PEI Celebrates 25 Years: Princeton’s Hub of Environmental Studies Surveys the Global Challenges Ahead

As the 25th anniversary of the Princeton Environmental Institute approached, director Michael Celia *83 said its alumni had become “a fantastic asset to the world,” but he wondered if that was enough in the face of the Earth’s alarming environmental indicators.

“Somehow, the next generation of PEI needs to be thinking much more about how we can move the needle,” he said.

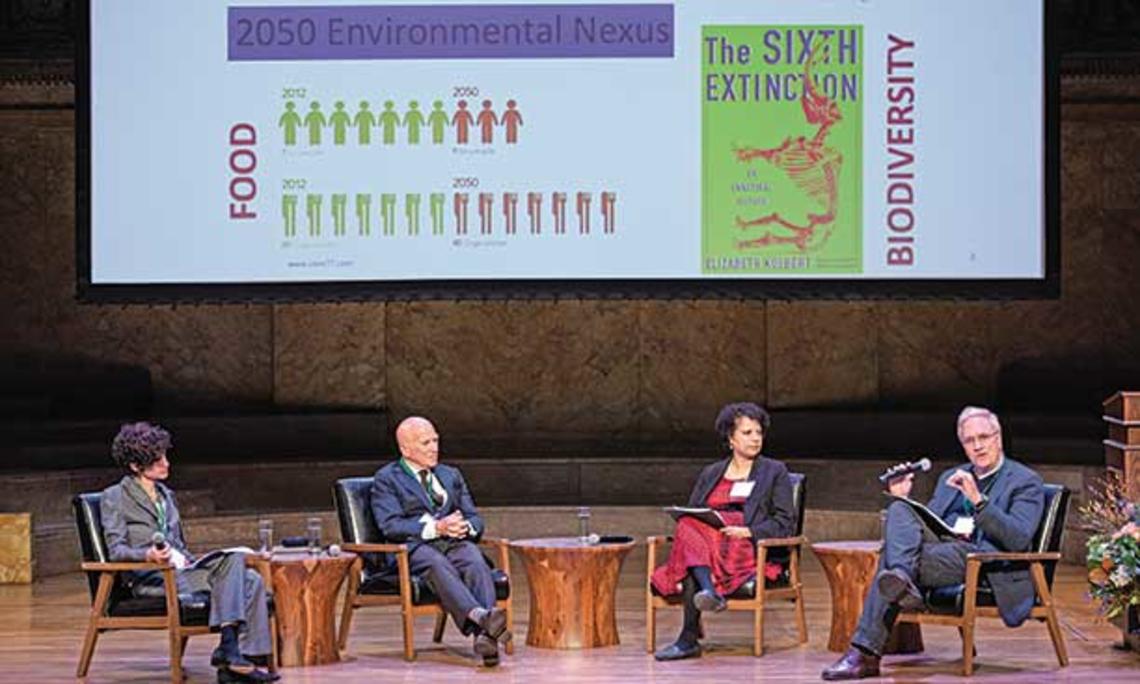

Days later, President Eisgruber ’83 joined that call, opening the Princeton Environmental Forum Oct. 24 to mark the anniversary. Moving quickly from celebration to action, he spoke urgently of environmental crises facing the world.

“Princeton’s mission of service to humanity compels us to make understanding and protecting the natural world a top priority,” Eisgruber said. “Given that the current environmental crisis is as much political, economic, and social as it is biological and geological, the world today needs a place like Princeton to bring these strands together to find workable solutions.”

That didn’t satisfy some of the students and alumni attending the forum. When Eisgruber took the stage in Richardson Auditorium, about a dozen audience members representing Divest Princeton — a new campaign calling on the University to divest its endowment holdings in fossil-fuel companies — raised orange and black “DIVEST” signs. Others unrolled a large banner with the same message in the back of the hall.

The demonstrators remained quiet, and Eisgruber later noted their respect for the University’s value of open dialogue. They did not interrupt his talk.

But the protest helped set the tone for two days of panels. Besides presenting science and ideas, panelists focused on politics, activism, and the role of academia in addressing the climate crisis, including the divestment issue.

PEI had come a long way from its early days of concentrating only on natural sciences. PEI professor emeritus Robert Socolow — a physicist who arrived to accept Princeton’s first environment-focused faculty appointment in 1971 — recalled that President Harold Shapiro *64 originally brought together researchers from fields such as ecology, biology, hydrology, and engineering.

With Professor Stephen Pacala, an ecologist, Socolow in 2004 co-authored one of the most famous papers in the carbon-mitigation field, the so-called “wedges” paper in Science that for the first time illustrated how a collection of existing technologies could bend the carbon-emission trend downward. The rapid advance of solar and wind power has made the paper outdated, but only after it shifted debate from theory to the practical task of addressing climate change.

“Important work has gone on here at Princeton, incredibly important work — the foundation of modern climate science,” said Kathy Hackett ’79, executive director of PEI.

After its beginning with natural-science expertise, PEI added social sciences, and later humanities, architecture and urbanism, international study centers, and even a journalist on annual appointment. The institute now connects 120 faculty members in 29 disciplines.

Celia said PEI’s mission today centers on synthesis, working on environmental problems by engaging across disciplines. A planned new building for environmental studies, scheduled to open in 2024 on Ivy Lane, will house the institute and the departments of geosciences, and ecology and evolutionary biology. It will offer both modern labs for natural scientists and collaborative spaces to bring together diverse ideas.

At the anniversary forum, panelists modeled that kind of exchange, grappling with the activists’ divestment proposal.

Pacala said divestment would be inconsistent with the University’s and society’s continuing need for fossil fuels. Carl Ferenbach ’64, an environmentalist and investor who served two terms on Princeton’s Board of Trustees, told the forum that divestment would be an ineffective strategy against climate change.

But Rob Nixon, professor of humanities in the environment at PEI, took an opposing view. “Princeton likes to be a moral leader,” Nixon said. “We like to think of ourselves preparing students for their future, but if there is no environmental future, then all other futures are moot.”

Robert Orr *96, a special adviser on climate change to the UN secretary-general, asserted that “the good of the planet and the good of the shareholders, or the stakeholders, is one and the same these days. ... It is not a good investment these days to be putting money into fossil fuels.”

The range of voices demonstrated PEI’s reach. Alumni filled the forum’s panels — an array of the world’s influential environmental minds.

Celia and other PEI professors pointed to these alumni as the institute’s legacy. Hackett recently surveyed PEI’s former students and learned that half remain employed in environmental careers.

But the meeting took hardly a moment to note this educational accomplishment. The problems at hand were too urgent to take time for back-slapping.

“We’re talking about existential issues,” Celia said before the forum began. “You cannot miss them if you keep your eyes open. No matter how much we’re doing, we need to be thinking about doing more. And that is the challenge that we face.”

1 Response

Blaikie Worth s’52

5 Years AgoOppenheimer’s Contributions

Excellent report (On the Campus, Dec. 4) on the Princeton Environmental Institute’s work, though where was mention of Professor Michael Oppenheimer, an early and essential contributor?

Divestment is always a thorny issue. The students are right; it should happen now, as a message from a powerful voice in the country.