Princeton for President!

Two alumni have gone on to the White House — and many others have tried

Over the years, numerous Princetonians have sought the nation’s highest office, and though they are a politically diverse lot, every one was a rebel in a way. One was charged with treason. Others thumbed their noses at the political establishment or inspired constitutional amendments. Here’s a look at nine contenders, from the earliest days of the republic to this year’s primary campaign.

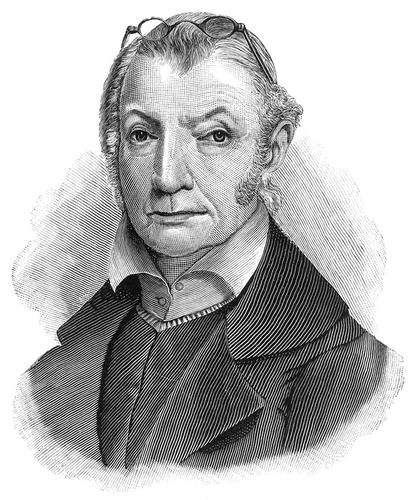

AARON BURR JR. 1772

Ran for president: 1796, 1800

Party: Democratic-Republican

Burr — the brilliant son and grandson of Princeton presidents — first shows up in presidential election records in 1792 when George Washington was running for his second term. One of New York’s U.S. senators and a member of the nascent Democratic-Republican Party (the origin of today’s Democrats), Burr got one Electoral College vote. Four years later, still a senator, he received 30 votes but finished a humiliating fourth.

In 1800, he was informally Thomas Jefferson’s running mate, but the two men tied at 73 votes apiece in the Electoral College.

READ MORE about two other candidates with Princeton ties, John C. Breckinridge and John F. Kennedy

At that time, the presidential election was a free-for-all, with the top vote-getter winning the highest office and the vice presidency going to the runner-up — so the election remained in doubt until, after 36 ballots taken over six days, the House decided in Jefferson’s favor.

The seeds of suspicion, and of Burr’s political destruction, were planted. Jefferson froze out his vice president, refusing to put him on the ticket four years later or to help Burr in the New York governor’s race in 1804. Alexander Hamilton’s opposition also doomed Burr in the gubernatorial contest, leading to the duel that was, in some respects, fatal for both.

JAMES MADISON 1771

Ran for president: 1808, 1812

Party: Democratic-Republican

When Jefferson won the 1800 election, his ally Madison became secretary of state. For a while, the Madisons lived at the White House and Dolley Madison frequently served as the official hostess for the widower Jefferson. Dolley would become an invaluable help to her husband in 1808 when Madison, hoping to succeed Jefferson, faced party rival James Monroe in the caucuses. She hosted dinners for members of Congress, who would have the most to say about picking the party’s nominee. Madison shrewdly brought Monroe back into the fold, winning with 122 Electoral College votes, compared to 47 for Federalist Charles C. Pinckney and six for George Clinton. After becoming the nation’s first wartime president, Madison won re-election in 1812 with just over half the vote — facing Clinton’s nephew DeWitt.

WOODROW WILSON 1879

Ran for president: 1912, 1916

Party: Democrat

Wilson, then the governor of New Jersey, won the Democratic presidential nomination on the 46th ballot after five days of voting. In the general election, the big issue was what to do about the excesses of the great trusts. Roosevelt, gregarious and charismatic, called for a New Nationalism in which a strong federal government would regulate powerful business trusts. Wilson, seen as cold and aloof, responded with a New Freedom platform meant to weaken the trusts and promote competition. “Ours is a program of liberty, and theirs is a program of regulation,” he said in a Labor Day address in 1912.

In the end, Wilson won with 42 percent of the votes, Roosevelt and Taft split Republican voters, and Socialist Eugene Debs got 6 percent, the highest percentage ever won by a Socialist Party candidate. “In its essence, 1912 introduced a conflict between progressive idealism, later incarnated by Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal ... and conservative values,” historian James Chace wrote in his 2004 book about the election, 1912. “For the rest of the century and even into the next, the Republican Party was riven by the struggle between reform and reaction, and between unilateralism in foreign relations and cosmopolitan internationalism.”

