Not your mother’s Princeton

Alumnae mothers and daughters recall what has changed – and what remains the same

Half a century ago, Princeton admitted its first female degree candidate: graduate student Sabra Follett Meservey *64 *66, in the Department of Oriental Studies; not until 1969 would women enroll as undergraduates. This month — April 28–May 1 — the campus hosts its first celebration of its undergraduate and graduate alumnae, with a conference headlined: She Roars.

The history of women at Princeton predates Meservey: Back in 1887, Evelyn College was founded as a “sister” school to Princeton. Its students — who called themselves “The Orange and White” — lived next to the Princeton College campus, maintained a demanding academic schedule, and had full access to Princeton’s libraries. The college was short-lived, however, and closed in 1897 because of debt and falling enrollment.

Princeton remained all-male for the next 60-plus years — but then, change came swiftly. Five undergraduate women enrolled as critical-language students — not matriculated Princeton students, but crucial for their role in beginning to transform campus culture — in 1963. The next year, biochemist Tsai-ying Cheng became the first woman to earn a Princeton Ph.D. And in September 1969, after a 24–8 vote by the trustees on coeducation, Princeton enrolled 101 freshman women, 49 female transfer students, and 21 women formerly enrolled in the critical-language program.

To mark She Roars, New York Times economics reporter Catherine Rampell ’07 spoke with three mother-daughter Tiger couples — and her own mother, Ellen Kahn Rampell ’75 — about their different Princeton experiences.

Clockwise, from top left: Ellen Kahn Rampell ’75 and Catherine Rampell ’07; Elizabeth Hay Haas ’76 and Laura Haas Davidson ’06; Linda Brantley Bell Blackburn ’71 and Akira Bell Johnson ’95; Arlene Pedovitch ’80 and Rebecca Kaufman ’11 (Photos: Courtesy Catherine Rampell ’07; courtesy Elizabeth Hay Haas ’76; courtesy Akira Bell Johnson ’95; Frank Wojciechowski)

Ellen Kahn Rampell ’75 and Catherine Rampell ’07

My mom was a babe. I mean, she still is a babe, but back when she was at Princeton in the mid-1970s, when women in general were members of a rare breed, she was a babe.

I know of her years of überbabedom primarily from photos and from her classmates, who still giggle when they recount the tales of the many men who pursued her. My mother generally blushes and changes the subject when I ask about her college social life. But when PAW asked me to write an article about mother-daughter Princeton legacies, I knew this was my best chance to finally do some long-delayed, dating-related dishing.

My mother finally would comply, because she’d do just about anything in the name of Princeton. Especially if that anything involves remembering her own days on campus, which were pretty much uniformly, deliriously blissful.

“Apparently the first 40 days of my freshman year, it rained every day,” she says. “I didn’t notice it until someone pointed it out to me. I was just so happy to be there.”

Foul weather wasn’t the only thing she was a little bit oblivious about.

In talking with my mother about the differences between her experience and mine, the starkest discrepancies have to do with our classmates’ attitudes toward class. Not coursework — caste.

In my time at Princeton, I remember a student body that seemed hyperaware of socioeconomic distinctions — and in many cases the need to show off, and pursue, wealth. Some of it had to do with the clubs, but a lot of it had to do with clothes and shopping and career choices. Signifiers like popped shirt collars, a brand logo, or a pair of men’s pastel pants were cues of some form of superior breeding (until many such signals, like the popped collar, were adopted by “the riff raff,” of course).

And while the prep look supposedly was worn “ironically” — often while playing an “ironic” game of croquet supposedly to make fun of Princeton’s WASP-y reputation — such trappings truly felt like they were meant to indicate who was in the know about what WASPs were supposed to look like.

My mother remembers her time at Princeton much differently. There were plenty of rich kids and children from famous families with Roman numerals appended to their surnames, sure. She even dated some of them. But she really didn’t know who was rich and who wasn’t.

Some of that may have to do with her upbringing. She was from a middle-class family in Teaneck, N.J., and her father was a restaurant-supply salesman. If people wore alligator insignias, she wouldn’t necessarily have recognized them as a sign of the manor-born. On the other hand, my own childhood was much more privileged. I went to fancier schools with wealthier classmates than my mother had. I had been exposed to — and, as a somewhat self-loathing prep was probably more sensitive to — such signs of conspicuous consumption.

