Personal Recollections of Princeton Undergraduate Life — The College During the Civil War

Part II

Editor’s note: This story from 1916 contains dated language that is no longer used today. In the interest of keeping a historical record, it appears here as it was originally published.

So far, I have limited this story almost wholly to Princeton as the College was related to, or involved in, the war of the Union. But, of course, during those years the undergraduate life had interests which, in many ways, were quite apart from the national struggle. These recollections would be altogether inadequate were I to ignore those interests. Much that I remember has been, in effect, already told, by others, yet some of my memories have a value sui generis.

The two Halls, Whig and Clio, passed through critical experiences in the early “Sixties.” The whole body of students, with but few discreditable exceptions, was divided by membership in the two Societies. The Societies were originally intended to be wholly literary in character, aiming particularly at forensic discipline. And, beyond question, they had for many years given a marked impulse towards a larger intellectuality and to a practical skill in discussion of social and civil questions on the part of the Princeotn graduates. The training received in them in literary expression, in oratory, in debate and in familiarity with parliamentary procedure had made of the Halls, schools from which were sent forth some of the most useful and successful of America’s public men. A story current among us was that once about a third of the leading debaters and legislators in the National Congress had been “Whigs” and “Clios.”

But in the early “Sixties” there seemed to culminate certain untoward influences in the Halls which certainly tended to injure their historic usefulness. Probably the restless and aggressive partisanship which pervaded all American life at the opening of the Civil War was chiefly responsible for this marked aberration. At any rate, during the years of the war there was an intensity, an extravagance, indeed a degeneration of Hall politics, both within the Halls, and by the separate Hall men in the class rivalries, whose influence upon the students was harmful. For instance, in one of my three years the annual campaigning for the posts of Junior Orators — four speakers chosen in each Hall to deliver “The Honorary Orations of the Junior Class,” at great gatherings of the students and their friends, — became so absorbing, and it evoked so much hostile partisanship, that the Faculty resolved to change the conditions governing the elections. Whig Hall was especially involved, and the Whig members of the Faculty — the societies being secret organizations — undertook to secure the change which was thought needful. Much antagonistic feeling was aroused among the students over this effort. I do not remember just what result was effected, but I have a published comment of the time which assisted that “should the Halls become mere appendages of the College, under the immediate government of the Faculty, our interest and our pride would vanish together.”

Memory is dim now, but I can still bring to my mind’s eye scenes on the floor of Whig Hall, whose persistent turbulence went far to justify the solicitude and the interference of the college authorities. Nevertheless, generally speaking, the opportunities and the discipline gained by the work of the Halls did much to fit Princeton youths for their future as members of some of the professions, and especially as active citizens of the Nation. No other college of those days, I think, equaled Princeton in the preparation of ready debaters and parliamentary workers. Moreover, the liberties of both Halls were excellently furnished with standard works in history, philosophy and belles letters, and quite a number of the boys were ambitious readers of the celebrated books.

There were, also, at that time, several Greek letter fraternities, holding the allegiance of many of the students, although forbidden, and soon to come to naught. Almost of necessity, under the circumstances, these fraternities were subjected to the intense partisan rivalries which then excited the undergraduates.

Campaigning for Class Day Appointments

The excesses which affected the campaigning for the “Junior Orators” also appeared in each Senior Class in the selection of their Orator and their Poet for Class Day; also, in a measure, their appointment of the editors of “The Lit.” Personally, the struggle over the Orator for ’64 is memorable for the reason that for weeks the canvassing did not break a “tie” that had been made and my vote was as yet unannounced. I had been named for the position of Poet, with no opponent. But I felt compelled to cast my vote for one as Orator who was not favored by my special political friends. For a long time I would not name my choice, despite much solicitation, hoping that, in some other way, the “tie” over the two orator candidates would be broken. But both sides were fixed. At last I had to speak; thereupon, knowing what strong feeling would follow my announcement, I coupled with that a declination of candidacy for the honor of becoming “Poet.” For awhile I was a very lonely youth. My disappointed friends, however, at length did me ample justice. I wrote the “Valedictory Ode.” I was also made chairman of the Editorial Committee which founded and issued The Nassau Herald, now long of useful service at Class Days.

In passing, it may be of interest to note that during my undergraduate days “The Rake,” an occasional publication of notorious fame; addicted to a merciless scoring of the Faculty and students, did not appear, at least as I think, but we received, in its stead, in two, perhaps more, issues, a miserable substitute, really a disgrace to the College, named “The Whang Doodle,” which “mourneth for the Sophomores,” but was, in fact, four pages of well written yet cruel ridicule, directed against certain members of the Faculty and many members of both the “Soph” and the Senior Classes.

