Critical Languages, Critical Steps

How an artifact of the Cold War brought change to Princeton

It is remembered best for yielding the first nine undergraduate alumnae, but the Critical Languages Program of the 1960s changed Princeton University in other ways, too, in that turbulent decade.

It was an egalitarian experiment born of two necessities: closing gaps in the ranks of analysts and scholars who spoke the languages of America’s two biggest adversaries, the Soviet Union and Communist China, and of strategic allies in the volatile Middle East and Far East; and Princeton’s need to fill largely vacant classrooms in study of those regions.

The women — called “Critters,” half affectionately, half derisively — were an afterthought, a byproduct of the fact that the mostly coed liberal-arts colleges to which Princeton reached out told Nassau Hall in no uncertain terms that they would not send male students if females could not apply on an equal footing. From The New York Herald Tribune headline on April 11, 1963, that shouted, “Girls at Princeton — After 217 Years,” to the phalanx of reporters and photographers elbowing one another to chronicle their arrival, the young women garnered the lion’s share of attention, so much so that some were unaware there were male language students, too. The Daily Princetonian, in a 2014 retrospective, unearthed a memo in the University Archives at Mudd Library in which an administrator groused about the ingratitude of female students who looked “sullen” and “scornful” during Life magazine’s shoot.

Today those nine women who graduated in the Class of 1970 draw cheers at the P-rade as the pathbreakers for coeducation, but what of the rest, male and female? Was the experiment in teaching 19- and 20-year-olds advanced levels of difficult languages — instruction normally offered only in graduate schools — a success? Did it yield, as one booster in Nassau Hall predicted with confidence, top contributors to their fields?

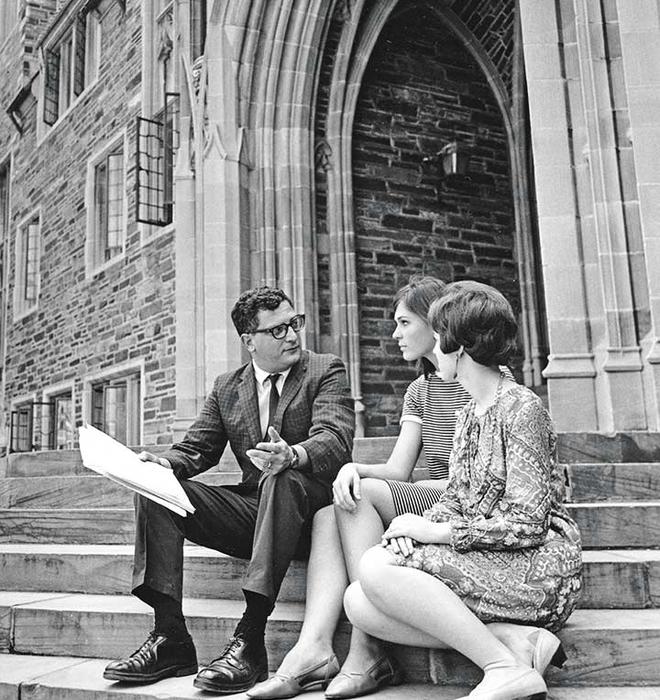

It did produce “some very, very serious specialists and scholars,” says Allen Kassof, a former Princeton sociology professor and then-assistant dean of the College who was the program’s director from 1965 to 1968. Kassof, 88, who left Princeton in 1968 to build a scholarly exchange organization with the Soviet bloc, says, “Even as little as a 10 percent yield of people going on would have been a significant success, and I suspect it was more than that.”

Many followed different paths, to the law, medicine, teaching, journalism, and even entomology and air-traffic control. They speak warmly of life inside Princeton classrooms and, for many women, ruefully about life outside them.

While it certainly served a national need, the program also satisfied faculty hunger for more students for their classes in Asian, Middle Eastern, and Eastern European studies. “We are at present very well armed but have very few students,” Dean of the Faculty Merrill Knapp lamented in a memo. In October 1962, faculty members in those areas were given a green light to let colleagues across the country know that top students who had exhausted the offerings at their home campuses would be welcomed as students to Princeton.

Within months a broader solution emerged. With $125,000 from the Carnegie Corporation of New York — equivalent to $1 million today — Princeton formed a partnership with 32 mostly smaller liberal-arts colleges to send language students to Princeton as visitors. The University pledged to spend $50,000 to $100,000 on its own.