But my liberal-guilt baggage aside, there were very different attitudes on campus toward wealth and class in my time there than in my mother’s. Almost 60 percent of my 2007 classmates who left campus with full-time jobs went into finance and consulting. In the 1970s, many components of these services didn’t exist, and likely wouldn’t have had much recruiting success on campus if they did.

When my mother traipsed around Old Nassau, the Vietnam War was raging, students were protesting the draft, and the world was in social upheaval. Going to business school or working in finance was uncool; students wanted to change the world.

“People were very anti-establishment when I was there,” my mother said. “And so if anything, people downplayed that they came from wealth, because the wealthy were part of the establishment.”

And it showed in the way people dressed, too. People wore ratty jeans — or as my mother calls them, “dungarees.” Girls didn’t get manicures or wear makeup or go shopping at expensive Nassau Street boutiques on the weekends, as seemed to be common when I was on campus.

Surely there were other things people did to impress their friends, but identifying with WASP culture wasn’t one of them.

My mother, a retired accountant who lives in Palm Beach, Fla., says she probably was one of the few girls at the time who wore skirts and dresses regularly. That’s not because she was trying to make any political statement, she says, but because that’s what her parents had bought her in high school.

But whatever her reasons, I’m pretty sure it didn’t hurt her babeness to be showing those gams.

She went on a lot of dates, with a lot of men (something my father, Richard Rampell ’74, was not too thrilled about at the time. But things of course turned out OK for him later on). She was especially popular with the Jewish guys, since with her blond hair and blue eyes she says she was “a Jew who looked like a shiksa, the best of both worlds.”

Not all of the male attention she received was desirable, flattering though it must have been. Despite her many polite refusals, for example, she had a preceptor who kept asking her out — sometimes in front of the other students — making for some awkward class discussions.

I was more of a serial monogamist in college, something my mother used to chide me for. Play the field, she would urge me.

“I don’t see why you restrict yourself to just one boy,” she told me once. “When I was in college, I dated hundreds of boys. And so by the time I got married, I knew what I wanted.”

Again, I’d like to think this is a generational thing.

Elizabeth Hay Haas ’76 and Laura Haas Davidson ’06

Speaking of campus romance: Among the many common reasons why Betsy Hay Haas ’76 and her daughter, Laura Haas Davidson ’06, are devoted to Princeton is that Princeton played matchmaker for both.

Betsy applied to Princeton because she was “a nonconformist,” and the idea of being one of the first women to attend what had been an all-male school appealed to her. When her friends and family warned her that attending a school dominated by men could be a “hassle,” she shrugged them off, saying she wanted the challenge.

But to some extent they were right. Even though she arrived on campus three years into coeducation, it didn’t always feel that the local male species was accustomed to the estrogen injection.

“You couldn’t walk from here to there without people watching you,” she says. “Not in a super-creepy stalking way. Just that you could see people thinking, ‘Oh, what is that? A student? Oh, and it’s female? Isn’t that interesting.’”

It was a phenomenon that she would experience again when she went to law school a few years later — also at an overwhelmingly male campus — and that she says gave her “excellent training” for her years as an attorney. (She now works as a photographer in Houston.)

Aside from being scrutinized on the path to class and occasionally asked for the “female perspective” in precept, early female Princetonians also had to deal with another source of awkwardness: rules regarding communal bathrooms.In her freshman year, Betsy was in what is now known as Forbes, then known as Princeton Inn, in the annex. She was in a double, the only female freshman representation on the floor. On the hallway were also three all-male doubles, one of which housed Betsy’s future husband, Stanley Haas ’76, known as Buddy.

Also on that hallway were one women’s bathroom and one men’s bathroom.

About a month into the school year, the boys sent a delegation to the girls’ double: Could the two genders consider sharing each other’s commodes?

Betsy and her roommate thought it over, and said they would allow just two of the men to utilize the officially female facilities — but the women got to choose which two men had access. Buddy was not among the chosen two. “He was the one I was least interested in,” says Betsy.

Until the evening of the first snowfall, that is. That night, the residents of Princeton Inn rushed out to the golf course behind their dorm to frolic in the fresh snow.

