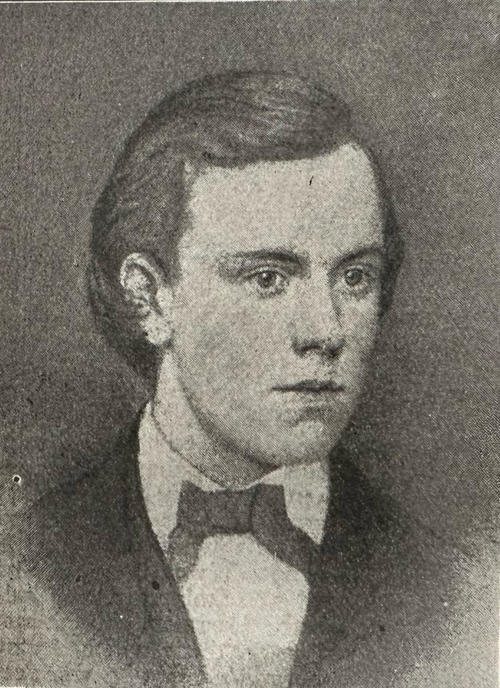

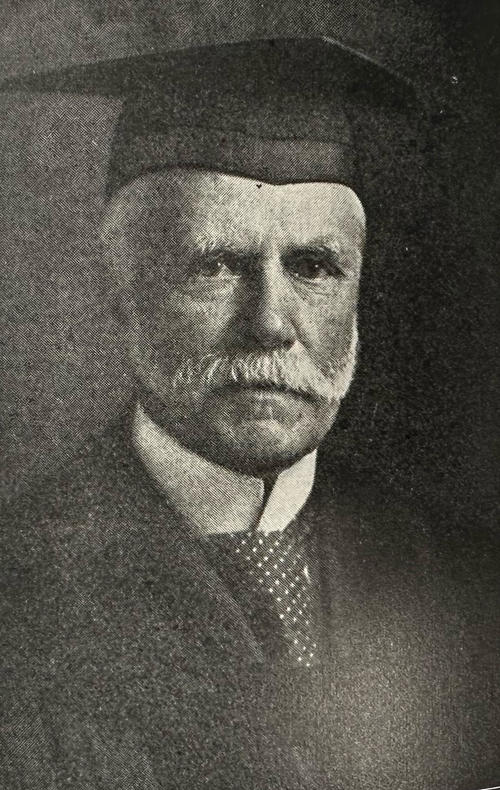

Personal Recollections of Princeton Undergraduate Life — From 1858 to the Civil War

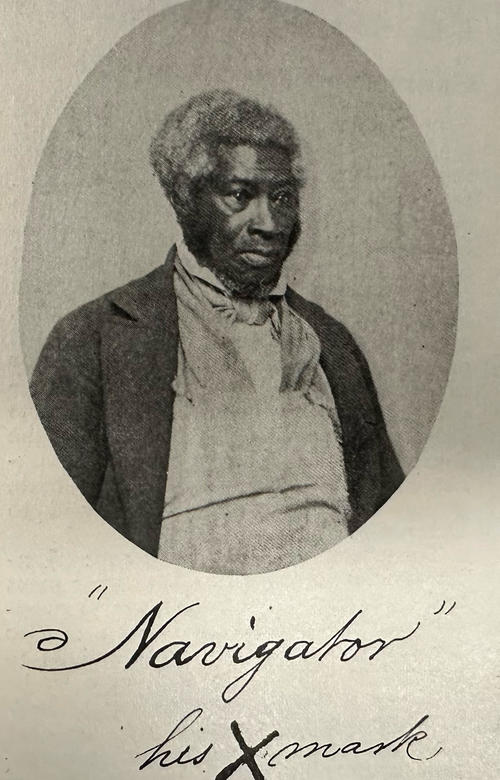

Editor’s note: This story from 1916 contains dated language in some captions that is no longer used today. In the interest of keeping a historical record, it appears here as it was originally published.