NORMAN THOMAS 1905

Ran for president: 1928, 1932, 1936, 1940, 1944, 1948

Party: Socialist

The son of an Ohio preacher, who obtained a divinity degree after graduating from Princeton, Thomas became a spokesman for the underrepresented and underprivileged. Shortly after Thomas’ death in 1968, The Daily Princetonian’s associate editor, Richard Balfour ’71, suggested that Terrace Club rename its building Norman Thomas Hall. “An eating club named after a socialist would add a little verbal panache to the Prospect Street area,” Balfour wrote.

Thomas never got more than 2.2 percent of the vote, a high-water mark he achieved in the 1932 race. For the Class of 1905’s 50th reunion, he puckishly wrote to his classmates: “I’ve failed — doubtless to your general satisfaction! — in the chief purpose of my career. That was to bring about, or help bring about, in our country a more realistic political alignment which might give us two major responsible parties, one of them democratic socialist in principle whatever its name.”

In fact, Thomas felt better about his record, as he confided to a student who walked him back to his hotel after a campus speech. “I asked him what was his biggest success,” that student, Ralph Nader ’55, now recalls in an interview with PAW. “He said, ‘My biggest success was having the Democratic Party inherit my platform.’”

ADLAI STEVENSON II ’22

Ran for president: 1952, 1956

Party: Democrat

He was born with ink and politics in his veins: His family owned a Bloomington, Ill., newspaper, and his grandfather — the first Adlai E. Stevenson — was Grover Cleveland’s vice president.

Stevenson was active in Chicago politics when, as war loomed in the late 1930s, he found his voice on a topic he would own: foreign affairs. His speechifying and other efforts to get the U.S. involved in the fight against Nazism brought him to the attention of the administration. He traveled extensively for Roosevelt, always with a focus on what would happen after the war. “The problems of war,” he said in 1943, “are dwarfed by the problems of peace.”

He ran for Illinois governor in 1948, winning decisively. Seen as a potential presidential candidate, Stevenson became an icon for those battling McCarthyism when, in 1951, he vetoed a bill that would have required loyalty oaths from Illinois public employees and candidates. “Does anyone seriously think that a real traitor will hesitate to sign a loyalty oath?” Stevenson argued.

After dallying about getting into the presidential race, Stevenson made a dramatic entrance in the midst of the 1952 Democratic convention in Chicago and won the nomination on the third ballot. He suffered two landslide losses to the popular Dwight D. Eisenhower. Yet his wit and his willingness to confront fomenters of the Red Scare made him a hero to many Americans during the 1950s.

RALPH NADER ’55

Ran for president: 1992, 1996, 2000, 2004, 2008

Party: Green, Independent

Many Democrats still blame Nader for siphoning enough votes from Democrat Al Gore to throw the election to the Supreme Court, whose ruling propelled Republican George W. Bush to the White House. Nader vehemently rejects responsibility, saying his critics “gave me delusions of grandeur.” But he tells PAW that the 2000 election has taken a personal toll: Once a popular witness on Capitol Hill, Nader now feels shunned both inside and outside of Congress. “All my lectures dried up,” he says. “I couldn’t get advances for my book.” In subsequent presidential runs that Nader describes as “a demonstration project, repeated every four years, to show people the noncompetitive nature of our political system,” the one-time media darling found he couldn’t get traction. “I was closed out by the press,” Nader says.

Nader, who continues to churn out books, has said he won’t vote for Donald Trump or Hillary Clinton this year. He sounds wistful when recalling how Norman Thomas once expressed satisfaction with the influence he had over the Democratic Party. Today, Nader says, the two parties have so “perfected the duopoly that it’s harder for one to have made the impact he made.”