“We went out there while it was snowing, while there was snow on the grass, and it was just a magic moment that happened: Laura’s dad and I shared our first kiss,” Betsy says. “And we’ve been together since then, to this day.”

Laura’s was also a winter romance.

Jamie Davidson ’06 lived in sixth entryway of Holder, and Laura, now a high school English teacher in California, lived in the fifth. They had “parallel friend groups,” she says, and the first time she noticed Jamie was in the dining hall. In her English-major’s words: “Light streamed in from the tall windows in Rocky, and suddenly there were these bright blue eyes that just lit up. I insist I set my sights on him first.”

Thus began the first of many -ships: a friendship that became a long courtship that finally culminated in a romantic relationship, in the winter of their sophomore year.

Betsy happened to be on campus for an alumni meeting the very weekend her daughter’s romance began. Laura’s roommate, Amy Widdowson ’06, pulled Betsy aside and told her, “Betsy, we’ve all seen this coming for a long time. This is really happening now, and we’re all so excited, and I just had to let you know.”

The mother had a premonition that only a few years later, Laura and Jamie would be back on campus saying their I-do’s.

After all, Betsy says, “It snowed that weekend."

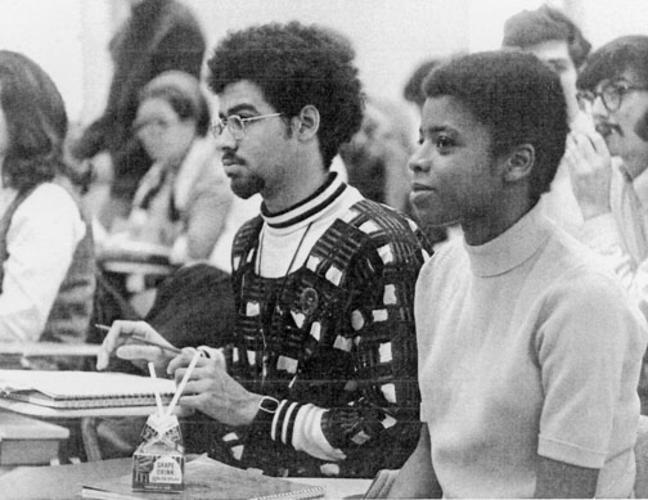

Linda Brantley Bell Blackburn ’71 and Akira Bell Johnson ’95

The distinction of being Princeton’s first mother-daughter pair is shared by Linda Blackburn ’71 and Akira Bell Johnson ’95.

Linda — Linda Brantley in her student days — spent the first two years of her higher education at Douglass College, which was then Rutgers University’s all-women’s school. Her introduction to Princeton was as an “import,” the somewhat derogatory term for women who were bused in from girls’ schools to attend social events on Prospect Avenue. At these events she made some friends, and eventually she attended a few lectures with her newfound Tiger companions.

When Princeton went coed, she jumped at the chance to apply. And so she entered the first graduating class of Princeton women.

“We were put on campus and put under a microscope to see what happened,” she says. “They wanted to see if indeed women and men could study alongside each other in the very same classroom.”

At the time, many coeducation skeptics doubted that was possible: “They said if girls were there, the men couldn’t talk honestly. And the women wouldn’t be able to pay attention because they’d be so distracted by the men,” Linda remembers. “There would be no honest discourse.”

Women were an oddity on campus, not fully integrated into the social life of the campus or of the town. Linda says she spent more time at the eating clubs as a Douglass import than she ever did once she was a full-time Princeton student. She does not recall a single store on Nassau Street that sold clothing for women. The female students lived near each other, without much support.

In two ways, Linda found herself as a sort of odd-woman out. One was that she is female, of course. The other was that she is black. As few women as there were, there were probably fewer black students, she says. It was a time of great political and social change for minorities of all kinds, but for these two groups on campus in particular.

While women at Princeton were fighting for a voice, Linda spent more time and energy thinking about the role of the black community on campus. Her parents had taken her to political rallies in Washington, D.C., when she was a child — she participated in marches led by Martin Luther King Jr. — and her interest in civil rights grew.

She recalls that most black students she knew were first-generation college attendees. She had grown up in an integrated community (in Roselle, N.J.), but many had not. And not all of the white students were welcoming. She remembers that some white students poured a keg of beer on a black classmate — clad in his only suit — just as he exited Brown Hall. A fight broke out, and security officers had to intervene.

