In New Book, Lanny Jones ’66 Decries Excessive Celebrity Culture

Jones, a former People magazine and PAW editor, criticizes America’s adoration of the rich and famous in ‘Celebrity Nation’

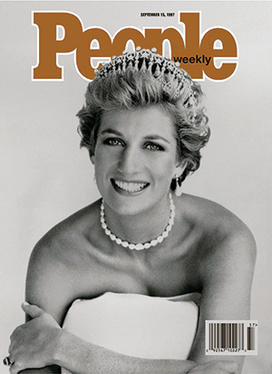

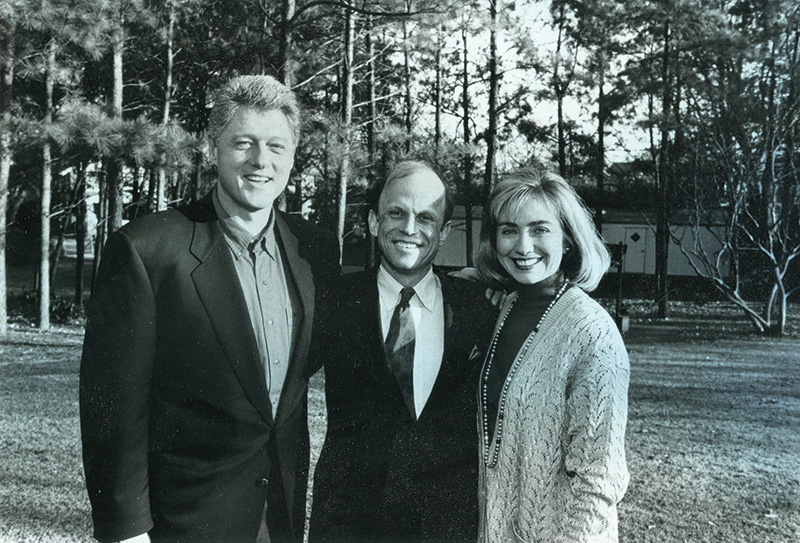

Jones, who joined People magazine at its launch in 1974 and edited it from 1989 to 1997, had a front seat to the rise of celebrity culture. (He also edited PAW from 1969 to 1974). Under his leadership, People became the highest-selling print magazine in the country, much of it on the backs of celebrities. Heart-rending stories about the famous sold a lot of copies, and the cardinal rule of celebrity journalism, he learned, was “Write about a woman with a problem.” No one embodied that maxim better than Princess Diana; the most successful People features, Jones notes, stuck to a simple formula: “Di, diet, and dying.” The magazine’s cover story following her death in 1997 sold more than 3 million copies, making it the second highest-selling People cover ever.

Jones identifies fellow St. Louisans Stan Musial and Chuck Berry as his personal heroes. He also tells stories about his own encounters with the famous. As a sophomore trying out for The Daily Princetonian in 1963, Jones was asked to interview Malcolm X, who was speaking on campus. “He’s not going to want to be interviewed by some preppy privileged kid,” Jones recalls thinking, “but when I met him, he was charming and thoughtful, the opposite of what I had expected. I thought, you mean I could get paid to do this?”

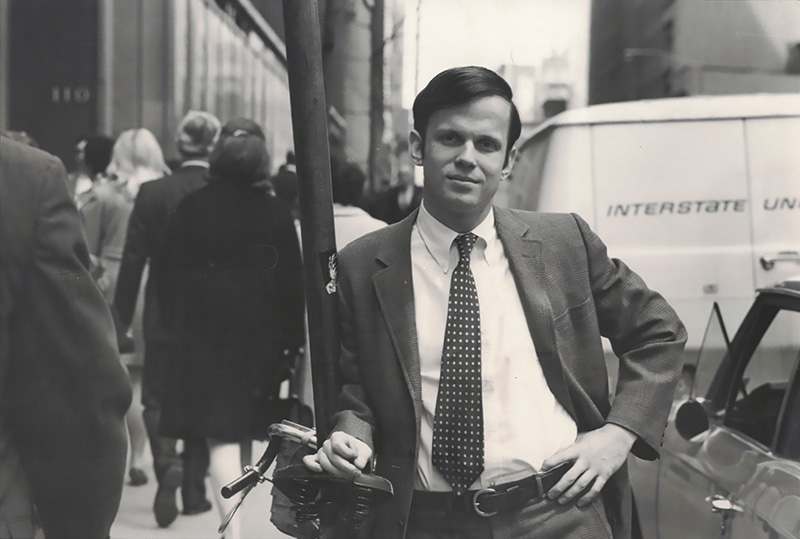

That he did. As a junior staffer for Time magazine in the late ’60s, Jones was assigned to interview actor Jon Voight, who was in New York filming Midnight Cowboy. Voight had little to say, but his co-star, a young actor named Dustin Hoffman, was happy to chat. “There’s always a little reality check that goes on with celebrities,” Jones realized. “You never know until you meet them.” Among the celebrities he got to know at People, Jones singles out Diana and Elizabeth Taylor, both of whom used their fame to draw attention to larger causes.

Having seen celebrities up close, it is no wonder that Jones is not starstruck. “I’ve always been curious about people, and that helps me,” he says. “I have no hesitancy about walking up and introducing myself to anyone.” The best way to break the ice with someone famous, he has found, is to ask about their parents. “Once you ask that question, their defenses sort of drop away.”

Taking a five-year break from People, Jones edited Money magazine, which won three consecutive National Magazine Awards. A former visiting professor at Princeton’s McGraw Center for Teaching and Learning, he is the author of three other books, two about Lewis and Clark. In his 1980 book, Great Expectations: America and the Baby Boom Generation, Jones popularized the term “baby boomer” to describe the generation born after World War II.

Although he decries the rise of celebrity culture, Jones and People contributed to making a lot of it. “Some of the book is a mea culpa,” he acknowledges. Occasionally, he tried to break out of the mold and use the magazine’s huge platform to address pressing social issues, such as racism in the entertainment industry. In 1996, two decades before #HollywoodSoWhite, Jones assigned and edited a People cover story titled “Hollywood Blackout” about the dearth of Black producers and directors, as well as how few Black actors were nominated for major awards.

That issue, he notes sadly, “bombed at the newsstands.”

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to correct the date of People magazine’s “Hollywood Blackout” cover story.

No responses yet