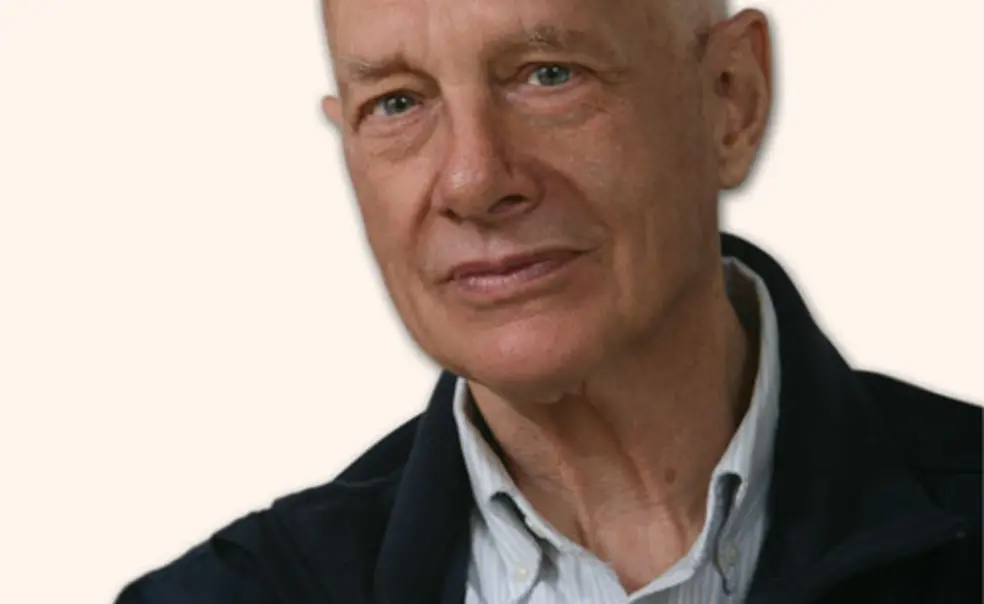

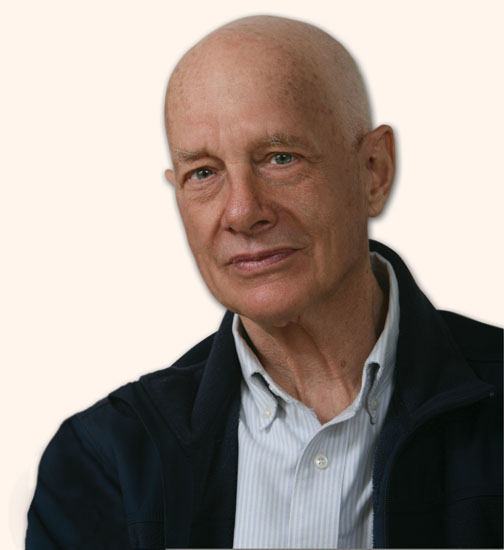

A moment with ... John Gager, on being a Freedom Rider

In the spring and summer of 1961, scores of men and women participated in protests against racial discrimination by riding buses across the segregated South. On June 7–8, 1961, one of those “Freedom Riders” was Yale Divinity School student John Gager, who would spend 38 years on the Princeton faculty before retiring in 2006 as the William H. Danforth Professor of Religion. Gager looked back on his Freedom Ride from Atlanta to Jackson, Miss., and on the ways in which the country has changed during the past half-century.

What made you decide to join the Freedom Riders?

My involvement in the civil-rights movement really took off during my first year at Yale Divinity School. Yale was an important center in the movement at the time because the chaplain was William Sloane Coffin, who was a huge inspiration for me. When Coffin came back from his own Freedom Ride in Alabama, he urged more of us to get involved. Coffin said that this is what we were called to do. So I and a few others from Yale, mostly graduate students and divinity students, decided that we would go.

How were you received in Atlanta?

We [Gager and his wife] stayed with a black pastor and his family and got a sense of what it was like to be a black family in the Deep South. We were told that being a white couple staying in a black home put us and them in danger. So we needed to be careful about where we went and with whom. The black people we met didn’t talk a lot about segregation, even though they were resisting against it. Segregation was simply the way life was for them. But for most of us, it was really alien territory.

The evening before our Freedom Ride began, three or four of us went to services at a black church. We were sitting up in the balcony, and when the choir started to sing, the pastor said, “Wait. You white folks up there in the balcony. I know you can’t sing like the choir, but I want to hear your voices here today!” That was his way of including us. It was an incredibly heartwarming experience for us and revelatory, too, of hospitality and graciousness. What is terribly ironic is that if we had gone down to Atlanta under completely different conditions and been guests in the white community, we probably would have been received in the same way.

Did you have any training in what to expect and how to react?