One harmless fad in the early “Sixties” deserves recall now. A craving for mutual appreciation, very natural in such a body of segregated and closely associated youths as were those of Princeton in those days of comparatively small things, found gratification in the circulation of books nominally for autographs but really for the writing of from one to a dozen pages of personal reminiscence, and of friendly or even of affectionate tribute. During the senior closing term, these books went from hand to hand, with assigned pages in them, for each chosen recipient. A rather cynical college mate wrote of this fad, — “It is astonishing what a number of scholars, patriots, orators, statesmen, etc., are to be let loose on the world.” Childish though the autograph fad was, I prize even now the well-filled books of one “mutual admiration society” that came to be my portion at graduation.

War-Time Athletics

But what recollections have I of Princeton athletics and of the college games? Of course, comparatively speaking, my memories of these things are of what was very insignificant and crude. But we had, back of West College, a good-sized gymnasium, built, I think, in 1859, independently of college help. At the noon hour, especially, the “gym” was a very livel place, with many of us using the horizontal and parallel bars, ladders, ring-swings, dumb bells, and the spaces for jumping, and for the lifting machines. I think that the “Handball Court” was still there nearby. Fencing, boxing and wrestling were a good deal in vogue. And athletic training in a rude way was furthered by several among us, namely by regular noon use of the “gym” and sunrise runs down across the canal and away for two or three miles out, and then back, the last half mile an uphill run. In the evening, after chapel, long, leisurely-made walks were indulged in. My frequent preference was for a walk out Witherspoon Street to “Rocky Hill.” I knew of a big, wonderful rocking stone out there that attracted me. Often, too, I preferred the woods south of the College, where there was a beautiful pond to sit by for meditation at sunset.

In those days baseball was becoming quite “the thing” in the college games. In ’61-’62, the “Nassau Base Ball Club,” organized in 1859, began to have widely aggressive aspirations. The first real match game that I remember was played in the spring of 1862, between the “Nassaus” and the “Seminoles.” In the six innings played, the “Nassau” scored 45 runs to 13 by the “Theologs.” It is of record that in October, 1862, “the military are not the only objects of curiosity in our little college world. Champion Base Ball Clubs, Wonderful Gymnasts, etc., go to make up a pleasing group of curiosities unexcelled, we are sure, by any other institution.” In that month a game was played at Princeton between “The Star of New Brunswick,” and the “Nassau Base Ball Club,” wherein, “The Nassau — as usual — was ahead and the game was ours.” “And now, in virtue of its final triumph over the champions of New Jersey, the Nassau Baseball Club, like the Nassau Cadets, stand boldly forth, the admired of all admirers.” In the next year, 1863, Princeton’s later celebrated career in the national game seems to have been really entered: “All honor to Old Nassau! In the contest between the first nine of Nassau and the Resolute, Star, Excelsior and Atlantic Base Ball Clubs of Brooklyn, the result is a series of triumphs for the Nassaus, terminating in a brilliant victory, with one exception; — the game with the Atlantics, which had only seven innings, — score 13 to 18 — when the game was called because of darkness.” I learn that in the following spring, at Philadelphia, the “Nassaus” conquered an “Atlantic” Club, apparently a local organization. Then, in the autumn the Nassaus challenged all the colleges of the country to a test. Princeton was thus early among colleges in taking the lead in this game, which for a half-century she has made her constant aim, with many honorable successes.

During the Civil War, the great game of football was not played in ways that deserve praise now. We kicked a big, inflated ball about the grounds near the “gym;” but as a real game the sport amounted to nothing. Systematic track athletics was, as yet, something unknown among us.