STEVE FORBES ’70

Ran for president: 1996, 2000

Party: Republican

Forbes ran in 1996 because Republican congressman Jack Kemp didn’t: “I was looking around the field to see who shared the similar, positive Reaganesque, Kempesque approach to politics, didn’t find anyone, and so decided, instead of complaining about it, try it yourself.” Forbes likened himself to his grandfather, a Scottish immigrant and business journalist who founded the family’s eponymous magazine: “He didn’t just write about entrepreneurs; he decided to become one himself. So instead of just writing about it, I entered the [presidential] field.”

Though he was not able to rally the populace around his call for a flat tax — the centerpiece of both campaigns — Forbes is philosophical. “You go out there and you try to persuade,” he says. “And you quickly learn, as Lincoln said, events control you as much as you control events. And things are out of your hands, like timing. You’re not master of the universe. So the fact that one didn’t succeed doesn’t mean the process is flawed or the country is flawed. The time was not perhaps right and perhaps you didn’t make a strong-enough case. So don’t blame others.”

He says he pledged to support his party’s nominee this year and faults Trump’s Republican rivals for failing “to lead with real issues” and for failing to articulate their ideas “in a way that meant something to the voter.” When Jeb Bush called for 4 percent economic growth, “I understood what he was saying,” Forbes says. “But you say 4 percent GDP to most people, it sounds like a hair formula. ... He never translated it into something where people could say, ‘Oh, I get it.’

“I sometimes want to do to the political-consulting class what Shakespeare suggested about lawyers,” Forbes continues. “They all stuck to the same playbook, all read the situation the same, and all lost. It’s amazing.”

BILL BRADLEY ’65

Ran for president: 2000

Party: Democrat

Each time, Bradley succeeded — until he ran for president.

Bradley first considered a White House run against President George H.W. Bush in 1992. “I remember my Princeton thesis adviser, Arthur Link, came to me and told me I had a duty to do it,” says Bradley. “I didn’t feel I was ready at that moment. I always felt that if you were going to run for president, you had to really have a feel for the country and experience what it was to be a wheat farmer or a crawfish fisherman or, you know, a prison guard or whatever.”

As President Bill Clinton was wrapping up his second term, Bradley felt his time had come, entering the race for the Democratic nomination against Vice President Al Gore. Despite mounting a successful fundraising campaign and winning supporters ranging from liberal icon Mario Cuomo to basketball titan Michael Jordan, Bradley dropped out after Super Tuesday, having failed to win a single primary.

Today Bradley works for the investment firm Allen & Co. and hosts a weekly radio show. He thinks there’s “way too much money in politics,” that gerrymandering has created a congressional election system that “rewards extremism,” and that the news media have had “a distorting effect on serious discussion of the issues.” Still, he would encourage a young Princetonian to become involved.

“If people of idealism don’t go into politics,” he says, “you abdicate that to people who misuse the system to their own advantage or will be ideologues that will polarize the country or more.”

TED CRUZ ’92

Ran for president: 2016

Party: Republican

Unfortunately for Cruz, the anti-establishment lane in this year’s Republican race would get crowded.

In an apparent attempt to position himself to inherit Donald Trump’s supporters after what professional politicians anticipated would be Trump’s inevitable implosion, Cruz conducted a much-chronicled “bromance” with his rival. But hostilities broke out between the two frenemies as primaries and caucuses winnowed the field, and Cruz appeared to be one of the few obstacles remaining to Trump claiming the nomination. When Cruz took the podium at the GOP convention, he infuriated delegates with his pointed refusal to endorse the nominee.

There’s been some speculation that Cruz was setting the stage for a 2020 White House run with his convention speech, but he’s got another race to win first: His Senate term expires in 2018, and he’s already said that he’s running for re-election.

In an email to PAW, Cruz expressed no regrets over the campaign or its outcome. “Being part of a grassroots movement to defend freedom and our Constitution has been the greatest privilege of my life,” he wrote. He endorsed Donald Trump, affirming his support after release of the tape that prompted other Republicans to withdraw their endorsements of their nominee.

Kathy Kiely ’77 is an editor at BillMoyers.com.

