If you think it’s a pain to move, just picture rehoming tens of thousands of priceless objects, and then moving them back. Not only that, the Princeton University Art Museum had to contend with COVID restrictions, fragile research, and sleeping students. But the end is near and so is the opening of a new multimillion-dollar facility that has been years in the making.

The new museum is hard to miss, smack dab in the center of campus between Prospect House and Dod Hall. At 146,000 square feet, it doubles the gallery and education space of the previous museum, and that’s not including the gift shop and restaurant. In addition, to support this massive expansion, the Princeton University Art Museum (PUAM) is hiring 65 staff members.

Museum officials are sure the result will be worth the wait, and come Oct. 31, the community will be welcomed in to see for themselves (for free, as always) for a 24-hour open house and during regular business hours afterward.

But one thing that won’t be on display — or at least made obvious — is the planning and meticulous work that went into building the museum and curating it in a way that is just right. The project broke ground in the summer of 2021 and created a virtual black hole in the middle of campus, and even now that most of the fences have come down, the enormous and somewhat imposing stone, bronze, and aluminum walls don’t give much away. With a 117,000-piece collection, including items that date back 5,000 years, it’s still a mystery as to what exactly viewers will see when they step inside.

PAW was given two sneak peeks, first in early February and then in late March, to see how the museum is coming together and understand the work of moving in. Let’s go behind those daunting walls.

When PUAM’s director James Steward found out a new building was planned, he was given two primary goals by Princeton’s administration: to build a museum that would meet the University’s needs for “at least the next generation,” and “function well for a hundred years,” he says.

It was an intimidating task, for which the University hired Adjaye Associates, designers of the Smithsonian Museum of African American History, among other notable projects, and Cooper Robertson, who served as executive architect, and who a PUAM press release stated is “acknowledged as among the foremost museum planning and design firms in the country.”

It was unclear at first whether the new museum would sit on the same site as the old one, which was important to Steward. “The symbolic value of having a museum of this magnitude and importance in the physical heart of our historic campus says a lot about, I think, what Princeton is and what it wants to be.”

Steward promises he won’t mind when someone passes through the hallways to get to class or stops to sit on a bench and use their phone, as both are still encounters with art that “perhaps then invites you, tricks you, to want to have a deeper experience.”

Once the location was confirmed, the old museum, which opened in 1966, was scheduled to close in 2021. According to Steward, “moving collections of this scale is a herculean act in and of itself,” not to mention additional difficulties that came along with the pandemic, which moved the timeline up. About 56,000 pieces of art had to be deinstalled while staff socially distanced. Roughly 245 shipments of 5,000 boxes and crates later, the art had left the building.

Demolition led to the twin discoveries of asbestos in the old museum — even more than had been anticipated — and that a vapor barrier meant to reduce water had failed in Marquand Library, which was given a facelift and is incorporated into the new museum. Meanwhile, all of this took place as PUAM still operated two galleries in town — Art@Bainbridge, which will continue to host special exhibitions, and Art on Hulfish, which closed this January.

Construction presented challenges. For example, trucks carrying 60-foot steel beams to the site could not navigate the turning radius on Faculty Road. “We had to basically remake that traffic circle and lower it into the ground … in order to facilitate the movement of all this material into a landlocked environment,” Steward said during this year’s Wintersession.

Construction was completed last year, and in the fall, a few of the larger pieces were embedded into the floors and walls. In January, the move-in began in earnest with the museum welcoming the rest of the art, a reunion Steward admitted on Alumni Day this year led him to “shed more than a couple of tears.”

Just transporting art back into the building from storage required years of planning and the utmost care.

In addition to space onsite, PUAM operates two storage facilities — for a total of about 27,500 square feet of storage space — that have humidity and temperature controls (which generally match conditions at the museum), dim lighting, a fire suppression system, and human and systems security.

At Wintersession, Steward told the audience that PUAM “will be more dependent” on off-site storage “than we ever were prior to construction.” That’s in part due to the growth of the collection; the museum acquires more than 1,000 objects per year. Only about 5% of PUAM’s collection will be on display at any given time in the new building, but in the old museum, that number hovered around 2%.

In storage, items are selected for display and then packed one gallery at a time according to size, sometimes in customized crates, sometimes in boxes lined with Tyvek or Volara, synthetic coverings that protect the exterior of a house during construction.

“We don’t pack anything in peanuts or tissue,” says Virginia Pifko, senior collections manager. “Everything is secured inside the container so it won’t move, but it’s not being touched by anything that can degrade it or deteriorate it.”

PUAM staff work in tandem with an unnamed (for security reasons) fine arts art shipper based in the tristate area. The trucks are required to have air ride — a smooth suspension system that uses air-filled bags — a lift gate, and a climate-control system. And there are always two drivers for safety reasons.

“We’re always making sure art is comfortable and safe no matter where it is, if it’s in a truck, if it’s on a shelf, if it’s in a gallery,” says Alexia Hughes, chief registrar and manager of collections services.

Items in transit are checked by registrars a minimum of six times, sometimes up to 10.

