, and, well, the Bible. That’s because King didn’t just want to educate the Greeks. He wanted to convert them.

Most Greeks belonged to the Orthodox Church. According to Repousis, “An encouraged King wrote that the day would soon come when the Greek church ‘will very much resemble our own, or the Presbyterian.’”

As King’s attempts to instill Protestant views — such as castigating the veneration of icons — among Orthodox Greeks became widely known, his Athenian critics lashed out, calling him “the Devil’s apostle.” In 1845, the Greek Synod even went so far as to excommunicate him, even though he wasn’t actually a member of their faith. Seven years later, with King persisting in his activities, matters came to a head and the Greek government charged him with blasphemy, convicting him after only six hours of deliberation.

In the U.S., King’s ensuing imprisonment in Greece was received with outrage in the press and in ecclesiastical communities. At the time, Secretary of State Daniel Webster was eyeing a presidential run and wanted to project strength. Webster dispatched diplomat George Marsh aboard an American warship to conduct his own investigation in Athens. Though Marsh found evidence of persecution against King, his admonitions failed to secure King’s freedom. The missionary was finally released from prison in 1855 after the U.S. indemnified Greece for land expropriated from King’s holdings in Athens.

Despite his ordeal, King remained in Greece until his death. Two of his followers founded the Greek Evangelical Church in Athens, an institution that remains active in the Greek capital today, though to little avail — Greece remains 90% Orthodox.

No responses yet