Personal Recollections of Princeton Undergraduate Life — The College During the Civil War

Part I

Editor’s note: This story from 1916 contains dated language that is no longer used today. In the interest of keeping a historical record, it appears here as it was originally published.

I wish that memory were magician enough to disclose for me the Princeton of fifty-five years ago so fully and clearly that these notes would be worthy of those memorable days. I cannot make that wish good; but, as I look backward towards the early “Sixties,” many person and events of the time reappear. Probably a record of what I am seeing will help somewhat towards rounding out the very valuable history which The Alumni Weekly is now gathering of Princeton’s near past.

Welcoming the Freshman

I remember myself as a boy of eighteen, starting out one mid-summer morning from the old Mansion House, accompanying a relative, an alumnus of about ten years, on the then customary round of visits to a half-dozen of the college professors, for a test of qualification for a place on the student roll. In a few hours I had passed under the searchings made by Professors Duffield, Cameron, Geiger, Atwater, and President Maclean, and was ready for enrollment in the Junior Class, — the Class of ’63.

The dreaded rigor of the test, to my surprise, had met me nowhere. All the examiners seemed to make rather a social affair of they duty, — all of them, so I think, having been friends of college associates in former years, of my accompanying uncle. Probably, too, the fact of my having come from the Junior Class of Dickinson College made this examination, in large measure, the round of social visits it seemed to me to have been. However, in 1861, I became a Princeton student.

It is not needful that I should repeat my memories of the general physical appearance of the College then, nor of the limited and inflexible curriculum then imposed upon all the undergraduates. That has already been done by those who have written of their own times for these “Recollections.” During the Civil War there was no change made in the campus, in the buildings, or in the course of studies which had been long distinctive of Princeton. The ways of the past were faithfully followed throughout my connection with the institution; indeed, I believe, until the strong will and original plans of Dr. McCosh had become authoritative.

My part of this story of the college begins where John DeWitt’s (’61) admirable recollections of the years “Form 1858 to the Civil War” were brought to a close, — soon after the outbreak which threatened the National Union, when almost a hundred, or approximately a third of Princeton’s students, whose homes were in the Southern States, had left the College.

Campus Sentiment at the Opening of the War

My Princeton career began, consequently, when most trying experiences had befallen the institution; when the authorities had seen a portentous lessening of the number of their students, and, with much serious misunderstanding on the part of the public, had striven against it. Princeton had become distinguished among the colleges of the Northern States as a place where the boys of the South could find an especially congenial home. And it is true that the administration of the College had been quite conservative, or rather neutral, in the midst of the growing political discussions and alienations affecting the American people then. Because of this fact there happened a very unpleasant, and, for awhile afterwards, a rather harmful incident accompanying the excitement following the attack upon Fort Sumter. In “Princeton Sketches” I note this pertinent passage: “Princeton had always an unusually large constituency in the South, — more so than any other northern institution. Naturally, the intense political feeling of the time found its expression among the students, and heated arguments often led to arguments of a different kind. A national flag which had been run up over the belfry of Old North was taken down by order of the President. The Faculty, although thoroughly loyal to the Union, endeavored to keep the peace of the College by preventing conflicts which might lead to disorder.” The lowered flag, however, was soon raised again. An overwhelming demand for its restoration was made by a large majority of the students, to whose support an aroused community rallied. And the Faculty in large measure gave over its vain effort to maintain neutrality in the Nation’s interstate struggle.

I remember well the mood of the College which followed this episode. With the reopening of the session in August only students living in the Northern States were present; and dominant over all else was an ardent devotion to the Union, made fervid and very exacting by the disastrous battle of Bull Run, and the great rally of the North at the call of the country’s President. The Faculty, so we all understood, had given an outspoken support to the Union. The whole College was tense over the varying fortunes of the increasing conflict.

“Pumping” a Student

Then it was that an even came to pass in our little world which, probably more than all else, was significant of the feeling pervading the student body, and became decisive of the political attitude which Princeton memorably bore thereafter in the Nation’s struggle for life.

The legitimate “Sons of the South” had all gone to their homes; but there happened to be among us quite a number of “Sons of the North” whose sympathies were with the seceding States, and who had not yet learned the lessons of wisdom and prudence needful in such surroundings as theirs. One of these youths was unpleasantly and persistently aggressive; and he was too obtuse to heed the signs of the times often shown him. At length, when he had openly expressed pleasure at some disasters which had befallen the army of the Union, and spoke of hope that the cause of secession would triumph, he went farther than the toleration of many would allow.