On the last Monday of June, 1858, I left Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, for Princeton. My journey began at eight o’clock in the morning and ended at the railroad station of Princeton at a quarter after five in the afternoon. You may cover the same distance now in about four hours. But at that time the railroads of the country had only about twenty thousand miles of track. Now they have about two hundred and fifty thousand. It would require more space than I have at my command to set forth the great changes that have taken place, in the interval, in the means of travel in respect of swiftness, comfort and safety. However, being only about fifteen years and a half old, I neither saw nor felt anything to criticize.

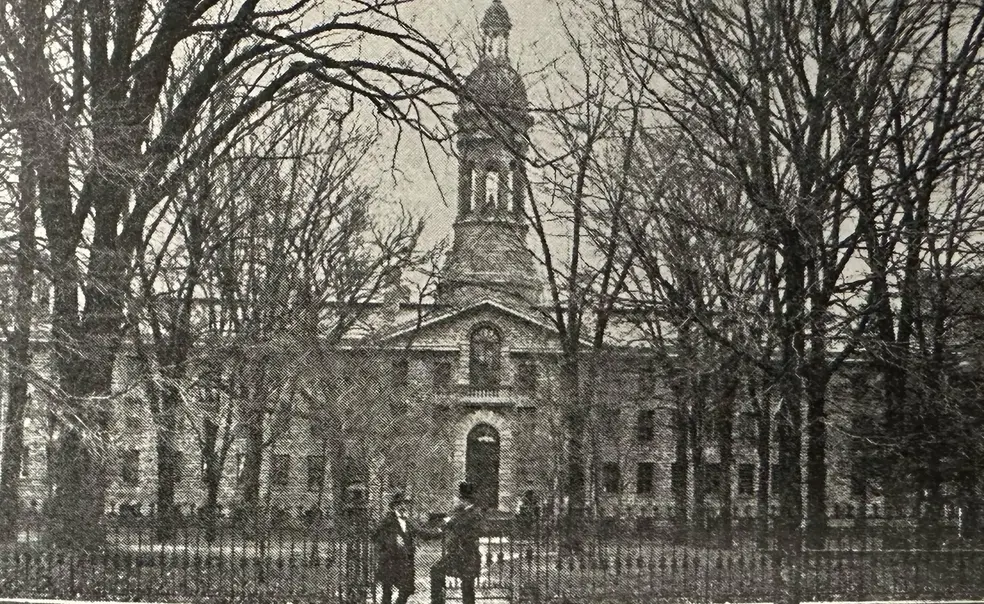

At the Princeton station, I was met by my brother of the Class of 1860, and we walked to his room in Nassau Hall. For an hour before supper, we strolled about the town. Except the buildings and grounds of the College and those of the Seminary, the two did not impress me favorably; chiefly, I think, because no street was macadamized; and, — a copious rain having just fallen, — the surface of every street was of the color and consistency of soft chocolate pudding and was made adhesive by the Princeton clay. But the campus and the college halls I thought great; and when I went to bed, I lay awake, I remember, for a long time, congratulating myself on the prospect — if only I could pass the entrance examinations — of being admitted the next day to the Sophomore Class.

The details of the examinations I do not recall. They were not long, and they were not severe. All were oral, except the examination in Mathematics, which consisted largely in my solving assigned problems. I called on each examiner at his house or room; and, in every case, great care seemed to be taken to allay my nervousness and to make me feel at home. The object of the examiner, so I then thought and still think, was to ascertain whether it would be possible to grant my application for admission. Nothing could have been more courteous or more friendly than the attitude of the members of the Faculty who questioned me. The requirements for admission to the Sophomore Class were fewer and lower than they are today, and the college authorities were far less rigorous in exacting them than those now charged with that duty.

