Few who knew him in college would have expected great things from Edward Shippen 1845, a lackluster student nearly expelled for disrupting classes after a mere three months at Princeton. Unsurprisingly, Shippen would write later in life that he “never had any great enthusiasm” for his alma mater. He counted no more than three or four “good professors” on the faculty, and dormitory life was squalid. (Apparently Nassau Hall had a bedbug problem in the 1840s.) He regularly arrived late to morning prayers, usually in some state of undress, and certainly didn’t expend much effort studying. Though Shippen managed to graduate with his peers, he did so ranked 48th in a class of 51.

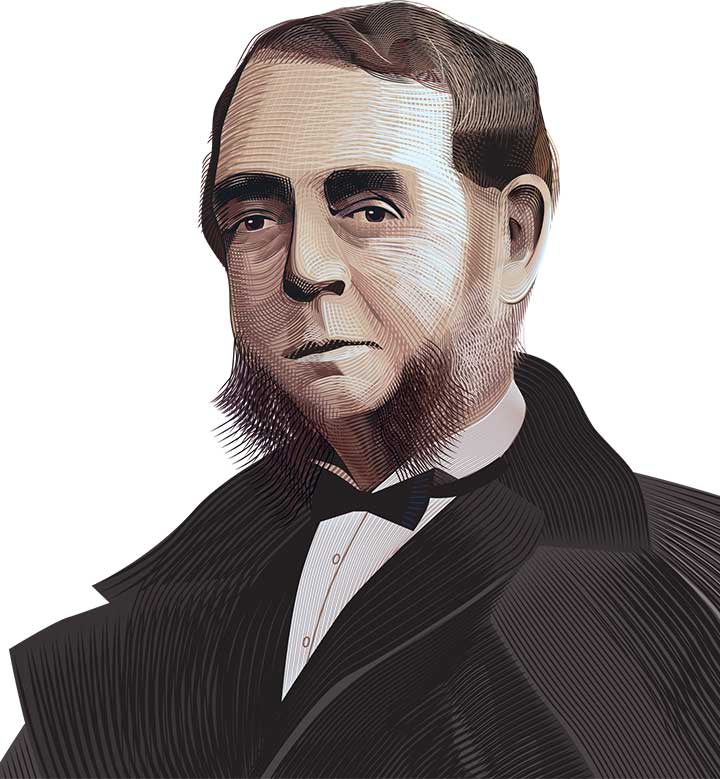

But even Shippen — whose fondest college memories involved hiding jugs of ale in the overgrown grass outside Nassau Hall — matured eventually. With a medical degree from the University of Pennsylvania and the bushy muttonchops of a fashionable mid-19th-century professional, he began a long career as a Navy surgeon. When the Civil War broke out he was stationed on the USS Congress, a Union warship soon to be anchored on the James River in southern Virginia.

The imposing 52-gun Congress deterred blockade-runners seeking to deliver supplies to the Confederacy, but others flocked to it: refugees from slavery steering battered canoes and old fishing skiffs. The fugitive slaves brought military intelligence, like the rumors of a “mysterious vessel” under construction in Norfolk, rising from the hull of the scuttled frigate Merrimack. But “as week after week passed and the monster did not appear,” Shippen wrote, “we were inclined to regard this one as a myth.”

About 112 crewmen were lost in the fight, though Shippen and 29 others managed to struggle ashore before fires raging on the Congress reached the magazine, sparking an explosion that sank the vessel.

They should have listened. On March 8, 1862, the ironclad CSS Virginia — a menacing, metal-plated “leviathan,” to Shippen’s eye — appeared on the river and turned its guns on the Congress. Within moments, as he recalled in gory detail, the warship was “a slaughter-pen, with lopped-off legs and arms, and bleeding, blackened bodies scattered about by the shells, while blood and brains actually dripped from the beams.” About 112 crewmen were lost in the fight, though Shippen and 29 other survivors managed to struggle ashore before fires raging on the Congress reached the magazine, sparking an explosion that sank the vessel. But even then the battle wasn’t over. The Union ironclad Monitor arrived overnight, and the next day Shippen and a crowd of thousands watched breathlessly as it dueled the Virginia.

The sun was “red and angry” when it rose that morning, he would later write, quickly burning off the mist hanging over the river “as if purposely to afford an uninterrupted view of a sight which the world had never seen before.”

It was the first battle of ironclads in history, the gruesome birth of a new era of naval warfare, and Edward Shippen was close enough to touch it. Or at least, it touched him. Shippen had suffered a concussion on board the Congress when a shell struck nearby.

He was one of the luckiest.

1 Response

Michael S. Huckman ’58

7 Years AgoThe Shippen Pedigree

Because of my interest in the role Princeton played in Philadelphia medical history of the 18th century, I wonder if the "ordinary student" referred to in this article is related to a long line of Philadelphia Shippens with strong ties to the College of New Jersey (Princeton) during that era. Judge Edward Shippen of Lancaster was a trustee of the College from 1748 to 1767. His son Joseph Shippen Jr. was a member of the Class of 1753, a soldier, merchant and public figure.

Edward Shippen's brother, William Shippen Sr., was a prominent Philadelphia physician who as a trustee of the College helped architect Robert Smith with the plans for Nassau Hall. His son, William Shippen Jr. Class of 1754, became one of the most noted physicians in Philadelphia, a professor in America's first medical school at the University of Pennsylvania, and director general and chief physician of the armed forces of the American Army during the Revolutionary War. His Brother, John Shippen Class of 1758, studied medicine with his father but had a subsequent life cut short by illness.

If the "ordinary student" was indeed the privileged legacy of the esteemed Shippen family, his ancestors may have been more worthy of a profile in PAW than the student who hid containers of ale in the grass around Nassau Hall.