A New Dimension

3-D printing increasingly popular as a research tool for student projects

Editor's note: Following is a revised version of the story published in the April 22, 2015, issue:

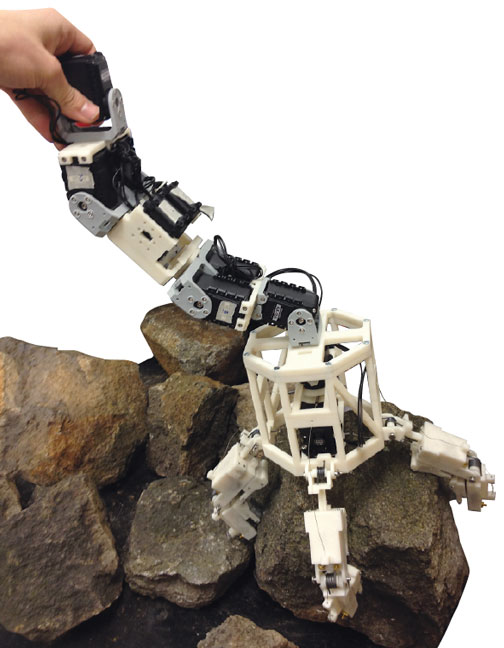

For their thesis project last year, three seniors designed and tested a model of a robot with high-tech grippers that could land on and explore an asteroid.

“Basically, it works the same way that beetles climb walls — there are these tiny microspines on their legs, and they reach up and drag across the surface to find these little nooks and crannies on the surface,” said David Newill-Smith ’14, who created the robot along with Albert Boohene ’14 and Timothy Trieu ’14.

It’s not unusual for mechanical and aerospace engineering majors to build a space vehicle or robot. But the seniors’ project had a twist — they used a 3-D printer to construct their working model.

Over the last several years, it has become more common for students to incorporate 3-D printing into their research. In 2013, one student used 3-D printed parts to create a model of a spacecraft that could land on Mars.

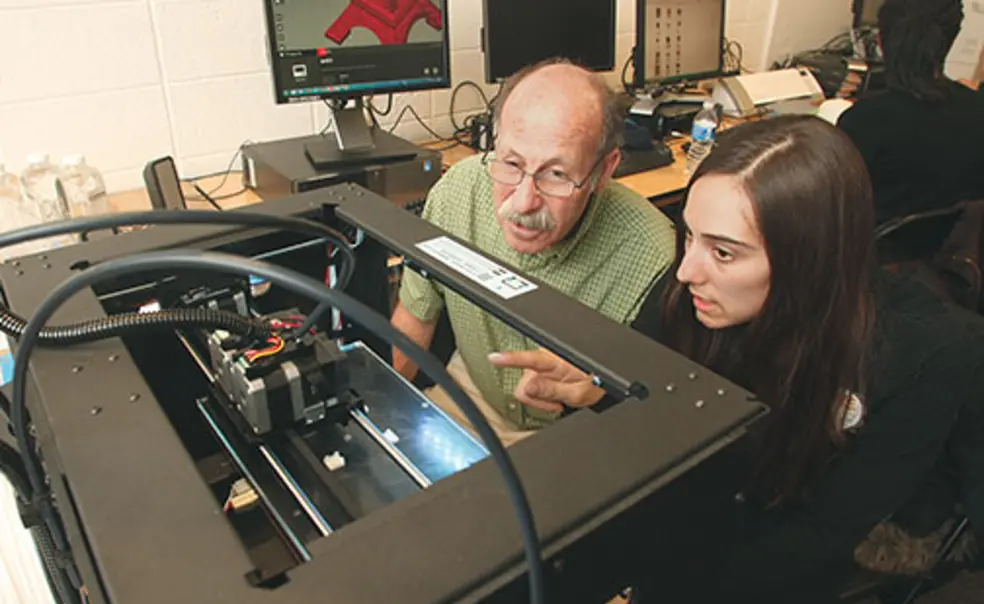

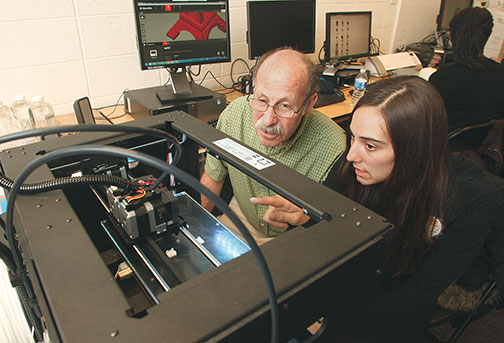

When Professor Michael Littman secured funding in 2006 to purchase a 3-D printer, MAE became the first department at Princeton to utilize the technology in its undergraduate courses. Since then, every MAE major has taken a course in engineering design, learning how to use computer-aided design programs that serve as a platform to create and print 3-D objects.

The first step in 3-D printing is to create a computer-generated design of the desired object; the printing software then slices the model into thousands of horizontal layers. This file is uploaded to the 3-D printer, which has a nozzle that dispenses a thin layer of plastic or other materials. The object is produced layer by layer until the process is complete.

Littman said 3-D printing allows computer-aided designs to be easily constructed and tested. Engineers previously required custom-ordered metal parts to test out their designs, a process that was generally more expensive and took much longer.

“We get to this intermediate stage of testing out ideas much more quickly because you can draw it faster than you can build it,” he said.

Because most of the 3-D printers on campus are available only to faculty members and students in certain departments, a group of undergraduates formed a 3-D printing club last year that any student can join.

Since September, membership has jumped from about 40 students to nearly 300, said club president Mark Scerbo ’18. Items printed by students have included a model of the brain, a playable flute, and a replica of the Princeton shield, he said.

“The main appeal of 3-D printing for me, and I think most students, is the freedom to truly create whatever you can think of,” said club member Sunny He ’18.

Princeton faculty members also are using 3-D printing as a research tool. One MAE assistant professor, Michael McAlpine, who drew national attention two years ago for his work on a “bionic ear,” recently headed a project in which researchers 3-D printed tiny light-emitting diodes into a standard contact lens, which allows the device to project beams of colored light. The research was lauded as the first step toward the creation of high-tech contact lenses that can beam data and moving images onto the user’s eyeballs. The project was funded by the Air Force, which hopes to use the contact lenses to monitor pilots’ health and alertness.

As it turned out for Newill-Smith, his thesis adviser wasn’t the only one impressed with the asteroid gripper. After sending NASA a copy of his thesis, he landed an interview at the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California and was hired as a robotics mechanical engineer. “It’s a dream come true,” he said.

For the record: Michael Littman is undergraduate departmental representative of the mechanical and aerospace engineering department. His position was reported incorrectly in the original version of this story.

No responses yet