PAW Goes to the Movies: Professor Daniel Kurtzer on the New Moe Berg Documentary

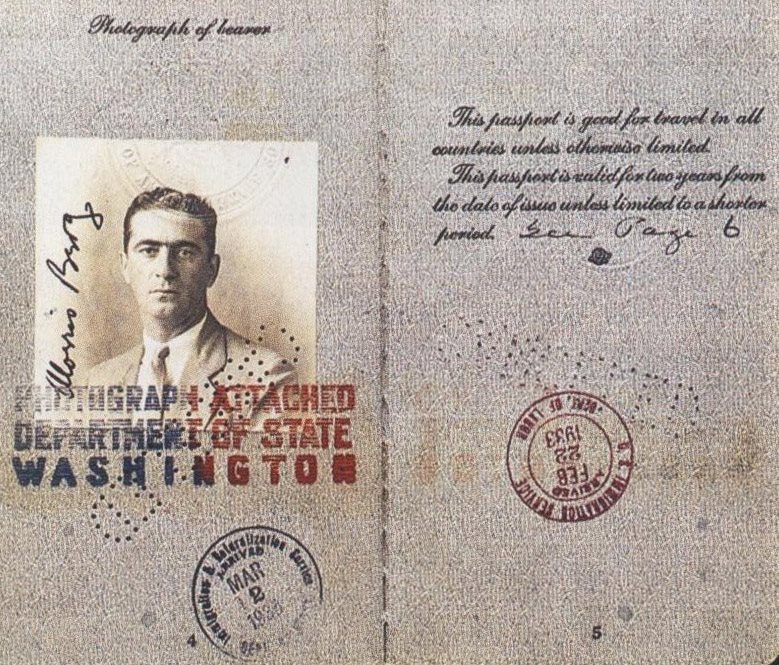

Lawyer, Major League Baseball player, respected linguist — Moe Berg 1923 was all of these things. He was also a spy during World War II. This multi-faceted, skilled, enigmatic man is the subject of a new documentary directed, written, and produced by award-winning filmmaker Aviva Kempner, The Spy Behind Home Plate. The film, featuring interviews with historians, Berg’s family members, and baseball players, writers, and executives, follows Berg’s life from his years playing baseball at Princeton to his time traveling in the big leagues to his covert career as an operative for the Office of Strategic Services, the precursor of the Central Intelligence Agency.

Visit TheSpyBehindHomePlate.org to find a screening in your area.

In another installment of our periodic series PAW Goes to the Movies, intern Jessica Schreiber ’20 sat down with Daniel Kurtzer, the S. Daniel Abraham Professor of Middle East Policy Studies at Princeton’s Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, to watch the documentary and discuss Berg’s roles as a baseball player and a spy. Kurtzer served as ambassador to Egypt and Israel during his 29-year career in the U.S. Foreign Service. A lifelong baseball fan, Kurtzer was named the first (and only) commissioner of the professional Israel Baseball League in 2007.

JS: What did you think?

DK: I thought the documentary was very well done. I think it’s much better than the film [about Berg] The Catcher was a Spy, which is made for a more popular audience. But this clearly involved a lot of research. What Aviva Kempner was able to do was also draw on some documentary film that was not used for what was supposed to be an earlier documentary that was never completed.

JS: You know a bit about baseball. There’s a famous quote about Moe Berg: “He can speak seven languages, but he can’t hit in any of them.” How true is that?

DK: Baseball is the toughest sport to master, I believe, because the physics and the skills that are required are so diverse. In a single player you have to have speed, you have to have the ability to hit the ball, you have to field, run … You know, Berg was not as awful a player as people made him out to be. His lifetime batting average was around .250, which today would probably earn him several million dollars a year as a backup catcher. But I think the expectation was that if you’re going to be hanging around baseball for, whatever it was, 18 years, you would be better than he. And he clearly was not going to be an all-star. It was never a question of his leading the league in hitting or anything like that.

JS: Does the film capture Berg’s life as a Jewish Princeton student at a time when few Jews attended the University, and as a Jewish baseball player, in a compelling way?

DK: It could have gone in either direction more deeply. You still don’t know much about his attitude towards Judaism or his own Jewish feelings except for that one vignette about the Princeton eating clubs, which does tell you that he had some sense of Jewish pride, as it were. [Berg was offered a spot in an eating club due to his athletic prowess, but it came with the condition that he not recruit other Jews. He turned the offer down.] You get a little bit more about his view of baseball — his willingness to play the game even though his father was opposed to it, and to stay with it including after he retired when he apparently frequently went to games and conversed with sportswriters. The film could have gone in a different direction and explored that more deeply, but you get a little bit of a taste of it.

JS: Why does there seem to be more interest in Berg these days?

DK: It’s hard to know. I think the combination of all these characteristics — baseball is the American game, he hung around baseball for a long time, he was a spy, had some successes, had this social ability both with women and with people generally — I just think it makes for an interesting character study. And those are the words you hear about him. Enigma. Closed. Just the idea that he answered questions with the finger over his lips saying “Shhh” — it leaves you thinking, “What was he thinking? Who was he really? What was going on behind the screen?”

JS: Our intelligence services have taken a beating recently. Do you think there are still people like Berg working in intelligence today?

DK: Shhh… You know, look. The intelligence business has changed so dramatically. We don’t need a baseball player on the roof of a hospital taking pictures in Tehran. Regarding the recent attacks on shipping in the gulf, we have film of what was going on. Some of it’s subject to interpretation but the technical capabilities of intelligence now are really quite extraordinary. That said, nothing will ever compare to human intel on leadership. And we probably still need people like Moe Berg who can get close to people on the enemy side or the adversary side and come back with a serious assessment of intentions and capabilities.

JS: What do you think is the most interesting thing about him?

DK: I like the baseball part, but that’s me. I think the most interesting thing is the enigma. At the end of the day, he probably was not the greatest spy and he probably was not the greatest baseball player, and there’s nothing at which he was superlative, but he was all of the above. That combination may be unique, or if it’s not unique there certainly aren’t many like him — and that’s what makes it such an interesting story.

1 Response

Stephen Rickert ’65

8 Months AgoBerg’s Language Skills on the Diamond

Moe Berg, Princeton Class of 1923, was a classmate of my father, Van Dusen Rickert. They were fellow classics majors. Moe was an excellent shortstop at Princeton. When an opponent stood on second base, Moe spoke Latin to his second baseman to hide the strategy they were communicating. Once, during World War II, he came to dinner at our house in Washington, D.C.