The colleges and Princeton hammered out details over the winter. Initially Princeton refused to commit to accept females, citing housing and other obstacles. Even after that was worked out and the program was unveiled in April 1963, it was not until mid-June that the Board of Trustees gave its assent to “the admission on an experimental basis of a few highly qualified and carefully selected women as special students ... and not as candidates for Princeton degrees.” President Robert Goheen ’40 *48, in a 1989 Prince article, denied that the Critical Languages Program was a back-door attempt to undermine Princeton’s “monasticism.” He said the women “were heroic to brave our all-male campus.”

Nine men and five women started classes in September 1963, the young men in dorms and the young women sent to live in a hall at the Princeton Theological Seminary before being moved to a bare-boned Victorian house with a chaperone and finally to the Graduate College. “They were afraid that somehow it would be dangerous for us to be closer to campus,” says Susan Chizeck *75, a University of Texas, Dallas, lecturer who had studied at Douglass College in New Jersey and who took Japanese classes at Princeton from 1967 to 1969. She later returned for a master’s degree in sociology and earned a master’s in East Asian studies at Stanford and a doctorate in social work from Rutgers.

“The social atmosphere was somewhat strange, but the experience was extremely valuable for me,” says Chizeck.

Alexander Berzin also spent two years (1963–1965) at Princeton learning Chinese. The Rutgers chemistry major was stymied in persistent efforts to transfer, although he got special permission to store his senior thesis in Firestone. Tibetan Buddhism became Berzin’s passion and life, and he worked for the Dalai Lama in India after earning a Harvard Ph.D.; he’s now in Berlin overseeing his studybuddhism.com website. “I had an extremely wonderful, enjoyable, and stimulating time at Princeton,” Berzin says.

The Herald Tribune’s April 1963 article alerted Barbara Alpern Engel, a Russian-studies major at the City College of New York, to the opportunity. “My memories are almost entirely positive,” says the retired University of Colorado Russian-history professor, despite the “unsubtle reference” in the 1964 Bric-a-Brac to the fact that four of the five women were Jewish. “The Princeton chapter of Hadassah sent out a welcome wagon,” a yearbook essayist wrote.

Another of the original students, William Atwell *75, from Washington and Lee, later returned to Princeton for a Ph.D. in East Asian studies and chaired the Department of Asian Languages at Hobart and William Smith Colleges. Several Princeton undergraduate classmates also became professors in the field. “Being in the same class with those people was a real joy,” says Atwell, who also remembers playing in a student jazz combo at Wilson Hall “at a memorable cocktail party given by Ambassador George Kennan [’25],” famous as author of the containment theory on preventing the spread of communism.

Susan Harrigan *77 (1964–1965) was a history major at Connecticut College for Women who’d spent two summers studying Russian in high school. “It was a very rich experience,” says the retired journalist, who freelanced in Vietnam and wrote for Newsday, The Wall Street Journal, and other newspapers. She remembers Professor James Billington ’50, a cultural historian of Russia, saying, “Don’t write me the Old Testament. Just write one perfect page in a blue book.” Harrigan, who played a nurse in a Theatre Intime production of Mr. Roberts, later spent a year at Princeton on a Sloan Fellowship for economic journalists.

The late Sue-Jean Lee Suettinger ’70 made an even bigger splash on the stage at Princeton, starring in A Different Kick in 1968–69 as the Triangle Club’s first woman. Her future husband, Robert Suettinger, had been a critical-languages student a year earlier. They met at Middlebury College’s summer school, after his Princeton year and before that of Lee, who was born in Canton (now Guangzhou), China.

Robert Suettinger, a retired Central Intelligence Agency China specialist from Lawrence University who did stints on the National Security Council and at the State Department, says learning Mandarin “has been the dominant factor in my life. I was a small-town kid from Wisconsin. Going to Princeton was something I never expected to do. I like to think, given where I ended up and the kinds of things I’ve done, they got their money’s worth out of it.”

University of Oxford anthropology professor emerita Martha Mundy, a Swarthmore College classics major, took Arabic classes at Princeton in 1966–1967 and has spent a lifetime researching the people and societies of the Arab world, spending years in Yemen and Lebanon. “Princeton was an eye-opener to this New Yorker,” says Mundy, who was appalled by weekend “cattle runs,” when boys brought in busloads of girls for mixers. “In all my life I haven’t seen such overt class expression of the objectivization of women en masse.”

