New ‘Oppenheimer’ Film Projects a Brilliant Physicist’s Life

When he arrived in Princeton after World War II, J. Robert Oppenheimer was second only to Albert Einstein as the most prominent scientist in the country. The “father of the atomic bomb,” the brilliant physicist had led the Manhattan Project at Los Alamos National Laboratory, resulting in the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki to end the war. His new appointment leading the Institute for Advanced Study (IAS), an independent research center, should have been the capstone to his distinguished career. By 1954, however, Oppenheimer would be publicly disgraced, wrongly pilloried by the House Un-American Activities Committee and by Sen. Joe McCarthy as a traitor to his country.

“Oppenheimer in 1945 was hailed as a national hero by Democrats and Republicans alike, put on the cover of Time and Life,” says Kai Bird, co-author of the book American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer, the source for Oppenheimer, a new movie released this month by Universal Pictures starring Cillian Murphy (Oppenheimer), Emily Blunt (Kitty), Matt Damon (Leslie Groves), and Robert Downey Jr. (Lewis Strauss). “And then just nine years later, he’s humiliated in this secret kangaroo court proceeding and he becomes a nonentity, suspected by his critics of being disloyal at best and at worst, maybe a spy.”

Bird’s co-author Martin Sherwin, who died in 2021, started the book in 1980, assembling 50,000 pages of documents from archives, before calling in Bird to help. The book was published in 2005 and won the Pulitzer Prize the following year. While Oppenheimer may be known for his development of the bomb, Bird says it was his Princeton years that dedicated both authors to the story. “The Manhattan Project was interesting history, but it didn’t have a personal narrative arc to it,” Bird says. “What really made it fascinating was this tragedy that followed.”

Following the war, Oppenheimer — known to students and colleagues as Oppie — resigned his position at Los Alamos. “He was finished building weapons of mass destruction and didn’t want to have anything more to do with that,” Bird says. When Lewis Strauss, the IAS board president, recruited him, Oppenheimer jumped at the post, which came with a hefty salary and accommodation at Olden Manor, an 18th-century farmhouse with ample grounds. Founded in 1930, the institute was conceived as a quiet retreat for top scientists free from the burdens of teaching. “It was the ultimate ivory tower,” Bird says. Oppie himself called it an “intellectual hotel.” While the IAS is separate from Princeton University, the two institutions have always had a close relationship — for example, Oppenheimer gave public lectures at Princeton.

