Pastor Hampton Deck ’81 Has Become a Master Paper Marbler

The technique has roots in China and became popular in 15th century Turkey

By day, Hampton Deck ’81 has been the pastor of the First Presbyterian Church in Vallejo, California, for the past 28 years. But in his spare time, he preaches another gospel: marbled paper, the craft of covering sheets with swirling designs.

“I fell in love with marbled paper in Florence, Italy, when I was at the seminary,” says Deck of his visit to Il Papiro, a famous shop in the city that’s a major center for the art form. “And then, 29 years later, I learned how to do it.”

Deck, 64, who teaches marbling at Arts Benicia in the small Northern California town where he lives, studied with artisans in New Mexico and Istanbul in 2015 during a four-month sabbatical, using a grant from the Lilly Endowment’s clergy renewal program. It’s a future he could never have foreseen in his first job as an engineer working on a gas pipeline for the Florida Gas Transmission Company, right after earning his Princeton degree in civil engineering.

“I thought it was very beautiful and find it endlessly creative with all sorts of different patterns. I also love books — I have a big library, and like the physicality of books. I don’t use Kindle,” says Deck, who also studied bookbinding at the San Francisco Center of the Book, since marbled paper is often used in book arts.

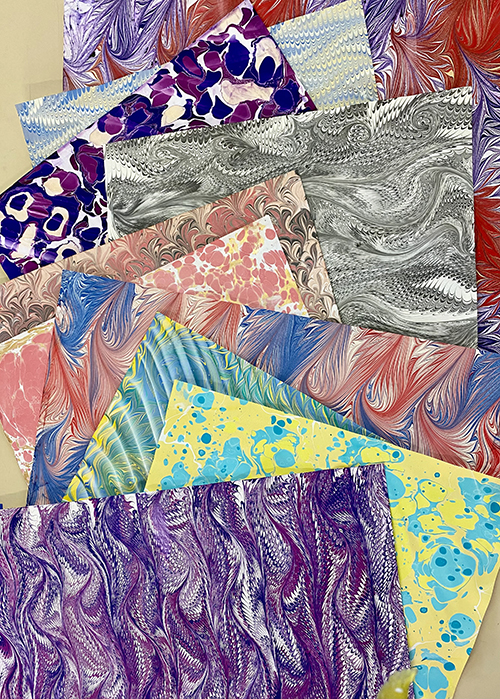

Deck gives a talk on the craft’s history, styles, and well-known artisans during his class. The patterns have names like Peacock, Cathedral, Scallop, Bouquet, and even New Jersey Ripple (invented by a Garden State artisan). The most basic pattern is called “stone” or “Turkish.” Marbling flourished for centuries in Turkey, and merchants brought it to Italy in the 16th century. But its origin is in China, it’s believed, and the craft spread to Japan in the 12th century, where it’s called suminagashi (“floating ink”), and Central Asia.

After throwing daubs of paint on a treated solution, Deck uses tools — combs, rakes, a stylus— to marbleize the paints. The colors don’t mix due to surface tension. Next, he places treated absorbent paper on the liquid, gently lifts the paper up, and lays it flat to dry. He makes some of his own tools and built a wooden tower with racks to dry the paper. He also figured out how to install a sink in his garage art studio himself.

“I have an engineering brain. I’m a curious person and like to know how everything works,” Deck says.

Raised mostly in Georgia, Tennessee, and Florida, Deck first sensed his calling to spirituality in junior high. He pursued engineering at Princeton and says it has helped with the mechanics of his paper craft, but ultimately he chose the spiritual life over the engineering life.

He attended Union Theological Seminary in Virginia for a master’s in divinity and the San Francisco Theological Seminary for a doctorate in ministry. First a minister at the First Presbyterian Church in Oakland, he became a pastor in 1995 in Vallejo. After growing up on the East Coast, he wanted to see what the West Coast was like, he says.

Deck studied paper techniques in Abiquiu, New Mexico, with master marbler Pamela Smith. “But she had very different tastes in color. I prefer brighter colors, which she called garish,” Deck says. After his studies, he made her a book covered with vivid red and black-and-gold veining, with silver and cobalt blue inside. Her response had a tone of complete ambivalence, he recalls with a smile: “Oh, Hampton, you’re really developing your own style.”

No responses yet