Molecular Biology: Dad, Interrupted

New DNA research exposes cellular effects of childhood trauma

It’s often been said that children who experience early trauma grow up faster. New evidence from molecular biologist Daniel Notterman shows that this might literally be true — all the way down to a child’s DNA. Notterman, who is also a pediatrician, studies the complex interactions between genetics and environment. “I see how disease is often related as much to the underlying genetic substrate as to the lives that children live,” he says. “I want to understand how the environment literally gets under your skin.”

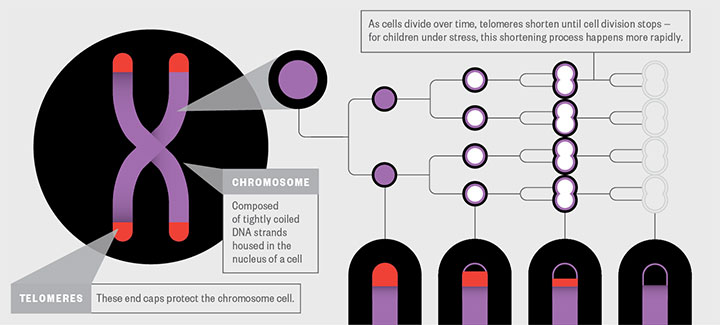

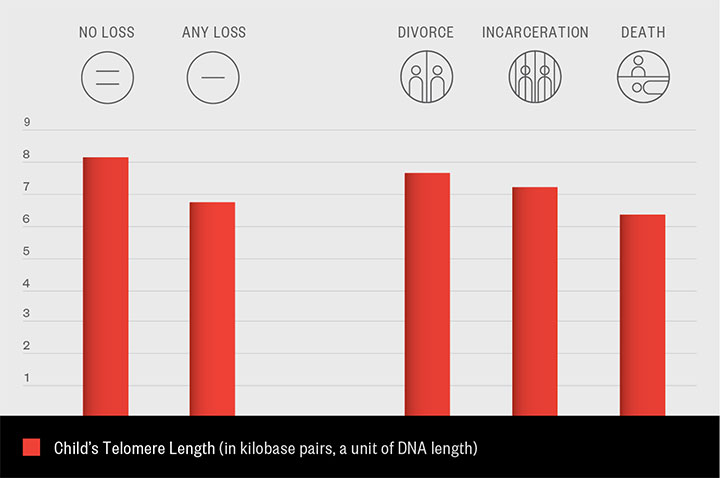

Notterman’s latest study looks at one of the most devastating traumas to befall a child: the loss of a parent. Studies have associated parental loss with difficulties in school, poor social relationships with peers, and mental-health and behavioral problems ranging from depression to aggression. Working with Princeton sociologist Sara McLanahan and Columbia sociologist Irwin Garfinkel, who have conducted a long-term study of at-risk children, Notterman’s lab examined DNA samples from 2,420 9-year-old children in 20 American cities. He found a clear biological difference in those who had lost a father: a shortening of the length of vital sequences of DNA at the end of their chromosomes, called telomeres.Often compared to the plastic caps on the end of our shoelaces, telomeres prevent the ends of DNA from fraying. Once telomeres become too short, cells stop dividing, weakening the immune system and other important inner functions, hastening the aging process. On average, Notterman found that children who had lost a father through death, incarceration, or divorce had telomeres that were 14 percent shorter than those who hadn’t. (While the group Notterman examined didn’t include enough children who had lost mothers to draw conclusions, he speculates the effect would be similar.)

Telomeres Explained

Not all fatherless children were affected the same way. Those who had restricted access to their fathers because of separation or divorce showed only a 6 percent drop in telomere length, and the study concluded that most of that decrease could be correlated to a loss in family income. “That [finding] suggests that where there is separation but still contact, you could mitigate the effects by targeted resource allocations to these families,” says Notterman. On the other hand, those who had lost fathers to jail or death showed 10 percent and 16 percent shortening, respectively.

In those cases, says Notterman, the loss was so overwhelming that favorable economic circumstances couldn’t make up for it. “Those children might need other forms of social support like a different father figure in their lives such as a grandparent or a Big Brother, as well as some form of therapy,” he says. Even among children who had lost a father, however, there was significant variation in telomere length, depending on their underlying genetics. Identifying those children who seem particularly vulnerable after a trauma, Notterman says, could help doctors target children who are most at-risk with interventions, before they develop health complications later in life.

2 Responses

George C. Denniston, M.D. ’55

8 Years AgoOutlawing a Trauma

Published online Oct. 23, 2017

The article “Dad, Interrupted” (Life of the Mind, Sept. 13) documents the loss of telomeres due to early childhood trauma, which hastens the aging process. Partial penile amputation, euphemistically called circumcision, is an early childhood trauma for millions of American men. If there were no religious implications, this procedure, carried out by American doctors, would be understood by all as an atrocity – a cruel, senseless act. Circumcision of males is illegal in the United States due to the Female Genital Mutilation Act of 1997 and the Fourteenth Amendment, which applies it to all persons, but there is no enforcement.

Circumcision is a massive human-rights violation, and it is time that we outlaw it. Those of the Jewish faith have a way out: Brit Shalom (see www.CelebrantsofBritShalom), where more than 150 rabbis are willing to perform the ceremony without the cutting. For more on why this behavior should not exist, please go to YouTube, type in my first and last name, and listen.

Christine Futia ’79

8 Years AgoThe Role of Telomeres

I was so delighted to read about Professor Daniel Notterman’s research on telomeres (Life of the Mind, Sept. 13). My son was born with dyskeratosis congenita (DC), a rare and fatal disorder caused by exceptionally short telomeres. I often use the “shoelace cap” analogy to explain how telomeres act to keep our DNA stable while our cells divide. Often, bone-marrow failure is the first symptom of DC, since the blood-making cells divide faster than any others in our body. A person with DC is a naturally occurring example of what happens as we age and our telomeres become shorter and shorter.

My son passed away in September at the age of 22 from the combined effects of aplastic anemia, myelodysplastic syndrome, and pulmonary fibrosis. His genetic material is part of a research study at NIH that will ultimately help us understand the role telomeres play in the common diseases of old age, including cancer, osteoporosis, fibrosis, and organ failure. I’ll never know if my son’s telomeres were affected by both his genetic inheritance and life experiences, but I do note that he was separated from his birth mother on his first day of life and grieved her throughout his days.