“This is basically how art moves anyway for exhibitions or loans. … The quantity is on steroids, but it’s a part of what you do,” said Hughes.

The largest painting in PUAM’s collection, Ellen Gallagher’s Blubber, was a special challenge. It was 12 ½ feet tall by 16 ⅔ feet long once crated and required a special truck.

Remarkably, as of late March, no objects had been lost or damaged during the move, and about half of the art that will be on display was already packed up in storage, awaiting delivery.

Even once the art is installed, staff still have to manage empty crates and boxes so they can be reused. For Pifko, that turned out to be “the biggest surprise … because it’s almost the same amount of work as moving the artwork.”

During my two visits, I was greeted by temporary flooring (to protect the new construction underneath), rows of paint cans lined up along bare walls, large trash bins scattered among hallways, and lots and lots and lots of boxes. There was some art too, though most of it was not display-ready. I observed one sculpture divided into three boxes.

It felt intrusive to see the museum this way — a rare sight, as the staff said more than a few times. When visiting for the second time, about 20% to 25% of the art that will be displayed on opening day had been installed.

We started on the first floor, which is home to the gift shop; the Grand Hall, which can be transformed to suit a variety of purposes; and the Welcome Gallery, which will rotate exhibitions annually. The rest of the galleries are on the second floor and will rotate more frequently. Steward says the new layout will help avoid the “upstairs-downstairs” problem the last building had.

“We used to estimate that probably something like 40% of our visitors never even made their way to those lower-level galleries because it wasn’t necessarily obvious to them that they were there,” he says.

Determining the placement of art in the new building was a collaborative effort that took into account the building’s design, curatorial vision and values, and PUAM’s teaching and research mission. The museum had to contend with “a very small number” of works with stipulations attached — gifts received on the condition that they had to be installed — so according to Steward, when choosing what to display, “the key considerations have been what is needed for teaching and research.”

At the top of the Grand Stair, viewers will find a somewhat unexpected selection of pieces from different regions and time periods in a space known informally as the orientation gallery. “We wanted there to be a moment in the building early in the sequence of galleries where a visitor would be introduced to the sheer range of what’s to be found in our collections. So, rather than thinking we were only a museum of x, y, or z, you’re provoked to realize it’s all of the above,” says Steward.

That’s part of PUAM’s mission to create dialogue within the collection in ways that might be surprising.

The allocation of gallery space was also rebalanced from the old museum to respond to “teaching needs and the growth of the collections, and a variety of other considerations,” according to Steward’s remarks at Wintersession. For example, African art will occupy seven times the space it had in the old building, while the ancient Mediterranean section will be smaller than before.

Several pieces were commissioned for the new museum, according to a press release, including a monumental wall relief by Nick Cave incorporated into the entrance court. A sculpture by Diana Al-Hadid and another by Tuan Andrew Nguyen will be displayed, as well as a painting by Jane Irish that will grace the ceiling of an intimate viewing room.

Two additional pieces out of the 7,000 that will be on display were acquired for specific museum sites. A bronze sculpture by Rose B. Simpson on the south terrace that can be seen from the ground overlooking campus was installed in March. A glazed ceramic piece by Jun Kaneko was selected for “an area in the northeast of the building,” according to a press release.

The museum will also display several pieces for the first time that were acquired during the five-year closure, including El Manto Negro by Teresa Margolles, exciting staff who have “just seen it in storage in boxes on the shelf,” says Pifko.

“With its 1,600 burnished ceramic tiles, that will be a feat of installation,” Juliana Ochs Dweck, chief curator, wrote via email.

New special exhibitions are planned every three to four months, and Steward says after six months, the rest of the collection will be changed frequently too.

For the first time, PUAM will offer food and beverages thanks to a new restaurant, Mosaic, which will share the third floor with offices. Although some details are still in flux, Steward expects Mosaic to serve coffee and pastries in the morning, lunch and snacks in the afternoon, and around 80 annual prebooked dinners with themes correlating to the museum’s collections.

Steward picked the name Mosaic because “I kind of love the way the word, in a sense, captures the idea of making something whole out of its parts,” he says with a laugh. “Because I think you could think of that as a metaphor for what a chef puts on a plate, as well as for the kind of art we collect in the building.”

Another feature of the new museum is a larger education center. The more than 12,000-square-foot space includes two creativity labs for hands-on learning, six object study classrooms, an auditorium, and two seminar rooms. There is also a two-level conservation studio for preserving and investigating art.

“A set of conservation studios is a complete game changer at Princeton in that we’ll finally be able to care for the whole of our collections on site,” Steward said at Alumni Day.

There will also be familiar favorites on display. The portrait of George Washington by Charles Willson Peale was the “first work of art installed in our new museum, which seemed remarkably fitting,” Steward said at Alumni Day. It has been in the museum’s collections for longer than any other work of art, having been commissioned by the University’s Board of Trustees in 1783.