A number of critical-languages students were the children of immigrants whose first language at home was not English, but the language of their parents or grandparents. The grandfather of Tamara Turkevich Skvir, a Douglass College student who spent 1964–1965 at Princeton, was the head of the Russian Orthodox Church in North America. Her father, John, was both a chemistry professor and the Orthodox chaplain at Princeton, and mother Ludmilla was the first woman to teach at Princeton in 1944 and later a professor at Douglass.

Since she was a faculty brat, all-male Princeton “didn’t faze me,” she says, although she recalls that in her first class, “none of the boys would sit next to me.” But in another class, Daniel J. Skvir ’66, son of an Orthodox priest, recognized her and asked her to sit beside him. They married in 1967, he was ordained and is Princeton’s Orthodox chaplain, and both also taught school.

Skvir and Nelle Williams Brown (1966–1967) both were struck by the same phenomenon in precepts: They felt that boys who hadn’t done the readings managed to dominate discussions, talking off the tops of their heads. Brown, a polyglot economics major from Smith College, was shocked by their “arrogant flaming ... but took away confidence in having my own voice and standing my ground in predominantly male environments.” The MIT Ph.D. became a political scientist who worked on international development and health issues for NGOs, Congress, and the World Health Organization.

Mary Yee ’70, daughter of immigrants from China’s Guangdong Province, went from Girls’ High School in Boston to Bryn Mawr College. She eventually became a labor and community organizer in Philadelphia, as well as a school administrator and, with an education doctorate, a researcher at the University of Pennsylvania.

Princeton then was “too conservative, elitist, and male” for her liking, “but I learned a lot and became politically conscious because of the Cambodian strike and all the teach-ins.” She enjoyed the East Asian studies department but winces at remembering the professor in an architecture elective who invited the class to see his Bauhaus home and said, “Mary Yee can lead you all with a dust cloth.”

Mae Wong Miller ’70 was majoring in biochemistry at Queens College in New York when a professor encouraged her to apply to the languages program. She already had studied Mandarin in a summer class at Columbia for gifted high schoolers. At the Graduate College she met her future spouse, physicist Matthew Miller *74, and later became a business consultant and human-relations executive as well as the first female member of the Princeton Club of New York, where she prodded the board to open up its stag Tiger Grill — as it soon did.

“I owe a lot to Princeton. It prepared me for something I never would have expected, to enter a business world so male-dominated,” she says. “I had a head start. It changed the trajectory of my life.”

Others’ language skills soon atrophied, but they remain indebted to Princeton.

“I’m delighted I did it,” says James Garofallou, a psychoanalyst who majored in philosophy at Hamilton College. He thought his facility in Mandarin might lead to government service, but his interest in psychology won out. “Learning Chinese is an ongoing, forever enterprise. To memorize the characters, [and] you can forget them very quickly ... I was most appreciative of the opportunity, even if I didn’t use it in the way perhaps intended.”

Raffaello Orlando *81 (1967–1968) taught classical Chinese and Chinese philosophy and religion at universities in Venice and Naples, finished his Ph.D. in East Asian studies at Princeton, and then devoted most of his career to classical music. A clarinetist who majored in music at Haverford College, he grew up in London and New York, where his father was a correspondent for Italian radio and television. He and wife, Ghit Moy Lee, a pianist, have played recitals around the world and sent daughter Sofia Orlando ’14 to Princeton. His career “wasn’t quite what the Critical Languages Program had in mind, I guess,” says Orlando, but East Asian studies “was just wonderful.”

Among the most accomplished academics with the Critical Languages Program on their résumés — most participants still list it — is University of California, San Diego, China scholar Susan Shirk, who says the 1965–1966 year was essential to her career. “I suppose I could have started Chinese after graduating from Mount Holyoke, but it really gave me the push to go on to get my Ph.D. [from MIT]. Otherwise I might have gotten married and put my husband through graduate school, which is what most women did those days.”

When Shirk, in 1971, was in the first group of scholars admitted to China after the advent of pingpong diplomacy, Princeton issued a press release proudly noting that she was “making history.” But looking back, Shirk says, “I never felt that Princeton treated us like we were somehow Princetonians. After we left, it never stayed in touch. I thought that was a little odd, especially for a school famous for cultivating alumni.”