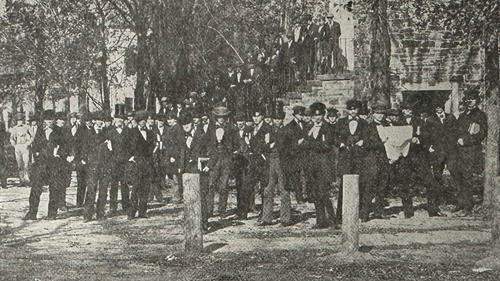

The examinations occupied most of the day, and it was about four o’clock in the afternoon when I was matriculated. Of my pride in my success I need not speak. Nor would it be appropriate to do so. This is not a chapter of an autobiography; but recollections of what the college was when I was one of its students. In the evening, I attended the Junior Orator exhibition. The First Church was crowded. This exhibition attracted and continued for some years longer to attract the great gathering of the commencement season. This was largely due to the fact that the eight Orators were not appointed by the Faculty, but were elected by their fellow-students. Young men, as a rule, are prouder of the favorable judgment of their peers than of the honors conferred as rewards of merit by a committee of the Faculty. There were some serious evils associated with the annual Junior Orators’ campaigns and elections; but, on the whole, the responsibility of selecting these representative speakers of the two literary societies it was wise to devolve on the students themselves. It did them good and it did the “Halls” good. I have the impression that it would be an admirable thing to revert to this “ancient custom.”

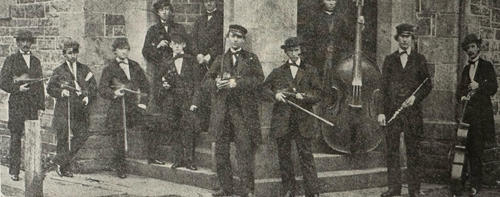

The Nassau Rake

The church was crowded to hear the Orators. Friends and strangers occupied the pews on the main floor; and the students filled the seats and the passage-ways in the galleries. After each oration, while the string-band was playing an interlude, the cry of “Rakes” was raised; and there sailed from points in the galleries over the heads of the audience below, octavo pamphlets of considerable thickness. These were copies of The Nassau Rake. This was an annual publication by the Sophomore Class, whose avowed purposed was to point out the defects of character and conduct revealed during the year by the members of the Junior and Freshman Classes. While this distribution was going forward, the President of the College arose and, in a high, querulous voice denounced the pamphlet as “scurrilous”; and threatened the editors and distributors with expulsion. This statement was received by the students with violent applause and boisterous laughter. For they knew well that Dr. Maclean was much freer in issuing threats of discipline than faithful in redeeming them. Whatever may be said of the President’s threats, his characterization of the Rake as “scurrilous” was eminently just. There is not apt to be delicate shading or any evidence of a sense of relative values in either the praise or the blame uttered by young students to and of one another. When they criticize their fellows they do so with emphasis and in the superlative degree. Of this trait of youth, the Rake was a striking illustration. The worst names were called and the worst faces were made. The book was not witty or humorous, though intended to be both. It was simply an exhibition of the thoughtless cruelty of the immature mind when moved to denounce others in fun. No other number of the Rake made such an impression on me as the one thrown that night to the audience. I am thrown that night to the audience. I am sorry to say that I thought it bright and interesting. But I cannot look at it now without imagining that its pages are exhaling a somewhat mephitic odor. Happily there is no longer a Rake.

On Commencement Day my brother and I returned to our home in Harrisburg, and did not see Princeton again until the beginning of the next session. The College opened on the 12th of August, 1858. Nowadays, the students and the Faculty of the University would regard a summons to begin work in the middle of August as “hard lines,” indeed. August is by eminence the month of vacation and travel, of crowded sea-shore and mountain resorts. But before the Civil War there were few people who left their homes in summer for more than two weeks. Besides, one-third of the students were then from the South; and of these not a few lived in the South Atlantic and the Gulf States. In view of this fact the College very properly provided a vacation of six weeks in the winter; and this provision made necessary a shorter summer vacation than the students now enjoy, and an earlier commencement of the autumn and winter session.

When I returned to Princeton in August as a member of the Sophomore Class, there were gathered about three hundred students. Of these, as I have said, one-third lived south of Mason’s and Dixon’s Line. The sophomore was the largest class. The catalogue gives ninety-seven as its number, but just after the catalogue had been printed a student was admitted, and tis actual number became ninety-eight. All of the students were candidates for the degree of Bachelor of Arts; and, with few exceptions, all were looking forward after graduation to courses which would prepare them to become members of one or another of the three “learned professions,” law, medicine and divinity. Princeton at that time had no School of Science, no School of Electrical Engineering and no Graduate College. As an institution intended only to teach courses leading to the first degree int eh liberal arts, it was large for the times. The students in Yale College who were candidates for this degree numbered I think about 350, and in Harvard about 400.