Hazing and Horn-sprees

Naturally, there was a sportive or frolicksome side to our undergraduate life. The religious revival of 1861-62 did temper the fun and mischief-making of the boys for that winter, yet hazing parties had their festivities in each autumn. They were of no great violence; and, excepting in cases where a full does of the “medicine” was adjudged needful, the hazing was good-naturedly given and accepted. I remember that our dear President did once advise resistance even “with a club” on the part of men hazed, but his advice was only the signal for a boisterous scraping of feet among his auditors, whose immovable shoulders and heads were no telltales of their noisy shoes. Also, we had at least one horn-spree during my student days, when the town was surprised by the foray of a group of fancifully disguised revelers who made the night hideous with shrieking tin horns. That night the good citizens had their gateways, shutters and business signs ridiculously misplaced. Quick penalties followed discovery and arrest, but now and then tradition had to be maintained, and the loyal plunderers would sally forth. The old battle-cannon, too, had to take part upon occasion by growing hot because of a mass of blazing boxes, barrels and other inflammable stuff piled on and around it. I am reminded now of one rather exuberant simulation of a horn-spree that caused quite a talk. A half dozen very lightly clad boys one winter night made a swift, silent run to Lawrenceville, where there were special festivities at the girls’ “Seminary.” Fiercely blowing horns, the young roisterers encircled the illuminated building, to the evident delight of the young lady students, who crowded with their escorts to the windows to see the wild “serenaders.” Twice around the building the frantic youngsters pranced, Indian-like, howling and tooting; then, off into the darkness towards Princeton they sprinted, leaving, however, along their way a sort of “chaos come again,” among gates, door-steps and several other things portable.

Another “frolic” at times thought advisable, especially by seasoned “Sophs,” was the “smoking out” of boys just from home and therefore very “fresh.” An attempt, however, in the autumn of ’63 to “smoke out” one new-comer miscarried so badly that it was long before the victims were released from the chaffing following their defeat. The newcomer had taken one of the “Barracks” rooms of East College. These ground floor rooms were usually occupied by Freshmen. This new roomer, however, was really a Senior staying in the “Barracks” until his third-floor room could be refurnished. He was a returned soldier, having had a year of “experience at the front.” Not knowing of this fact, the “soph” disciplinarians considered him worth their attention. One night they took him in charge. They were received courteously by their victim, who at once understood the purpose of the visit. When asked what class he was entering, he answered, “the first.” He meant “Senior”; they understood, “Freshman.” Did he “object to smoking?” “No! if the tobacco is good.” “Cool evening; may I close the windows?” “If you please.” Then the fun began. The room soon was dim with the rank fumes. But the smokers gradually began to be troubled; some evidently from within, but at last one of them because of the sudden recollection that he had seen their victim at the preceding Commencement as one “returned from the wars.” Manly, despite his mischief, he humbly begged the amused Senior’s pardon, much to the dismay of his comrades, most of whom by that time had no further desire to puff their pipes. The would-be jokers were magnanimously forgiven, but it was many a day before the other boys allowed them to forget that they had tried to haze “an old soldier” by a “smoke-out.”

An epidemic of cane carrying and carving that spread among the undergraduates in those days in worth a note. Canes, big and little, graceful and ugly, slender and stout, became treasured personal property, and many hours were spent by the boys in passing canes about for the carving of their names on the memorable sticks.

The National Concert Troupe

Music, too, had many devotees. Chapel and church choirs were made up of students. And in 1862 there was, in fact, an excellent orchestra, composed wholly of undergraduates, which at times was substituted at public college exercises for the bands usually hired from Trenton and other distant places. There was a group of singers and instrumentalists among us who called themselves “The National Concert Troupe,” who made a memorable trip to a town twenty miles away to give there a “classical concert.” The participants were all disguised and presumably were from New York City. They had a large audience in a capacious auditorium. Their performance was in fact not at all bad. Probably all would have gone through as was intended, had it not happened that one of our “professionals” was recognized because of his voice, by a cousin who was attending the girls’ academy in the town, and who was among the auditors. “They are Princeton boys,” speedily went through the throng. One can imagine what the rest of the entertainment became. But good nature prevailed. Disguises were laid aside. General good fellowship followed the “spree.” There was a late supper at the town hotel, paid for from the proceeds of the entertainment. And then an unforgettable midnight ride back to Princeton was taken, —

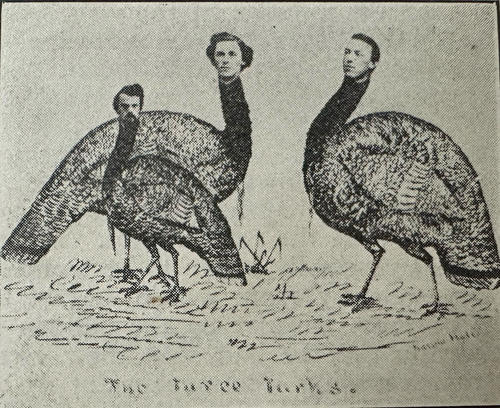

“When the N. C. T.’s stole some turkeys off the trees.