It was very brief. We were grown-ups — I was 23 — and the people in the SCLC [Southern Christian Leadership Conference] who organized the rides had some experience doing this, so they knew exactly what was going to happen. We were going to step off the bus in Jackson, the blacks were going to go to the “Whites Only” waiting room, and the whites were going to go to the “Colored Only” waiting room. The police would be there. We’d be arrested, booked, and put into a jail cell. We didn’t need much training. We were all asked to commit ourselves to nonviolence, and we did, but we were also told that there wasn’t going to be any violence because the police and the Justice Department did not want any violence. The police had the Jackson bus terminal cordoned off when our bus arrived, so all the potential troublemakers had been kept well away.

After it was over, we were all sitting on the airplane that was going to take us back to Atlanta, blacks and whites together. A man walked down the aisle, and I remember him saying, “Did y’all enjoy your stay in Jackson?” He was a member of the city council, but he did not seem bitter. It was not clear what he thought of the disturbance that the Freedom Rides had caused, and the negative attention that had been brought to Jackson and the South, but he seemed to be looking forward and could imagine a day when things would be different.

You did not ride directly from Atlanta to Jackson. Why?

After a Freedom Ride bus had been burned in Alabama days earlier, [U.S. District Court] Judge Frank Johnson enjoined the Freedom Riders from riding through that state because there was too great a chance of a disturbance and the authorities could not protect them. So we got on our buses in Atlanta, but when we reached the state line we were diverted up to Nashville, Tenn., where we changed buses and went on to Jackson.

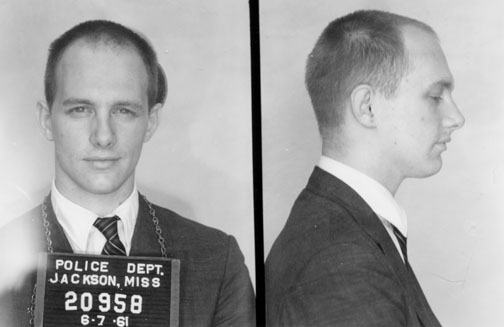

When we arrived in Jackson, we did what we had planned to do — break the law by going into the segregated waiting rooms — and from there it was fairly straightforward. We were arrested for disturbing the peace, which was a complete nonevent. We did not resist — we had been told that resisting was not the point — and then we were processed and fingerprinted, and our mug shots were taken. No one spat on us or roughed us up or called us any names. The white police and city officials in Jackson had worked out their side of the thing, too.

Initially, we were put in a large cell, blacks and whites together, which was a huge thing for them to do. They couldn’t imagine how white people could be with black people. A short time later, as more and more Freedom Riders arrived in Jackson on other buses and were arrested, they ran out of jail space. That was part of our strategy, to flood the system. So at that point, the Jackson police decided that the only option was to ship us off to the state penitentiary in Parchman. There they made a conscious decision to segregate us from the rest of the prison population, for two reasons: They were fairly certain that the white inmates would treat us badly; and they did not want us infecting the black population with stories of resistance, freedom, and equality. So they put us in the high-security section of the prison, one person per cell, with our food put through a slot in the door on a tin tray. We were on a long corridor, so we couldn’t see one another, so all we could do was speak and sing, spirituals mostly.

Eventually, the SCLC posted our bail and we were released. We never went back for our trials, though, because the SCLC ran out of money to pay the lawyers, so we pleaded nolo contendere. I have never had occasion to go back to Jackson, although I have no feelings of animosity toward the place.

What did the experience mean to you?

Without that experience, I certainly would not have played the role that I did on this campus during the Vietnam protests. I think that it also affected my teaching, in prompting me to get students to challenge their fundamental assumptions and not take the world as it is as a necessary given. I tried to get them to see that it could be something other, and by human action.

Most of my scholarly work has been on relations between Christians and Jews in the early centuries. I have written a book about Christianity and its influence on culture during that period, and I place a great deal of emphasis on its role in creating and sustaining anti-Semitism. Recently, I have looked at a body of Jewish work in those early centuries that could be described as a pushback against Christian domination and oppression. I see that Jewish pushback against Christian domination as being not unlike the pushback by blacks against white domination in the South, and I suspect that is why I was drawn to it.

What did the Freedom Rides achieve?

There is no doubt that the Freedom Rides helped bring about great changes, but to be poor and black in Mississippi is still a terrible thing. Even in the North, we still live in a largely segregated society, especially along economic lines.

But I have always held the view that radical political activity creates space in which people are free to think and act in ways they never have before. By pushing the boundaries, the civil-rights protests opened up space where people could think and act differently. The greatest changes come about not through changes in law, but in attitudes. So I like to think that the civil-rights movement simply showed blacks and whites together — on buses, in marches, in churches — in ways that people had not thought possible.

Would students today be as likely to participate in something like the Freedom Rides?

I see that there are students who are eager to participate in activities that they see as contributing to the well-being of people. The Community Action program [a Princeton community-service program for freshmen], for example, takes incoming students to Trenton, where they engage in a number of service projects. My sense is that if something like the civil-rights issue were to arise again, there would be students participating. I don’t think that has changed.

— Interview conducted and condensed by Mark F. Bernstein ’83

No responses yet