Years after Linda left campus, when her daughter, Akira, would become the first to fulfill a mother-daughter Princeton legacy, Akira still wouldn’t find much female or black company. The campus had become much more diverse, but her major — engineering — hadn’t.

Like her mother, Akira often was the only woman, and the only African-American, in her classes. And like her mother, she occasionally heard disparaging remarks about her academic potential based purely on her gender and race.

But also like her mother, Akira thrived, even if the rigor and competition of the engineering school were a shock to a woman who had been at the top of her high school class with her “eyes closed.”

“My academic career took a little time to be stellar,” says Akira. “It was a big shift to go from being a straight-A student in high school to struggling for a B-. I think my parents were a little taken aback when that first report card came home.”

She assured them she’d get things in order, and she did, pulling long hours studying and sleeping only about four to six hours each night during the week.

Akira, now a program director at the Hess Corp., says her 9-year-old twins, Samantha and Ethan, have “a while yet to go” before they start making “their own decisions” about college.

But it is already a Princeton family, and Samantha has the potential to become the school’s first all-female three-generation Princetonian.

“That would be kind of a fantasy,” Linda admits.

Arlene Pedovitch ’80 and Rebecca Kaufman ’11

Stuyvesant High School in Manhattan, alma mater of Arlene Pedovitch ’80, used to send a boatload of students to Princeton every year. Of Arlene’s senior class, a whopping 24 students were admitted to Old Nassau, she recalls.

Newly admitted Arlene, however, never had visited. So in April, before making her final matriculation decision, she hopped on the train from New York to take her first Orange Key tour.

The campus was gorgeous that spring day. The guide walked the admitted students and tourists through Nassau Hall and Prospect House’s gardens, pointing out the Revolutionary War hotspots and recounting famous alumni who’d walked those very paths.

And then they got to the Chapel.

“Don’t laugh, but I’d never been in a church before,” Arlene says, noting that she came from a traditional Jewish family. “We get there, and I’m thinking to myself, ‘Gee, this place really kind of looks like a church.’”

She was, to put it mildly, put off. She interpreted the stop at a Christian place of worship as a subtle clue about what the University expected of its student body.

“I thought that probably meant it wasn’t really the right place for me, and I left the tour group,” she says.

She began a leisurely walk back to the train station to head back to New York. On the way, she ran into some friends who had graduated from Stuyvesant the year before. She told them she was crossing Princeton off her list. Aghast, they insisted that she stay for lunch, and then for a night with the gang. They showed her a good time, and she changed her mind.

“I’d been pretty close to turning around and saying this is not for me,” Arlene says. “But then spending time with them, suddenly it seemed something more comfortable.”

Arlene, now a banker in Princeton who has served on alumni committees and as a class officer, says she has told that story to Dean of Admission Janet Rapelye and President Tilghman, because she thinks it holds lessons for today’s recruiting efforts. “We need to think about what it is we want to say about ourselves as a university and a prospective community to applicants who don’t have the same background as we do,” she says.Once she enrolled, Arlene went through the usual growing pains of adjusting to life away from home, but soon fell in with a group of friends with whom she is still close today. Some were Jewish and some were from New York, but many had backgrounds quite different from hers.

The main social division she says she felt on campus had to do not with gender or religion, but — as I would find again a few decades later — with class.

At the time, the eating clubs were not all coed — she was a classmate of Sally Frank, who successfully challenged the admission policies of three men-only clubs in court — but in any case, Arlene says she did not see herself belonging to an eating club. A scholarship student, she saw the clubs as places that appealed to wealthier students.

So she took her meals at Stevenson Hall, which was then the main alternative dining option for upperclassmen, and also worked there on occasion to help support herself.

“Certainly, even if financially it were no issue, I still would not have felt comfortable in an eating club. None of my close friends ate in eating clubs, either,” she says. “Maybe one sign of progress is that now my daughter is in Tower. So was my roommate’s daughter, in fact. We couldn’t believe it.”

By the time Arlene’s daughter, Rebecca Kaufman ’11, applied to Princeton, the campus’s multicultural offerings, and sensitivities, had blossomed. The Center for Jewish Life, for example, opened in 1993. Even as a Tower Club member, Rebecca takes many of her meals at the CJL, and she was president of the center’s board for a year.