One night, towards mid-September, a group of fellow students entered the room of this obnoxious associate, dragged him from his bed and, with no pleasant ceremony, haled him to the historic pump back of Nassau Hall, and there thoroughly drenched him with its cold stream, thus making, as a newspaper record of the time runs, “a public example that all might learn that our Union-loving community would be thus outraged no longer.” Three of the students of the pumping party were somehow discovered by the authorities. They were punished by suspension from the College.

Under the circumstances both town and college were subjected to an excitement such as Princeton probably never before had felt. The citizens of the town immediately arranged for a patriotic procession, inviting all students who were devoted to the Union to join them. And, on the evening of September 13th, a great crowd of townsmen and students formed a procession on Nassau street, under the escort of the “Governor’s Guard.” Cheering, shouting and singing, the excited mass marched first to the residence of the Hon. Richard S. Field, who willingly answered their call with “an eloquent and patriotic address.” Then, the procession sought the Hon. J. R. Thomson at his beautiful home; but Mr. Thomson failed to meet his visitors. This failure, however, did not discourage the marchers. They sang “The Star Spangled Banner” before the silent house, and then returned to the “Mansion House,” where several ardent speeches were made by students, proclaiming their “love of country” and “hatred of treason.”

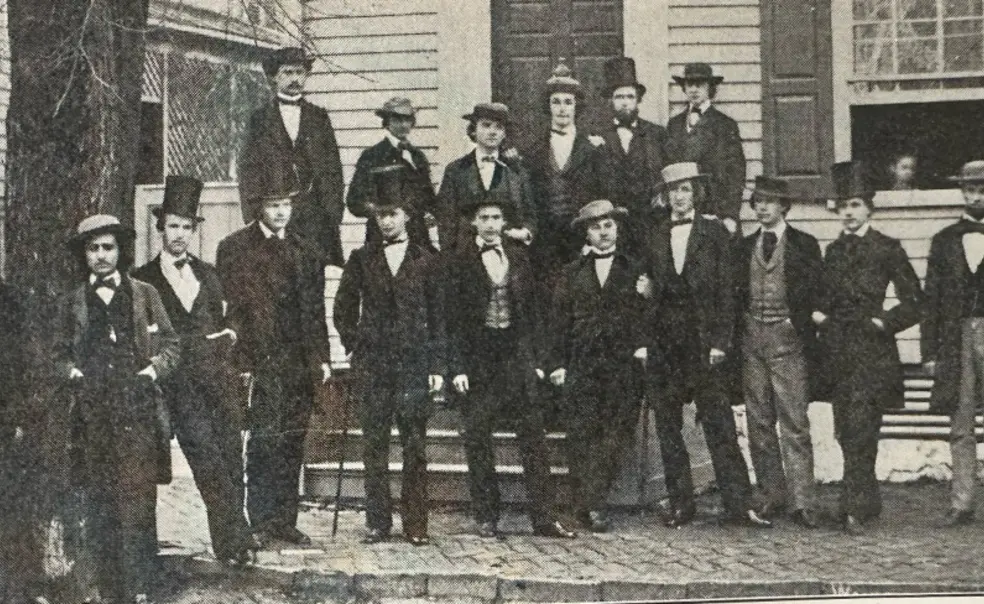

The next day, Saturday, the three suspended students, seated in an open barouche which was heavily draped with the national colors, were drawn by almost the whole body of students “manning the ropes,” in a triumphal procession to the railway station, then at the canal side on the line of the present station branch. No one who saw that shouting crowd of college boys marching slowly to fife and drum music, through Princeton’s main street, cheered on by the waving hands and banners and the “applause of all Princeton,” could ever forget the sight. On that day Princeton College was having a positive realization of its latent loyalty, both among teachers and pupils. At the railway station the departing students made grateful and patriotic addresses to the crowd, urging them all to free Nassau Hall from the slightest taint of disloyalty. In answer, a bold representative of the undergraduates pledged to their departing comrades their gratitude and their own fidelity to the good cause. I will not name the student who was subjected to the humiliation of “the pumping;” but, later in these recollection, I shall have occasion to speak by names of the three who were suspended.

The Passing of a Crisis

Remembering what followed this stirring event, I see that it marked the passing of a crisis in the career of the College. Nothing like it occurred again; the voice of the disloyal agitator was stilled in all our college intercourse; patriotism grew to be more earnest and devoted among us, and the Faculty at last realized fully that they must choose for the College not merely a purposed loyalty to the Union, but a loyalty that would be clearly evident and unquestionable.

The next Monday, September 16, Dr. Maclean, as President of the College, published a long statement about the affair, which was rapidly attracting wide spreading attention over the North. He defended the action of the Faculty, but also he placed the College, beyond question, on the side of the Union. Among other things he said:

“To express their disapproval of this act of violence, the Faculty suspended three of the students known to have been concerned, and directed them to go home; and they have enjoined upon certain other students charged with the utterance of offensive sentiments, that they must in future desist from any utterances which have a tendency to provoke those who approve of the action of the General Government in their efforts to maintain the Union and the Constitution of the country.”