National Character of the College

Though the number of Princeton students was smaller than the number in either Yale or Harvard, we thought that Princeton College had a great advantage in the fact that it drew its students from an exceptionally wide area. This gave to it a national character. Harvard’s clientele was largely local. Yale’s had been more national until, in 1855 or ’56, members of its Faculty issued, on the Kansas question, a declaration very distasteful to its southern patrons. This brought more southern students to Princeton. Of the 302 students in the College during the year 1858-59, 107 were from the South. Of the students from the North, more than one-half were Republicans. They were full of enthusiasm, as became the young members of a new political party. The Southerners were always ardent, deeply interested in politics; and at this time they were quite bitter, owing to the successful organization and the popularity in the North of a political party devoted to non-extension of domestic slavery into the Territories, and scarcely concealing its determination finally to destroy that institution. Hence, political talk was frequent and exciting on the campus, in the dormitories and in the Halls. Its central and persistent theme was slavery; and this was discussed from every point of view; in its relations to the Bible, to the Federal Constitution, to society, and to economics. Events were soon to occur which made these discussions far more exciting. But I shall return to this subject later.

The members of the class as a rule were younger than students beginning the sophomore year are today. I have no complete statistics to guide me, but I somehow received the impression that at the date of graduation the average age of my class was a little over twenty-one years. The extremes were wide apart. My youngest classmate was graduated with high honors at sixteen and a half: the oldest, I think at twenty-eight. I know of five or six of them who completed the course before nineteen. One of these was the late Vice-Chancellor Emery, who, with another, had the highest general grade. As a body, they were more intelligent and more mature, I have the impression, than young men of the same age today; more accustomed to form and express opinions on large subjects, and with wider intellectual sympathies. But their scholastic preparation for the college course was not good in either the Classics of Mathematics. They were by no means so well drilled as the entering student now is. The secondary private schools, in the Middle and Southern States, were far less efficient than those which have taken their places, and the public school system, except in a few cities, did not prepare boys for college.

The Curriculum — Good but too Rigid

The curriculum of the College was a good one. Studies which discipline the mind were well balanced by those which cultivate it. These, with those devoted to the sciences, constituted a real course of study in the liberal arts; an admirable modern development of the trivium and quadrivium. I think, had they been living, it would have been praised by both Alcuin and Berengarius of Tours. Certainly, it ought not to be criticized by me. Though not one of the “honor men” of the class, it did me great good. How great, I did not realize until after graduation, when my faculties, instead of being, as I then thought, dissipated by too many studies, had, as I soon found, been strengthened and developed by my college course, and had been prepared, as they could not otherwise have been, for my professional education. How I could in any sense of the word have mastered the admirable definitions of Blackstone, and the subtleties and complexities of Fearne on Contingent Remainders without my Princeton life, it is not now possible for me to conceive.

There is only one thing to be said against the curriculum of that period. It was too rigid. It offered no “electives.” All students pursued the same course. When our Lord sent out his disciples, he gave them the liberty, if persecuted in one city, to fly to another. Our college authorities were far less liberal to their disciples. It was a grave mistake. Young men, as early as their college years, exhibit different tastes and aptitudes. Provision in the junior and senior year should have been made for these differences, even in an institution which offered only the Bachelor of Arts degree. The lack of this provision was unfortunate in two particulars; as regards the Faculty and as regards the students. Many men, at least half the class, seemed unable to understand the higher Mathematics. They failed to pass the examinations in the Calculus and to solve any problems which involved its employment. Many of these men stood high in the Classics, in Logic, in Natural Science and in Literature. And they were graduated. The faculty simply ignored their failure in this department. It would have been better if students in their junior and senior years had been given their choice between two higher courses in disciplinary studies — say, Logic and Mathematics. For, as it was, all students had to go through every examination. The sight of a written examination in the higher Mathematics was a notable one. About each able mathematician a group of students clustered, and quite openly and quite unintelligently copied his answers to the questions. Meanwhile, the Professor, Dr. Duffield, with a smile that expressed both charity and helplessness, looked on as if he did not see. In this way both teacher and pupils were made the moral victims of an impossible situation.