Of the sleeping rustic dwellers by the way, by the way,” etc., etc.

A few days later, when these turkeys had been prepared “down town” in Princeton, for a brigands’ banquet, by some college vandals who had stolen them from the midnight raiders, there was a “near riot,” which almost became the real thing. The whole affair, however, ended happily at last, and I think that the despoiled farmer also was quietly well paid for his lost “gobblers.”

Much more could be told of the frolic side of our undergraduate life during the Civil War, but the stories would not be peculiarly distinctive. Every period and class has its own, and quite kindred, adventures and escapades. I mention this much of the fun and mischief of the “Sixties” chiefly that it may show how closely the students were then associated, and be, in its way, an indication of the general camaraderie or inworking of the Princeton spirit in the student body as far off as a half century ago.

Moreover, looking back now, and recalling our undergraduate life in all its aspects, I see clearly that, allowing for all that I have just said, the dominant influence it exerted was for good; that, so far as character was being formed, we were receiving, on the whole, that which was helpful towards a true manliness. One of my classmates, writing at the time in answer to certain criticisms of the fun-making which had its way among us, and “parents sometimes hesitate about sending their sons to college, fearing a rapid degeneracy and destruction of their moral economy. Such parents unconsciously acknowledge a decided weakness, or what is often the case, the worthlessness of their offspring.” To this youthful judgment I am willing to add the comment that, were there any of our mates in danger of “going to the bad,” it was because they were themselves at heart evil. Those men would have gone “to the bad,” college or no college; and, I am confident that they would have gone to the bad more quickly with “no college” than with such a college as Princeton was in the “Sixties.”

But I must bring these recollections to a close; yet I may not do this without some reference to the personnel of the Faculty which had the College in charge during the eventful years of which I write.