That grievance is felt even more acutely by Pauline Reich, an expert on cybercrime and former law professor at Japan’s Waseda University who is now at the Rajaratran School of International Studies in Singapore. She has tried without success to be recognized as an alum.

Reich, a City College of New York student who studied Persian at Princeton in 1966–1967, says, “Princeton did not welcome us into all of the benefits of alumni status, such as career networking or access to membership in the Princeton Club(s)” in New York and elsewhere. Reich, who also worked for the federal Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights for 16 years, believes it is not too late to redress what she deems a wrong. “It’s time,” she says.

There was doubt whether the program would last beyond the Carnegie grants — the initial period of three years was extended to four — but the Ford Foundation stepped in with $161,000 in 1967. The program lasted until 1972, training upwards of 200 students over its run. Though an enthusiastic federal grants manager had dangled the prospect that Washington would kick in funds, that never happened, with the exception of loans for summer language classes. Princeton was unwilling or unable to keep it going alone.

All along there were worries in Nassau Hall about its viability. By 1967 the University was casting about to forge a national consortium and enlist Stanford and other major schools to do what Princeton was doing by itself.

“There exists a national need which the relatively small Princeton program alone cannot satisfy,” a program report said. With an eye toward philanthropies, it calculated that for less than $2 million, such a consortium could train 400 more students in five years and provide “a permanent and realistic solution” to the dearth of critical-languages talent.

It was not to be.

In 1979 a presidential commission issued a report decrying Americans’ “scandalous incompetence” in foreign languages. (Kassof served on that commission.) Later, in 2006, the U.S. State Department began awarding hundreds of full-ride summer scholarships to send undergraduates abroad to learn 15 critical languages, including Princeton’s original six, Korean, and others such as Urdu, Hindi, and Swahili.

And without importing visitors, Princeton today has hundreds of students in intermediate and advanced critical-language classes, primarily Mandarin, but also Arabic, Japanese, Korean, Russian, and Farsi as well as Urdu, Hindi, Swahili, and Turkish.

It’s a proud and now long tradition. Beyond its contribution toward coeducation, the Critical Languages Program also showed the University living up to the motto Princeton in the nation’s service.

Plus ça change ...

Christopher Connell ’71 is an independent Washington writer and editor.

7 Responses

John G. McCarthy Jr. h’67

6 Years AgoHonorary Solution

Susan Shirk and Pauline Reich regret that Princeton forgot about them after they completed their Critical Languages year (feature, May 15). The solution could be to make them — and other CL students who wish — honorary members of their classes.

I came down from Williams to study Arabic in the Critical Languages Program in ’65–’66 and was delighted to be elected an honorary member of the great Class of ’67 a few years later. Since then, I pay class and Ivy Club dues, read PAW cover to cover, and attend Reunions. I am more attached to Princeton than to Williams.

As for Arabic, my business career focused on the Mideast, and I have just published the first volume of my Arabic short stories titled (translated) Hanna’s Diaries — Coming of Age in the Land of the Cedars, available at Jamalon.com. Shukran (thank you), Princeton!

Robert F. Ober ’58, Foreign Service (retired)

6 Years AgoLanguage Scholars

I enjoyed the report on the 1960s program but wish it had noted the labors of that sweet-tempered, dignified gentleman Piotr Eristov who, bound for a career in the Tsarist calvary when the Revolution broke out, eluded the Bolsheviks and made his way to Princeton. There he guided eight or 10 of us through basic Russian.

The report did mention Ludmilla Turkevich, who helped me on my senior thesis, faulting me correctly for reading some of the relevant Stalin-era novels in English translation. Still, I managed to acquire enough Russian to enjoy three assignments in Moscow as well as TDY assignments to Kabul and Prague to deal with potential Soviet defectors. Sadly, I never thanked my mentor personally, but years later, Piotr’s nephew, Class of 1944 and a deputy mayor under John Lindsay, provided the details of his escape at a luncheon he hosted.