Of the Faculty, including the President, I should be glad if I had the space to write at length, especially of the professors. Every one of them was an able man and, in his department, a competent teacher. Unfortunately there was a public opinion among the students that forbade free intercourse between them and their teachers. It was held, if a student talked much with one of them, that he was “bootlicking for a grade.” The relations between them were not happy; the attitude of the students toward their teachers was rigid and even militant; though there was not one professor, I am sure, whom the students as a body did not respect and admire. Why nothing effective was done to remedy this evil I do not know. I am confident that the students because of it suffered great loss. Happily, a remedy has since been found in the preceptorial system.

Rigorous Laws — Lax Enforcement

The supervision of the conduct of the students was too detailed, as anyone may see if he will read the College Laws of that day. These regulations would have required a large staff of proctors for their serious enforcement. Moreover, far too large a proportion of them are merely negative. During my college life they were not vigorously enforced; but they were on the statute book, and ready to be quoted against any transgressor whom the Faculty thought it wise to summon before them. Of course, this detailed supervision provoked reactions on the part of the students. When they were forbidden to join secret (Greek letter) societies here, they accepted the hospitality of the same fraternities in other colleges; and so it often happened, that a student of Princeton was a member in another college of a society which supposedly had been destroyed. Horns were blown on the campus and fires were built around the cannon for the purpose of tempting the President and some of the professors to endeavor to catch the offenders. One day a calf cried out in the chapel gallery during prayers. On another the sophomore benches were plastered with molasses. Had the regulations been fewer, offences of this sort would have been fewer also. Meanwhile, nothing was done by the authorities to provide or even to foster athletics. Everything that was done was done by the students alone. It was to the initiative of members of the Sophomore and Freshman Classes that the College was indebted for the formation of the baseball club in 1858; and to the leadership of the Senior Class, were owed the erection and the furnishing, paid for by the students, of the earliest gymnasium in 1859.

This detailed supervision was extended by the Faculty to the students’ religion and theology. Attendance was compulsory, not only on Sunday Chapel, but also on week-day morning and evening prayers. In addition to these we had lessons in some of the disciplines of a theological seminary: Biblical Geography for Freshmen, a theologically conceived treatise on the Way of Salvation for the Sophomores, and courses in Apologetics for Juniors and Seniors (Paley’s Natural Theology, and Butler’s Analogy). All this in an institution whose charter contains but one reference to theological opinion, and that is, in substance, “no one shall be debarred from the privileges of education in this College because of his religious belief.” These classes we were compelled to attend. And we were graded in attendance and in recitations just as we were in the departments of Classics and Mathematics. I have a very distinct recollection of the influence exterted by this branch of the curriculum on the students. No studies were taken less seriously. In no other classroom was the behaviour more boisterous. The substance of no other courses — if indeed ever lodged in the memory — vanished so soon as this substance did. No other subjects seemed to the class of which I was a member to offer so many or such good opportunities for facetious remarks. I well remember that Dr. Guyot lectured to us on Geology the year we had the course in Natural Theology, and that he delivered an interesting and informing lecture on Cuvier and his work. In the recitation on the lecture he put to one of our brightest, and most fun-loving students, the question “Who was the founder of the Science of Paleontology.” And the student promptly replied: “The Rev. Dr. Paley. The science bears his name, and out class is engaged elsewhere in the study of his book.” The cheers of classmates can easily be imagined. The incident well exemplifies the attitude then prevailing toward our theological and biblical courses.

This behaviour was no evidence of disrespect for or disbelief in Christianity, or of a lack of religious sensibility. The voluntary. Meetings, intended to quicken religious feeling and to direct religious action, were well attended; and the addresses of those members of the Faculty who spoke were well conceived and highly enjoyed. But the close association of religion and theology with grades and discipline, in my day, was not a success. I am confident that the University is making no mistake in its progressive abandonment of the policy of my student days, and in encouraging the voluntary religious activities of the students in connection with the Philadelphian Society.