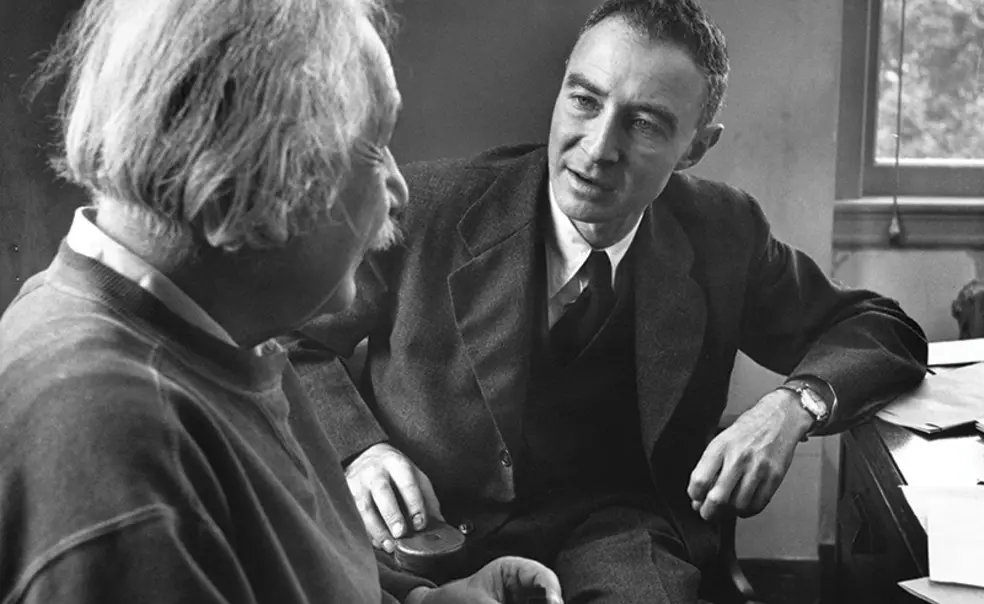

Every afternoon, fellows gathered to mingle and exchange ideas over high tea. The institute’s most famous occupant, Einstein, had been in residence since 1932, and now Oppenheimer essentially became his boss. He also recruited promising young scientists as fellows, and persuaded Niels Bohr, Paul Dirac, and other leading quantum physicists to come for sabbaticals. Oppenheimer supported and encouraged the mathematician John von Neumann in the construction of the world’s first high-speed computer in the basement of Fuld Hall. “It was an amazing, groundbreaking achievement,” says Bird about the computer, which is now at the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C.

Oppenheimer also worked to make the IAS more interdisciplinary. Educated at a progressive school on the Upper West Side, he had a lifelong love of poetry and studied Sanskrit at Berkeley to read the Bhagavad Gita. “What made him a role model as a scientist is that he was a polymath,” says Bird. “Yes, he lived in this rarefied quantum physics world, but he was also a humanist.” He recruited other humanists, such as historian Arnold Toynbee, social philosopher Isaiah Berlin, and historian and diplomat George Kennan 1925, who wrote his great books on the history of Russia on Oppenheimer’s watch. He even brought the poet T.S. Eliot to Princeton for a semester.

While Oppenheimer was no doubt happy during his early years in Princeton, Bird says, his marriage became strained by his wife Kitty’s descent into alcoholism and erratic behavior. Then again, Oppenheimer could be erratic too. “He was the kind of intellectual who could be very sweet and patient with students, but he could be highhanded and rude to people who presumed to be in position of authority.” Increasingly, that meant Strauss, a man with a healthy ego, felt professionally and personally snubbed by Oppenheimer. Their personalities were set up to clash — while Strauss was a conservative, devoutly Jewish, anti-communist cold warrior, Oppenheimer was a secular Jew who made no secret of his leftist sympathies and former association with the Communist Party in the 1930s. “They were like oil and water,” Bird says.

When Strauss became head of the Atomic Energy Commission, advocating for a newer, more powerful hydrogen bomb, Oppenheimer publicly came out against the weapon in the pages of Foreign Affairs. After revelations that another scientist was a spy at Los Alamos, Strauss began to suspect Oppenheimer of treason, referring him to the House Un-American Activities Committee. “He orchestrated this letter of indictment, set up this security hearing, and picked the three panelists in what became a witch hunt against Oppie,” Bird says. In 1954, the hearing was leaked to The New York Times. Eventually Oppenheimer was stripped of his security clearance and access to government, effectively becoming a pariah.

Despite his public disgrace, the IAS never abandoned Oppenheimer, who remained director until 1965. The following year, Princeton University gave him an honorary degree at Commencement, hailing him as a “physicist and sailor, philosopher and horseman, linguist and cook, lover of fine wine and better poetry.”

When Oppenheimer died in 1967, 600 people came to his memorial service at the University’s Alexander Hall, including Nobel laureates, politicians, scientists, and poets. “In this small town of Princeton, we have been proud to have him as a leading citizen,” said then-physics professor emeritus Henry D. Smyth 1918 *1921 during his remarks at the service, which were also published in that year’s March 14 edition of PAW. “Princeton University has continued to enjoy close and happy relations with the Institute for Advanced Study. Our scientists rejoiced in their opportunity to know Robert Oppenheimer as a physicist and as a man.”

Bird is thrilled with the film — some of which was shot on Princeton’s campus and at the Institute for Advanced Study — praising it as true to the book and Oppie’s life. “I hope it will start a national conversation about history and nuclear weapons and the Atomic Age and McCarthyism,” he says. “He was literally the chief celebrity victim of the whole McCarthy era.”

