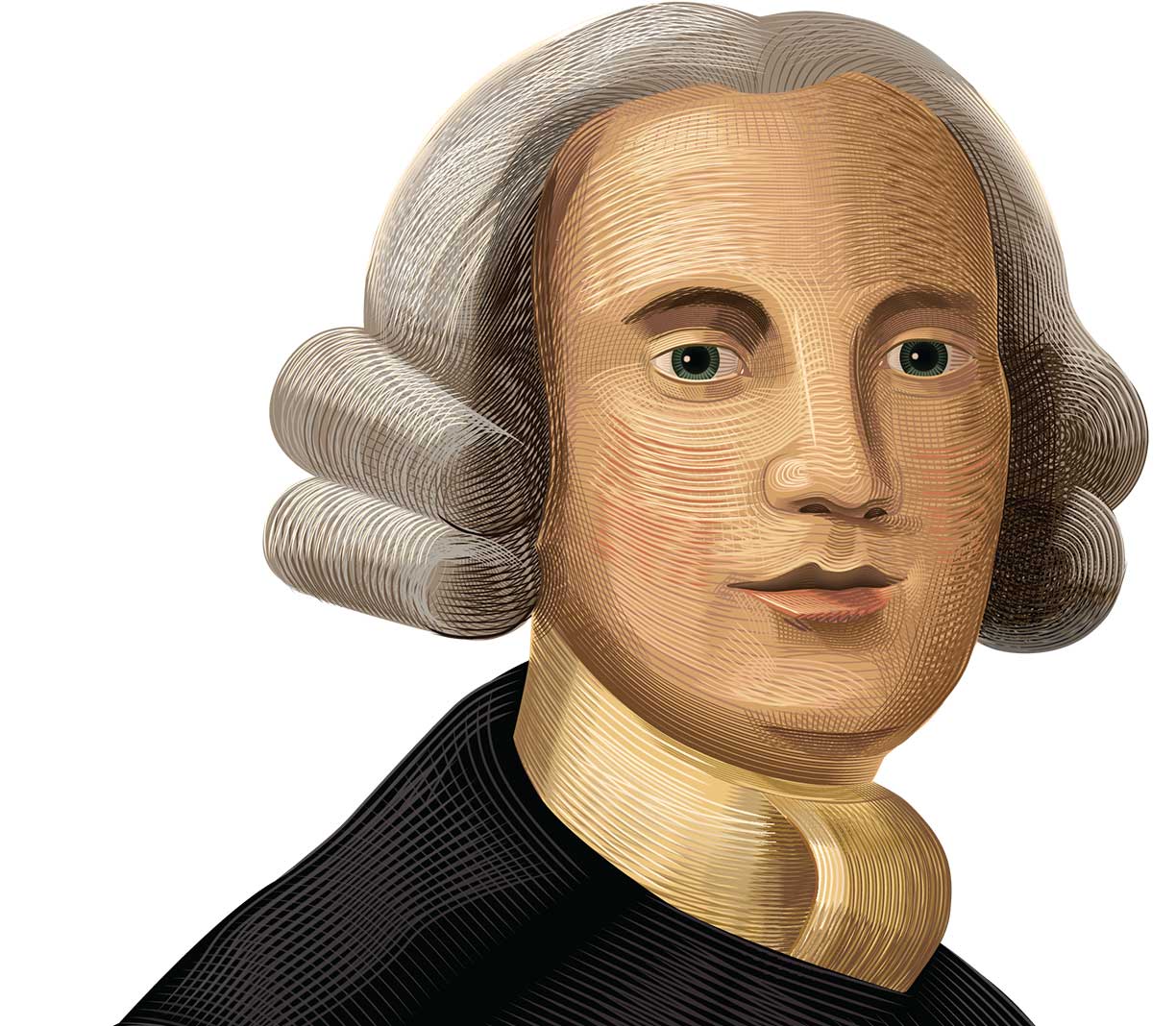

Three men from the College of New Jersey signed the Declaration of Independence: John Witherspoon, then president of the College; Benjamin Rush 1760; and Richard Stockton 1748. Six months later, in a British prison cell, Stockton recanted.

Stockton and his wife, Annis Boudinot Stockton, were a political power couple. She corresponded with George Washington and published poems that doubled as op-eds. He rose quickly as a lawyer, receiving his law license at the age of 24 and building a practice that spanned New Jersey, New York, and Philadelphia. In 1766, the trustees of the College chose Stockton to voyage to Scotland to talk Witherspoon into becoming the College’s president.

A decade later, Stockton was voted into the Continental Congress. The signing of the Declaration did not happen, even metaphorically, to a flourish of trumpets. Instead, the mood was tense, as Rush later reminded John Adams: “Do you recollect the pensive and awful silence which pervaded the house when we were called up, one after another, to the table of the President of Congress to subscribe what was believed by many at the time to be our own death warrants?”

Congress gave Stockton the task of traveling around the front to assess the condition of Patriot regiments. In October, he wrote from New Jersey, “The regiment is ... marching with cheerfulness, but a great part of the men bare-footed and bare-legged. There is not a single shoe or stocking to be had in this part of the world, or I would ride a hundred miles through the woods to purchase them with my own money.”

In November, while visiting a friend on the coast of New Jersey, Stockton was captured in a surprise attack and carried to New York. He languished in Provost jail, which was known for horrific conditions: starvation, freezing temperatures, rain and snow blowing through broken windows. Rush, who had married Stockton’s daughter, told a friend, “I have heard from good authority that my much-honored father-in-law, who is now a prisoner, suffers many indignities and hardships from the enemy, from which not only his rank, but his being a man, ought to exempt him.”

The British released Stockton in January. Gen. William Howe, the leader of the British forces, had offered forgiveness to any Patriot who signed an oath of fealty to the Crown. Stockton’s friends believed that he had signed the oath and judged him harshly for it. In March, Witherspoon wrote, “I was at Princeton from Saturday … until Wednesday. Judge Stockton is not very well in health & much spoken against for his conduct. He signed Howe’s declaration & also gave his word of honor that he would not meddle in the least in American affairs during the war.” All we can know is that Stockton received “a full pardon” from Howe, according to British documents, and that he left prison in terrible health that lasted for the rest of his life.

Stockton died in 1781, two and a half years before the Patriots won the Revolutionary War. He is buried by the Stony Brook Meeting House in Princeton.

3 Responses

Richard Stockton Weeder, M.D. ’58

5 Years AgoStockton’s Clerk

I was delighted to read the piece on my namesake (not a direct descendent; my ancestor, through both parents, was his aunt), but you missed what was, most likely, his most important role in history: Stockton was a direct link from the liberties Penn granted to his colony, through his law clerk, James Madison 1771, to the Bill of Rights. Stockton was a Quaker, as am I.

Lee Norris

2 Months AgoStockton’s Recantation

Richard Stockton was my great great (don't know how many greats, I am 90) uncle, and my mother's family was always immensely proud of the connection. I now learn of this man’s recanting of his signature on the Declaration, and I am appalled. And after the British treated him like dirt, they offered him a pardon for this dastardly act — and he took the Kool-Aid. He owned slaves, too. Down with his memory!

Norman Ravitch *62

5 Years AgoPatriotic Baloney

The American Revolution was pursue by crazed Calvinists in the North and South and by planters in the South who were heavily in debt to British creditors and wanted out. All the talk about liberty was bunk for the most part.