The “Mag.” and the Halls

The independent intellectual activity of the students showed itself especially in the two literary societies and in the Nassau Literary Magazine, then named popularly, not the “Lit,” but the “Mag.” I have refreshed my memory of the serious literary product of the student body, by reading into if not through the “Mag” of those days. I will not compare the two, but will content myself with the expression of my opinion that the literary product of our time need not fear comparison with the corresponding product of today. The thought was quite as mature, the subjects were as surely grasped, the discussion was as able and thorough, the literary form was as admirable as we find them to be in the current numbers of the “Lit.” To be sure, there are new models in prose and new meters in verse. But in the Mag and the Lit, the degree of inspiration and the mastery of form and the hopeful outlook and the fine idealism are the same; for though the fashions of the outer garments of youth change with the years, its spiritual vesture “abideth forever.”

Not, however, in the Magazine but in the two Halls the free intellect of the student body wrought most spontaneously; and often it wrought most violently. There, to their peers the orators delivered orations, and the men of letters read essays; and there, the rising lawyers and statesmen debated. It would be hard to make a present undergraduate realize the large place then filled by the Halls in the life of the College. Every student was either a Clio or a Whig, and was an enthusiastic one. During the years of my college life — certainly in Whig Hall — subjects and questions relating to current politics were those which awakened the greatest interest; for they were in our hearts, and by consequence, on our lips; not only in the Halls, but on the campus, during our walks and in our rooms. And so I am led — for I have little space left — to say something in closing about the southern students; their talks and ours with them on subjects which so deeply engaged their thoughts and feelings; and about their departure at the beginning of the Civil War.

The Departure of the Southern Students

They were a charming lot of young men — these students from the South. Of course, there were exception. I speak of them as a whole. Even if they were from towns, the spacious life of the large farms and plantations, and the habit of living as superiors in the presence of people recognized by all as inferior gave to them engaging manners. They conversed easily and well. If they happened to like you, they would talk freely and, as it seemed to me, in a judicial temper, about the peculiarities of the society in which they lived, and the political subjects of the hour. I may have been exceptionally fortunate in my particular acquaintances; but it is a fact that I heard from no one of them a harsh word, in private talk, about the North. But all of them, especially after the John Brown raid, were convinced that the North was determined to destroy slavery in the South. All of them believed the institution should be defended. They would hear no economic considerations against it. The harshest language I ever heard from one of them was a denunciation of a Southerner — the author of The Impending Crisis of the South. All believed in the right of secession; and, after the election of Mr. Lincoln, most of them began to say that the right ought at once to be exercised. Not a few, when bidding me good-bye at the beginning of the winter vacation, said that should their States seceded, they would not return to College; and of these, many did not. At its close in February, 1861, the number of southern students had fallen off greatly. The Southerners who were left were very quiet, and I am happy to say, that the northern students in their social intercourse were as considerate of their feelings as possible. I do not recall a clash even in words. On the other hand, as if anticipating their end, friendships became even closer than ever. At last the Union force was attacked, and Fort Sumter fell. One incident in the “Uprising of the North” was the nailing of the colors to the flagpole above the cupola of Nassau Hall. To the committee having the ceremony in charge came a representative of the southern students then in Princeton, with the request that they might be permitted officially for the last time to salute the flag. And one — John Dawson of Canton, Mississippi — asked that with his violin he might accompany the singing of the “Star Spangled Banner.” This was to be their farewell. The flag was raised. The salute was given. The southern students — not many, for the most had hastened home — then marched off the campus, the northern students standing uncovered before them at salute. Before the next day the most of them had gone.

Senior examinations soon commenced. At their close, six week I think before Commencement, the Seniors left. The day I returned home I began the study of Law. I came back to Commencement, spoke my piece and received my diploma. The tragic breaking up of the class was depressing, and I soon left the town. But on my way to my home I remember thinking of the College with admiration and of all it had done for me with sincere gratitude. The next morning I took up again the study of Blackstone.

This was originally published in the March 22, 1916 issue of PAW.

No responses yet