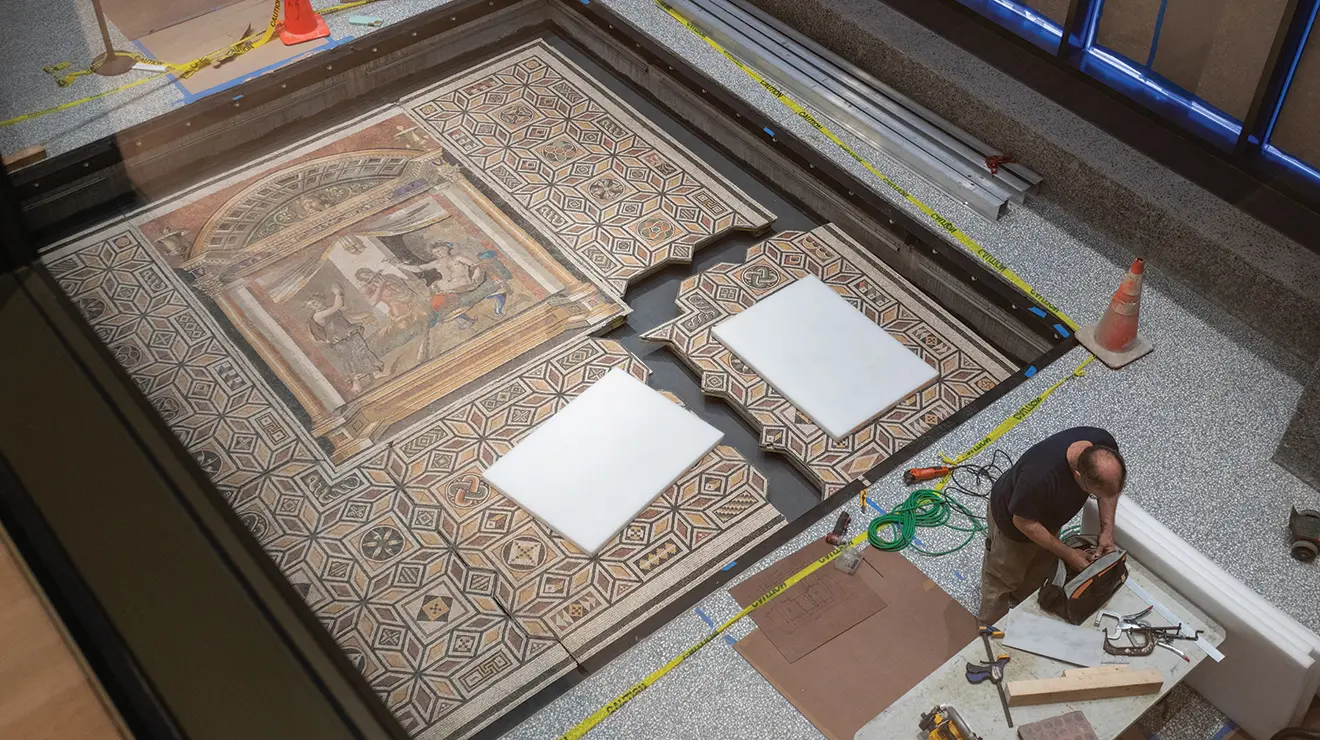

The Spanish staircase with sections dating back to 1549 that was displayed in the old museum was cleaned, and staff “repositioned some of the elements” after reviewing archival research and photographs that provided additional insight. Visitors may also recognize three mosaics that previously were installed in the ground, though viewers could not stand on them. Now, thanks to protective glass flooring and specially made cavities, that’s no longer the case, bringing together the concepts of “preservation and close looking,” according to Chris Newth, senior associate director for collections and exhibitions.

Steward tells PAW that materials of the building itself should also be reminiscent of the previous museum, including timber in the floors, ceiling, and roofing system that are a nod to the teak featured in the old building. The exposed beams, which act as load bearers, were also selected for timber’s relatively low carbon footprint.

Another of Steward’s goals was to replicate tucked away spots and corners. “In the old museum, there was a space that we used to refer to as the atrium where we anecdotally have the evidence that any number of couples got engaged. And so, I … said to the architects, give us spaces where you can imagine that happening.”

Steward wouldn’t say how much this all cost, though at Wintersession, he gave a hint: “Museum construction is among the most expensive forms of construction in the world, not least because of climate and security systems. Museum construction often goes somewhere between a thousand and two thousand [per] square foot. I’ll let you ponder.” He also said the cost of the roughly 35 cases that display art reached eight figures on its own.

“If any of you are asked how many people does it take to construct a case, it is a lot,” joked Newth at the same event.

The reopening of the museum will coincide with PUAM’s publication of a book about its history and mission, with essays contributed by Steward and others. Steward is also working on his own book about what he believes a museum should be that he hopes to complete after a long-overdue sabbatical.

But Steward and the rest of PUAM’s staff are now entirely focused on the months ahead, with daunting tasks still yet to be completed before visitors first step inside.

“Just to get to the point where it’s becoming very real again is much more exciting than it is nerve-wracking,” says Steward.

Though many likely won’t know the story of how the new museum came to be, Ochs Dweck believes “the most exciting stories will be those that visitors come to on their own, as they encounter objects and find their own meanings.”

Julie Bonette is PAW’s writer/assistant editor.

No responses yet