If Princeton felt scary and unfamiliar to Arlene, it had the potential to be almost too familiar for Rebecca.

Like many children of Princeton alumni, Rebecca had spent a lot of time on campus as a child at Reunions and basketball games and class meetings, with people always clad in those garish orange and black get-ups. An upbringing set to perma-Princeton has a way of turning off adolescents from Tigerdom.

Plus, her mother lived about 10 minutes away.

“There were definitely a lot of factors pushing me to not go, including the fact that I was a teenager,” Rebecca says. Many other eventual legacies have expressed similar initial reluctance. “Then there was the proximity and just wanting to do something different and be in a different place.”

But then she visited again as a potential student, on her own Orange Key tour, and fell in love.

Catherine Rampell ’07 is an economics reporter for The New York TImes.

Leah J. Haynesworth ’11 is a PAW intern.

SHE ROARS: APRIL 28–MAY 1Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor ’76 will take part in a discussion with President Tilghman Friday evening, April 29, as part of the conference She Roars, which features faculty lectures, panel discussions, and alumnae presentations on topics ranging from the student experience today to undergraduate campus leadership, parenting, and women in business and finance.

Environmental Protection Agency director Lisa P. Jackson *86 will speak at the Friday luncheon; best-selling novelist Jodi Picoult ’87 will address participants on Saturday; and Teach for America founder Wendy Kopp ’89 will speak at dinner Saturday. For a schedule, go to http://alumni.princeton.edu/ main/news/calendar/sheroars.

3 Responses

Lenore Patow

2 Years AgoFirst Five Women to Study at Princeton

I find it odd that no mention is ever made of the first five female students to enter Princeton University in 1963 (Critical Languages Program). It’s almost as if we never existed.

We didn’t graduate from Princeton but were admitted as juniors. I was admitted as a junior but CCNY gave me the extra 10 units I needed to graduate so that I could continue my studies as a graduate student at Stanford University.

It’s all water under the bridge now but I just thought I’d write to you since when I googled my name and Princeton 1963 I found no mention of any of the five girls who were really the pioneers of breaking the gender barrier at one of the most prestigious universities of that time.

Editor’s note: Read more about the Critical Languages Program in PAW’s May 15, 2019, issue.

Phebe Miller ’71

10 Years AgoThe first undergraduate women

PAW’s article, “Not your mother’s Princeton,” erroneously states that Linda Brantley Bell Blackburn ’71 “entered the first graduating class of Princeton women.” That distinction did not belong to our class, but to the Class of 1970, since some of the women who had been critical-language students in 1968–69 stayed at Princeton for their senior year and graduated in 1970 as Princeton students on the basis of having spent two of their undergraduate years at Princeton.

Editor’s note: According to Christie S. Peterson, project archivist with the University Archives, the nine women who are members of the Class of 1970 (Judith Ann Christine Corrente, Susan Mary Craig, Sue Jean Lee, Lynn Tsugie Nagasuco, Melanie Ann Pytlowany, Agneta Riber, Mae W. Wong, Mary Peggy Yee, and Priscilla Read) attended Princeton prior to their senior year as part of the critical-language program. They matriculated as Princeton students as seniors.

Shannon Stoney ’76

10 Years AgoMother-daughter Tigers

I was excited to see Catherine Rampell ’07’s article about mothers and daughters who both went to Princeton (feature, April 6). I was in one of the first classes that included women undergraduates, the Class of 1976. While I don’t have a daughter, I was interested to see how Princeton — and women — have changed since I was at Princeton.

Sadly, it seems that despite all our progress over the last 40 years or so, women still are obsessed with clothes and boys! The first two profiles were about what women wore, then and now, and whom they dated, and how they found their husbands! I’m sure that these women did other things besides get dressed and go out on dates.

Luckily, Linda Brantley Bell Blackburn ’71 and her daughter Akira ’95 did talk about academics in their profile, and Arlene Pedovitch ’80 and Rebecca Kaufman ’11 also mentioned other aspects of campus life besides clothes and dating.

I hope this article doesn’t send a message to prospective women students that female students at Princeton mainly are worried about how they look and whom they are going to marry. You can think about those things anywhere. The reason you should think about going to Princeton is that you will get a first-class education there.