New Podcast Reveals Joint History of Music and Computers at Princeton

‘Composers & Computers’ weaves storylines about science, art, and friendships

Composers & Computers, a new podcast series from Princeton’s School of Engineering and Applied Science, started with a fun fact. In the early days of the E-Quad’s Computer Center, when time on the University’s IBM mainframe was dominated by faculty with sponsored research projects, some of the machine’s most frequent users outside of that core group came from an unexpected place: the music department.

Aaron Nathans, digital media editor for the engineering school, learned that in a conversation with Ken Steiglitz, the Eugene Higgins Professor of Computer Science, emeritus.

“I used to be a newspaper reporter, and I know a great story when I hear one,” Nathans says. “And it was a better story than I could have expected.”

Through interviews and research, Nathans discovered interwoven storylines about science, art, friendships, and the extensive interdisciplinary links between the computational and musical realms at Princeton. His reporting eventually led him to produce the five-part Composers & Computers series, which launched earlier this month.

The series begins with the work of Milton Babbitt *42 *92, a noted theorist who composed 12-tone music for an analog synthesizer in the 1950s, and traces a path to the present, telling the stories of a current generation of computer-generated music pioneers. Along the way, the episodes delve into some of the early technical challenges in the field (synthesizing speech, for example) and showcase the work of several notable Princeton faculty and alumni, including James K. Randall *58, who created some of the earliest surviving recordings from the Princeton Computer Center using software from Bell Labs, and the prolific composer Paul Lansky *73, the William Shubael Conant Professor, emeritus.

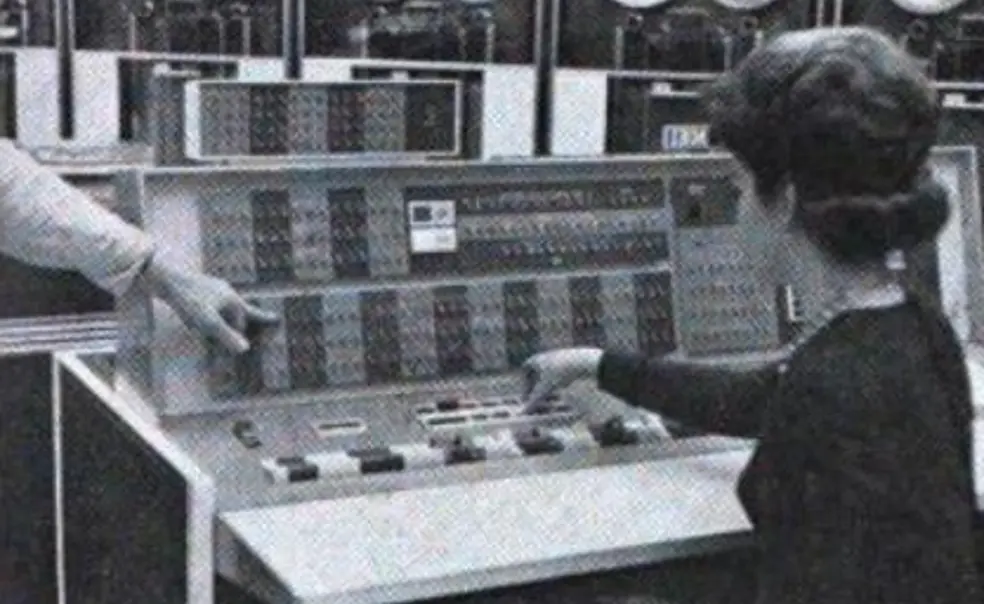

To bridge technology and music, creative individuals from seemingly disparate departments worked through problems together. The third episode, “The Converter,” highlights one of these fruitful collaborations, between Steiglitz (electrical engineering) and Godfrey Winham ’56 *64 (music), who developed a close friendship while tackling the challenge of converting digital tape into analog audio.Why was Princeton at the leading edge of computer music? Geography played a role, Nathans says: In addition to being 40 miles down the road from Bell Labs, the University was linked to nearby researchers at RCA. But Nathans also credits the atmosphere on campus, where composers and computer engineers had “freedom to … go down unexplored paths and see where they lead — and nobody over your shoulder telling you not to do that.”

While many of the innovative composers at Princeton eventually returned to acoustic instruments, they maintain pride in helping the wider computer-music ecosystem grow. “A lot of them feel like there really is no such thing as computer music anymore,” Nathans says, “that it’s just music and that a computer is just another tool to make music.”

1 Response

Linda Seltzer *91

2 Years AgoAn Inclusive History of Computer Music

I was a graduate student in music and had four years of financial aid, two years towards the master’s and two years towards the doctorate. During my first two years of graduate study at Princeton, 1989-90 and 1990-91, I composed “Autumn Cove, Spring Night,” a computer music composition with signal processing algorithms applied to Chinese poetry and Chinese musical instruments. This composition was accepted as a paper and as a concert piece at the International Computer Music Conference in Hong Kong in 1993 and Japan in 1996. It was also performed in the Netherlands and Massachusetts.

I came to the program with a master’s degree in electrical engineering from California Institute of Technology and all of the music major courses for credit as a non-degree student at the University of California, Berkeley. I was bullied by other students in this program and went in another music direction at Princeton, and that shouldn’t have happened. However, I had a career in speech and audio signal processing in private industry, primarily AT&T Labs, and taught part time at four community colleges in New Jersey. My years of hard work and achievement and dedication should not be erased by being left out of this history. In addition, an undergraduate student who is Black spent many hours in the studio producing R&B music, and the history of his work in electronic music at Princeton is also excluded. I wrote to the author about these issues and the problem wasn’t resolved. I am presenting this history here and still hope that the authors here will foster an environment of inclusion and include my work and that of the Black student.