The War-Time Faculty

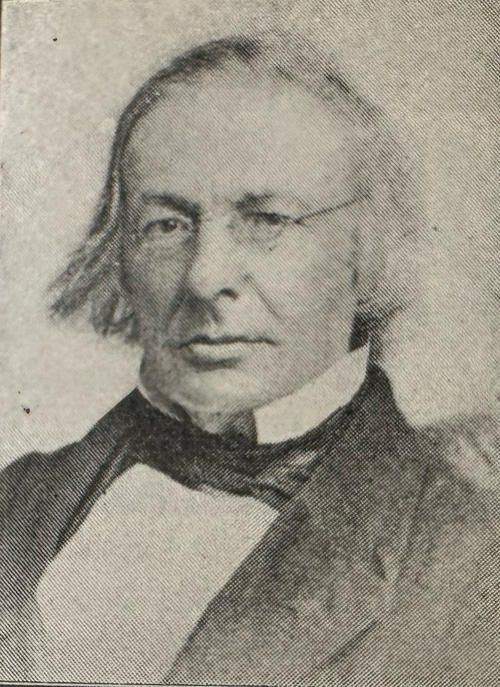

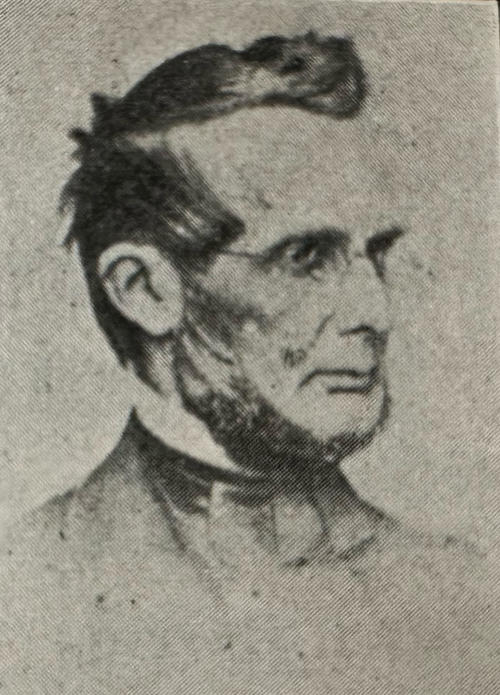

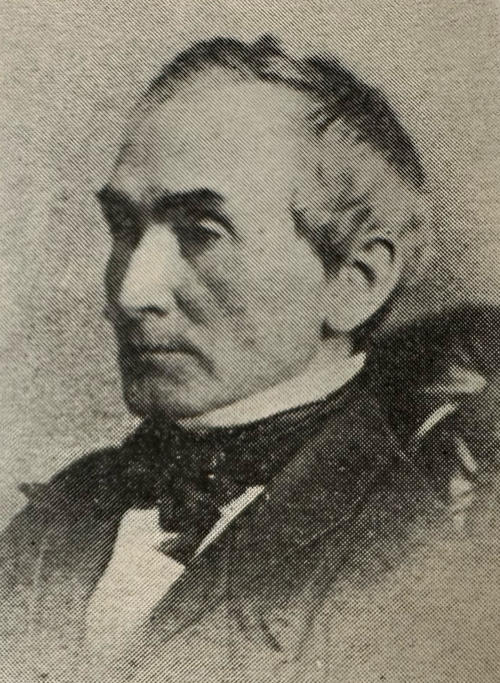

As I recall our Faculty they reappear to memory as teachers well fitted for their departments, all doing their work well. Close personal intercourse was not common between the professors and the students, but I happened to be exceptionally well acquainted with Professor Duffield and Giger and most so with Professor Guyot. Dr. Maclean I remember as always approachable and lovable. Professor Cameron was a rather austere teacher, but, at times, I knew him in ways that were quite genial. Dr. Atwater was far from being the exacting and oppressive personality that official contact seemed to make of him. And Professor Alexander appeared to be far apart from us, to have his common dwelling-place among the stars he loved so well. If at times the association he had to have with us in the classroom seemed execrable to him, and he gave vent to his feelings, the boisterous responses he received were really more a display of affection than of antipathy. The boys loved to hear “Stevey” scold, and they were personally proud of association with the man who stirred in all who heard him “the sense of the sublime” with his famed lecture on “The Nebular Hypothesis.”

Were I to characterize our Faculty with adjectives, I think I could get a majority approval from my fellow students by naming them with these tributes: “Dear old Johnnie,” our President who answered examination questions for us, by the way he asked them; “Easy Duff,” whose “therefores” in his demonstrations in mathematics were a sort of A. B. C. in instruction; “Genial Gige,” who led the way in Latin so that we had only to follow in order to “get there;” “Charming ‘Wocks’” who made poems of his beloved rocks (“wocks”) and a fairy story of “Earth and Man;” “Stevey,” whom it was our delight to tease, and yet deeply to revere; “Cam,” whom we feared yet respected; Dr. Atwater, whom we petted as “Dad,” and yet served with a sort of awe, until the time for his annual pleasantry to the Juniors, when, thrusting his big hand forward on the shining top of his lecture table, he gravely asked, “What is matter? Never mind. What is mind? It’s not matter. And what is Spirit? It’s immaterial.” Hereupon, the annual response came from the class, —- a stamping and varied applause which “Dad” never could still, yet which he knew was sure to be let loose in that lecture. In passing, I think a little joke of which Dr. Atwater was the subject is worth remembering. One of our boys was very clever at pencil caricature. Dr. Atwater was physically large; and he had a head whose shape gave pleasure to our cartoonist. The artist drew, as lying upon a plate, a pear featured as Dr. Atwater’s head was featured. The likeness was excellent. The picture was photographed, and, as a card, was circulated for the delectation of some of the boys. One morning, a possessor of the picture met a son of Dr. Atwater’s on the campus. The student mischievously showed the card to the child, who exclaimed, “Why, that’s a pear!” “Yes, my son,” was the reply, “It’s your pere.”

Professor McIlvaine was known to us just as “Josh”; and our feelings were rather neutral concerning him. He was comparatively new to the College. Dr. Moffat was much admired. We had no familiar name for him that I can recall. Likewise, we did not think, or speak, familiarly of Dr. Schanck, or of Professor Hope. Professor Henry, who had been transferred to the Smithsonian Institution and yet was by name connected with our Faculty, though not one of its working members any longer, was to us a man bearing honors unsurpassed by any other scientists. We were, in good measure, proud of being Princeton men because this great man’s fame shone about the College.

I was graduated as a member of the Class of ’64. But circumstances had associated me with both that Class and its predecessor, — so closely with the latter that throughout my life I have felt an allegiance, which, with a twofold name, has had but one loyalty. I am an alumnus of Princeton, belonging to both ’63 and ’64. And I am especially gratified to have had the privilege of putting these recollections of “Undergraduate Life During the Civil War” upon record, as a member of the two classes whose careers were so intimately associated with the stupendous crisis through which the American Nation was delivered from the greatest peril in its history.

Members of President Maclean’s War-Time Faculty

This was originally published in the November 22, 1916 issue of PAW.

No responses yet