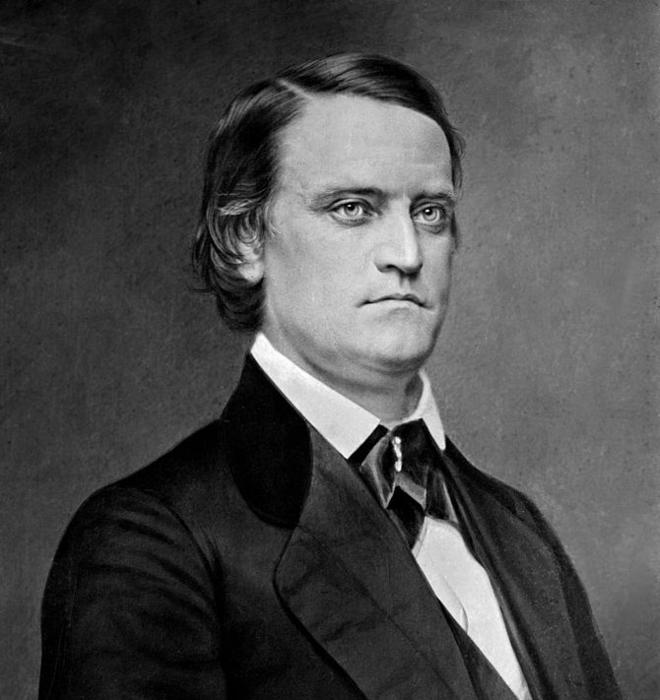

JOHN C. BRECKINRIDGE

Ran for President: 1860

Party: Democrat

Breckinridge, a graduate of Centre College in Kentucky, spent time as a graduate student at Princeton in 1838-39 but did not earn a degree. He became the youngest vice president in the nation’s history when he was elected, at age 35, as James Buchanan’s running mate in 1856. Like Burr, the first vice president from Princeton, Breckinridge would eventually be accused of treason.

Democrats tapped the imposing Kentuckian for their national ticket because he was a rising star with an impeccable pedigree: His grandfather, for whom he was named, served as a U.S. senator and as attorney general in Jefferson’s administration. Through his mother, the younger Breckinridge was related to two past presidents of Princeton: his great-grandfather was John Witherspoon and his grandfather, Samuel Stanhope Smith. His cousin, Mary Todd, would marry Abraham Lincoln.

READ MORE about the alumni who have run for the nation’s highest office in Princeton for President, a feature from our Oct. 26 issue

Over 6 feet tall with deep-set blue eyes and, later in life, a flamboyant mustache whose handlebars grew to almost shoulder length, Breckinridge was, like Burr, frozen out by a jealous president. He won plaudits for presiding impartially over the Senate during a contentious time in the nation’s history. Though a devout states-righter, Breckinridge opposed slavery, supporting an effort to resettle slaves in Africa — an effort his kinsman, former Princeton President Samuel Stanhope Smith, helped to foment.

In the 1860 election, the Democratic party split, with the southern faction supporting Breckinridge for president and the northerners backing Stephen Douglas. Upon Lincoln’s victory, Kentucky’s legislature then named Breckinridge to the Senate, where he worked fruitlessly first to reach sectional compromises and then to keep his state neutral. After his state voted to stay the union, Breckinridge was viewed as disloyal and ordered to be arrested. He fled to Virginia to become a general in the Confederate Army, taking a lead role in major campaigns, including Jubal Early’s daring 1864 raid on Washington, D.C., that made it within sight of the Capitol.

In the last year of the war, Confederate President Jefferson Davis appointed Breckinridge Secretary of War. He worked to bring the conflict to an orderly end. “This has been a magnificent epic,” he told members of the Confederate congress. “In God’s name, let it not terminate in a farce.” He fled to Cuba and then Canada, returning to the United States when President Andrew Johnson issued a Christmas Day 1868 amnesty for Confederate loyalists. Despite pleas from admirers that included President Ulysses S. Grant, he would not again seek elective office. But he spoke out against the Ku Klux Klan as “idiots or villains” and in favor of reconciliation. When Breckinridge died on May 17, 1875, a Minnesota newspaper editor wrote, “Our country mourns from St. Paul to New Orleans and from New York to San Francisco. There is now no North and no South.”

JOHN F. KENNEDY

Ran for president: 1960

Party: Democrat

Kennedy is associated with Harvard perhaps as much as any president, but his first collegiate experience was at Princeton. “Ken,” as his roommates called him, entered in the fall of 1935 as a member of the Class of 1939; an illness cut his time at the University short.

In 2013, on the 50th anniversary of Kennedy’s death, W. Barksdale Maynard ’88 wrote this history column describing how the University mourned the president:

On that unforgettable Friday afternoon, Nov. 22, 1963, grim news spread across campus: President Kennedy had been shot in Texas. University offices closed, classes were suspended, construction equipment fell silent at the half-completed New New Quad. The next day’s Princeton-Dartmouth game and Prospect Street parties were called off. So were performances at McCarter and Theatre Intime, and the movie showings at the Garden and Playhouse theaters.

At the Dulles Library of Diplomatic History at Firestone — a facility dedicated by former President Eisenhower 18 months earlier — a young employee, Charles Greene, was filing cards in a cabinet when he was distracted by secretaries in conversation. Soon one came over and told him about the radio report. Greene, who still works in that same section of the library, told patrons why the reading room was closing early. “They were appalled,” he says, as were so many others.

The Prince published a two-page special edition that included a list of campus mourning services, a statement from President Robert Goheen ’40 *48, and a black-bordered note from the editors calling for Kennedy’s death to “be taken as a rallying cry for the rule of law, of reasoned strength, most important, of unity — for which until Nov. 22, 1963, he stood.” Some students wondered aloud what would become of Kennedy’s civil-rights agenda; Professor Arthur Link, biographer of an earlier Democratic president, Woodrow Wilson 1879, predicted to the Prince that new laws would be passed quickly now.

Many grieved for the dynamic Kennedy, who had spoken on campus several times as U.S. senator. Some shared stories of “Ken’s” brief tenure as a Tiger undergraduate in 1935 (then ill, he remained for less than two months). “It got too tough for me here,” he once joked, “so I transferred to Harvard.” Now Princeton mourned her former son.

No responses yet