Nicholas Clifford ’52

6 Years AgoLanguage Scholars

I enjoyed very much your article on the “Critters” of the 1960s and ’70s. Having graduated from Princeton in 1952, done a tour of service with the Navy and earned a Ph.D. from the institution on the Charles River, I found myself back in Princeton for a few years as an instructor in the history department. Then, thanks to a career change (from European to Chinese history) in 1967, I did an introductory summer Chinese course at Yale (only a year later would the largely Princeton-built summer Chinese School at Middlebury open). At Yale, one of my classmates was a Vassar junior, Vivienne Bland, on her way to Princeton as a Critter that fall.

At Princeton she also baby-sat occasionally for our daughters so my wife and I could go out. One evening she was let in by our 7-year-old Sarah, who asked her what she did. “I’m a student,” replied Vivienne. Sarah’s eyes grew side with astonishment. “I thought only boys could be students,” she said, her remark overheard unfortunately by my Radcliffe-educated wife, who was perpetually concerned about our raising our children in such a socially backward atmosphere as Ol’ Nassau.

Recently our former baby-sitter and Princeton’s former Critter, now Vivienne Bland Shue, has retired from her position as Leverhulme Professor of Chinese Studies at Oxford and one the leading scholars of Chinese political science of our day.

“Princeton in the Nation’s Service,” your article concludes. Yes, but sometimes Princeton has to be dragged, kicking and screaming, in that direction.

David H. Shore *76

6 Years AgoLanguage Scholars

Thanks to PAW for the excellent article on the Critical Languages Program (feature, May 15). The program was life-changing for me as I elevated my career aspirations to earning a Ph.D. in East Asian Studies at Princeton and then to serving at the National Security Agency, where, at the outset, I made good use of my language skills. I fully agree with my CIA colleague Bob Suettinger that the program’s return on investment for Princeton and our nation was quite high. Moreover, the Chinese-language training I received was exceptional, including the training at the Middlebury College Chinese Summer Language Program. That program was directed by Princeton’s Chinese-language faculty and was already world-class although only in its third year when I attended in 1968.

However, I do note with sadness that others who attended the Critical Languages Program but who did not receive degrees from Princeton are not treated as alumni. After all, as I read regularly in PAW, Princeton appears to consider as alumni undergraduate and graduate students who leave the University without receiving a degree. Surely something can be done to right this wrong, even at this late date. Then my 1968–69 roommates (Ted Davis, Jim Garafallou, Bob Gordon, and Mike Weiskopf) could read this letter.

Brooks Wrampelmeier ’56

6 Years AgoLanguage Scholars

The article about women critical-language students at Princeton reminded me of an earlier instance of a female foreign-language student at the University before it went coeducational.

Katherine W. Bracken was a mid-career Foreign Service officer (FSO) who studied Turkish at Princeton in the mid-1950s. I recall seeing her at a social event that I attended at the Graduate School in early 1956.

As a new FSO in the fall of 1956, I was assigned as a staff aide to the dean of languages at the Foreign Service Institute (FSI). Going through some office files, I discovered correspondence between FSI and T. Cuyler Young, chairman of the Department of Oriental Languages and Literature (OLL), regarding the proposed assignment of Ms. Bracken to study Turkish at Princeton. Professor Young initially explained that Princeton did not accept women students. The FSI dean countered that if she were not accepted, the Department of State might not send any FSOs to study there.

Eventually, the OLL department agreed to accept Ms. Bracken as a student of Turkish. However, she would not be provided with University housing or other campus facilities and would not be granted an academic degree.

Ms. Bracken later served as U.S. consul general in Istanbul.

David N. Young ’62

6 Years AgoRussian Studies Before Critical Languages

Just a reminder that Russian at Princeton existed well before the Critical Languages Program. As a 1962 alumnus who majored in Russian language and literature, I can say that there were dedicated students and faculty in the late ’50s and early ’60s who studied and taught Russian. Included were Professor Herman Ermolaev, who died recently, and of course Mrs. Ludmilla Turkevich, who is noted in the PAW article. Unfortunately, we were deprived of the presence of female students who would have added much to our experience. I went on to teach Russian at the U.S. Air Force Academy and Hamilton College, eventually becoming a senior language analyst at the National Security Agency.

Lawrence G. Kelley ’68

6 Years AgoIdentified in the Photo

For those who may be interested, the two young women who are shown speaking with Allen Kassof in the lead photo for the article are Anne Wallace (Kruthoffer) w’68 and Nelle Williams (Brown), both of whom studied Russian at Princeton in 1966–67. As a Russian major, I had many classes with both of them.