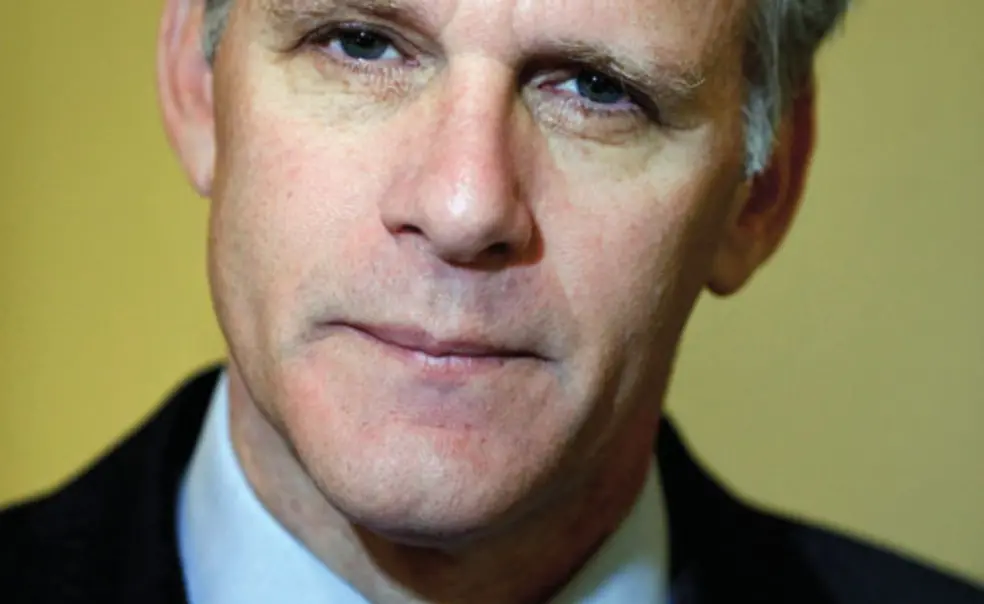

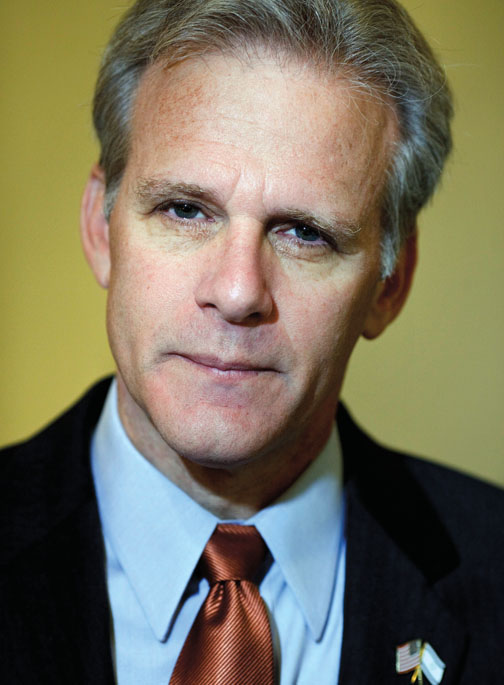

A moment with ... Michael Oren *84 *86, on representing Israel

Last year, Michael Oren *84 *86 — who was raised in New Jersey and later moved to Israel — became Israeli ambassador to the United States, giving up his U.S. citizenship. He took an untraditional path to his new job: Though he had worked for Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin in the 1990s, he was not a career diplomat, but a historian — one who had studied with such Princeton giants as Charles Issawi and Bernard Lewis. Oren spoke with PAW at the Israeli embassy in Washington in early March — days before a trip to Israel by Vice President Joe Biden that exposed a rift between the two allies over construction in East Jerusalem. Oren followed up with a telephone interview April 15.

You’ve said that the United States and Israel agree on about 98.9 percent of things. With relatively new governments in both nations, has that changed?

There is a difference of emphasis and a somewhat different list of priorities. For example, the Obama administration made a more public demand for a settlement construction freeze. But by and large the policies are similar. The Bush administration and the Obama administration, and the previous Israeli government and the current Israeli government, have all signed on to the two-state solution. The Obama administration has been much more activist. And we welcome the activism.

We have seen many times where the U.S. and Israel disagreed on features of one another’s policies — the American sale of AWACS jets to Saudi Arabia in the 1980s, and with Eisenhower in the Suez crisis in the 1950s. This is a difference about a policy — a core policy — but it’s not a departure from longstanding American or Israeli policy, just a matter of emphasis.

Though there’s strong support for Israel among Jewish Americans, that community is not monolithic in its views about Israeli policies.

No, it is not! (Laughs) Some people say we should be conceding more; some people say we are conceding too much. My job is to seek the common denominators.

You got much attention for refusing to speak to J Street [a Jewish group with liberal views on Israel, founded by Jeremy Ben-Ami ’84]. What are your feelings about that group?

I didn’t refuse to speak to them; I just declined an invitation to appear at their convention. I decline about 10 of those invitations every day. In fact, we always had a dialogue going with J Street. We had some concerns about some of J Street’s policies, which we thought had an impact on Israel’s security interests, but J Street has since moved in ways that to my mind bring them within the mainstream. There was never a boycott of them, and there won’t be, either.

You were heckled at a recent talk at the University of California, Irvine, and several people were arrested. Is Israel losing the public-relations war among young people?

I don’t think we’re losing it. But that doesn’t mean campuses don’t pose formidable challenges to Israel. First is the challenge of speakers on campus — anti-Israel speakers, or pro-Israel speakers who come on campus and are heckled. Then there’s trying to create a balance in the classroom. There is a widening corpus of academic books that present perspectives critical of Israel, but a small subset of books that I would call fair to Israel. Someone who has not a pro-Israel perspective but a fair perspective on Israel will have a hard time getting tenure in a Middle East studies department on an American campus. Over the last few years I’ve devoted a substantial segment of my time to teaching in American universities in an attempt to redress the imbalance.

How does being a historian inform your current job?

I approach every subject with a historical context and a historical consciousness. There’s a school of thought that insists that unqualified support for Israel has been the cornerstone of American foreign policy since 1948. Even a cursory examination of the history will tell you that that’s utterly without foundation. There was no strategic relationship between Israel and the United States until the aftermath of the 1967 war. There were times when the so-called Israel lobby proved incapable of altering American policy. It is an anomalous alliance, in that one member of the alliance doesn’t recognize the capital of the other. If the Israel lobby is so powerful, why can’t they bring that about? And the status of Jerusalem, by the way, falls into that 1.1 percent of things we don’t agree about.

I was having a conversation with the board of a popular publication in the United States. They asked me, ‘Do you really think the Palestinians and the Israelis can ever resolve their differences over the West Bank and get past their irredentist claims?’ I fired back, ‘Well, how many Frenchmen and Germans do you think today are willing to fight and die for Alsace?’ And yet, millions did at one point. I do think it’s possible.

— Interview conducted and condensed by Louis Jacobson ’92

No responses yet