For the Record

The Stevenson family owned a newspaper in Bloomington, Ill., not Bloomington, Ind.

4 Responses

Keating Holland ’82

9 Years AgoMore Presidential Hopefuls

Kathy Kiely ’77’s story about Princetonians who have run for the White House (feature, Oct. 26) was a fascinating look at the impact the University has had on politics. But let’s not be too hasty patting ourselves on the back — for every Princetonian who won the White House or made a major mark on history, there is another alumnus whose presidential candidacy sunk like a stone.

Starting in the 1800s, William Dayton 1825, the GOP’s first vice presidential nominee in 1856, ran for president four years later, but only 14 delegates voted for him. Two Princetonians were dark-horse candidates at the 1868 Democratic convention — former New Jersey Gov. Joel Parker 1839 and Frank Blair 1841, scion of a powerful Missouri political dynasty. Parker’s candidacy never got anywhere; Blair managed to parlay his support into a vice presidential nomination, but he and his running mate, Horatio Seymour, won only six states in the fall.

In the 20th century, George Gray 1859, a former senator serving as a U.S. circuit court judge, attracted some attention at the 1904 Democratic convention as a less-scary alternative to William Randolph Hearst, but the convention ultimately nominated another obscure judge, Alton Parker. In 1928, two Princetonians — former Ohio Sen. Atlee Pomerene 1884 and Huston Thompson 1897, who had chaired the Federal Trade Commission — tried to stop Al Smith from winning the Democratic nomination. Smith beat Pomerene in the Ohio primary that year by more than 40 points, and Thompson finished dead last in the sole ballot that the Dems held at their convention. Ohio Gov. George White 1895 fared a little better at the 1932 Democratic convention, but his 52 delegates were only good enough for fourth place.

In 1936, anti-New Deal businessman Henry Breckinridge 1907 ran a quixotic campaign against Franklin Roosevelt in the primaries and got thumped badly in every contest he entered. Maryland Gov. Daniel Brewster ’46 did win his state’s primary in 1964 by a small margin, but only as a surrogate for Lyndon Johnson (LBJ didn’t want to run the risk of losing to George Wallace, who was also on the ballot). More recently, former Delaware Gov. Pete du Pont ’56 ran for the 1988 GOP nomination, but dropped out after winning only 10 percent in the New Hampshire primary.

Princeton doesn’t fare any better in vice presidential history. Six Princetonians — Blair, Dayton, Richard Rush 1797, John Sergeant 1795, Amos Ellmaker 1805, and Theodore Frelinghuysen 1804 — were on major-party tickets between 1824 and 1868. All lost. No Princeton alum has been a major-party running mate since then.

Norman Ravitch *62

9 Years AgoAll Princetonians should be...

All Princetonians should be ashamed that the only Princetonian who became President was a man whose academic brilliance concealed at times but not for long his Calvinistic arrogance, his inflexibility, his unhealthy delusion of being a Christ, and his advocacy of democracy for all nations which brought disaster to many of them. We almost had a President Burr, of course from Princeton; he might have been no worse than Wilson.

J. Michael Parish ’65

9 Years AgoMore Presidential Hopefuls

Congratulations on PAW’s thoughtful and timely piece on Princeton presidents and candidates. Especially apt was the juxtaposition of the quote from Bill Bradley ’65, the best qualified Tiger never to reach our highest office — “If people of idealism don’t go into politics, you abdicate that to people who misuse the system to their own advantage or will be ideologues that will polarize the country or more,” which provided the lead-in to the profile of Ted Cruz ’92. ’Nuff said.

stevewolock

9 Years AgoFor the Record

The family of Adlai Stevenson II ’22 owned The Daily Pantagraph in Bloomington, Ill. The newspaper’s location was reported incorrectly in a feature in the Oct. 26 issue.

Mary Adeogun ’13, whose photo appeared in Princetonians Oct. 26, works in merchandising for a women’s “workwear” company. Her employment was reported incorrectly in the photo caption.