5 Responses

Liz Hallock ’02

2 Years AgoWhen Will Our Culture Stop Lionizing Womanizers in Film?

Christopher Nolan presents J. Robert Oppenheimer as a womanizer in his latest larger-than-life biopic. He equates sex with death, in one scene, reading from sacred Hindu text the same words he spoke at the Trinity testing. (An artistic choice that has Hindu audiences outraged.) Nolan knows that audiences easily excuse misogyny by accepting the fact that “that was acceptable male behavior then.” But Nolan makes choices that further marginalize the women in the plot. Oppenheimer was a professor at Cal when he started dating a 22-year-old post-baccalaureate student. Despite her largely untreated major depressive disorder, Oppenheimer continued the relationship at times during his marriage. In real life, her family believed she killed herself, but Nolan frames a pair of black gloves in the scene where she drowns. The notion that it was the FBI, and not a serious disease, depression, and the strict gender and sex roles of the time that killed Jean Tatlock minimizes this woman's genuine struggle. Nolan also gives limited space to the fascinating character of Kitty Oppenheimer, played by Emily Blunt, one of the most talented female actors of our day. Kitty was a scientist herself and was so tired of New Mexico that she left her second child with a physicist to take respite with her parents for a few months (the second child, a girl, ultimately committed suicide in the 1970s). The audience is already aware that women of that era were marginalized. But here there were at least two incredible characters Nolan failed to further develop, who broke barriers by studying in the sciences, but are memorialized in the film as accessories of a “great” man and take of misogyny.

David Garbern ’74

6 Months AgoRecommending BBC’s Oppenheimer Series

The 1980 BBC series, also called Oppenheimer, was a far, far superior retelling of both the technical and the human drama of the Manhattan Project and of Oppenheimer’s later life. Still available for viewing online and via DVD. Worth the investment of seven hours even if you’ve seen Nolan’s movie already.

btomlins

2 Years AgoOppenheimer’s Honorary Degree

Your fine story on the film Oppenheimer in PAW’s July/August issue mentions the honorary degree J. Robert Oppenheimer received from Princeton in 1966. For those of us present for that Commencement, it was an unforgettable moment. The other honorary degree recipients — all male, all white — stood up and down, and the audience applauded politely. Then when Oppenheimer received his degree, the entire audience unexpectedly rose to its feet in a spontaneous ovation that went on and on. The gaunt and frail Oppenheimer turned and faced the audience silently.

It was a scene that brought tears to many eyes.

He died less than a year later at 62.

David Abromowitz ’78

2 Years AgoRemembering Martin Sherwin

In writing about the new Oppenheimer film (Research, July/August issue), the reporter mentions that the Pulitzer Prize-winning biography on which the movie is based was co-authored by Professor Martin Sherwin (left). Marty deserves far more than a passing nod. He taught and researched at Princeton from 1973 to 1980, and during that time I had the joy of having him as both my policy conference leader and my thesis adviser.

Marty was a gifted teacher as well as an exceptional researcher and talented writer, having already produced A World Destroyed (1975), the award-winning definitive history of the development and decision to drop the A-bomb. In typical modest fashion, when Marty and co-author Kai Bird won the Pulitzer for the Oppenheimer biography American Prometheus, he told The Tufts Daily, “I think the Pulitzer Prize and a dollar twenty-five gets me on the metro.” I am sure I am not the only Princetonian who will take special pleasure while watching the movie in remembering Marty’s long impact on our lives.

George Chang ’63

2 Years AgoMemories of Oppenheimer and the Institute

I plan to watch Oppenheimer when it is released. The PAW article brings back memories ...

For example, how my classmate Dean Ishiki and I rode our bicycles to the Institute for Advanced Study in our first winter at Princeton. Dean was from Hawaii, and I was from New Mexico. We were two of the three Asian-Americans in the Class of 1963. Neither of us had the money or time to go home for the holidays. So we explored the area around the University. We took some photos at the institute. I might still have those pictures.

In my senior year, I had one of the only dates of my college years. We rode bikes to the institute.

In my undergrad years, I attended at least one seminar given by George Kennan. But I was so tired that I fell asleep, and I cannot remember much of anything about the event.

I do remember a man reviewing a manuscript of a Kennan book. I was riding a train to Baltimore, and I noticed a man who was intently reading a thick pile of galley proofs. “Are you a professor?” I asked him. He answered that he was not, but then he asked why I had asked that question. “You look very scholarly,” I replied. He then laughed and said, “Many people look scholarly.”

Within minutes I learned that he had just published the best-selling Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. He was William Shirer.

I also remember some events with Robert Oppenheimer. I was paid to set up chairs and usher at one of them. Oppenheimer spoke in a whisper to the anxious people crowded around him. I couldn’t elbow my way through the crowd. So I didn’t hear much from the Great Man. I don’t remember the words, but I remember the atmosphere of the session.