“On the one hand the Faculty will allow of no mobs among the students; and on the other hand they will not permit the utterance of sentiments denunciatory of those who are engaged in efforts to maintain the integrity of the National Government, nor will they allow of any public expression of sympathy with those who are endeavoring to destroy that Government.”

It happened that with this stirring incident I actually began my student life at Princeton, for now, whenever I make a retrospect of the “College during the Civil War,” this “pumping” of a disloyal classmate, with its many associations and consequences, is the fact that fully commands my memory. So strong was the feeling then that a number of the students went about armed. There was talk about secret societies for the suppression of “treason;” and the college guardians were evidently much disturbed over possible serious and even tragic outbursts among the youths in their charge. But, over all, I recollect that after the culminating September excitement Princeton speedily went to the front, among colleges, in a loyal defense of the Union. Her patriotic attitude became all the firmer as the years passed; and, with the passing of the years, by the deeds of her sons in the armies of the Union, proof was made perfectly clear that “Old Nassau” was still, as of old, the Alma Mater of faithful patriots and the nourisher and inspirer of their devotion.

The Nassau Literary Magazine, then beginning to receive its later distinguishing name, “The Lit.,” was celebrating its coming of age when I entered the College. The issue for the notable month of which I have been speaking had an editorial whose opening sentences deserve repeating here:

“We live in stirring times. The tramp of armies and the shock of battle is felt throughout the whole length and breadth of our land. A great people has aroused itself for terrible conflict, to vindicate the Majesty of Law against Treason and Rebellion. This mighty movement is not the result of a mere effervescence of popular feeling. It is the mighty Vox Populi proclaiming for the Union and the Constitution, those twin symbols of our national greatness.”

Taking “The Lit.” as a fair exponent of the mood and strivings of the College as a whole, I find my recollections of the time fully verified. Referring to the September “pumping” and the consequences of the crisis of which it was part, the October editor’s comment was, in brief, — “Much that has been published about it must have ‘perplexed the public’ and given needless anxiety about ‘the orthodoxy of the College,’ but now ‘the whole world knoweth’ and ‘all is in grateful quiet.’”

During that autumn a company of over a hundred, more than a third of our diminished student enrollment, had been gathered for regular military drill, and I read that “our every wish and hope and prayer is that the God of battles will justify us in our appeal to arms.”

Throughout that autumn and the winter of ’61 and ’62, as I recollect, the College was in all relations pervaded by earned and energetic feeling. Not only was patriotic ardor continuously stirred, but expanding and deepening with that was an awakening of religious sensibility. The novel, terrible tragedy of the country’s struggle for existence was accepted by many of these boys as a fact in which they were personally, vitally involved. The ordinary trifling of the play time of the students was markedly lessened in those months. Before the winter had far advanced, the Philadelphian Society’s meetings had become crowded; daily noon prayer sessions were held; many private rooms were the gathering places in the evenings of small groups for Bible readings and other devout exercises. I recollect clearly the Washington’s Birthday celebration of 1862, when the First Church was filled long before the opening hour. In the exercises we were earnestly reminded of patriot duty as a sacred act, and were summoned to our high calling as Americans by readings from Washington’s parting messages to his countrymen. These venerable words seemed, then, to be charged with meanings not understood before.

Student Volunteers

The progress of the great war became far from cheering as the extended daily reports came to us; and many of the boys were impelled to consider seriously their personal duty to the country. Already three, possibly there were four, of my Class, had (1861-62) entered the Union army, — Stanfield, Moffat and Williams. These classmates were to be followed before the calendar year, 1862, closed, with a goodly number more. The profoundly earnest thinking which came from the religious awakening of the winter caused even very young members of the College to wish to serve the country as an act of sacred duty. Insuperable obstacles were put in the ways of several of these earned boys, but quite a number were in the ranks of the army ere long. Many of our southern classmates were already in the service of the Confederacy.

In the early spring of 1862, there came to pass at Princeton an event which is especially valuable as part of this retrospect. Like the September punishment of the disloyal student, this event is of noteworthy significance in connection with the attitude that the College came to have in the Nation’s struggle. A record made at the time of this affair was: “Two years ago a black man lecturing to the learned dignitaries of this place would have been the occasion of effigies and rows; now, it must be marked by the observant world as a step in our college history”… “that such a speaker addressed the collegians and citizens of Princeton,” … “with the eloquent pastor of the church on the speaker’s left, and on his right our worthy, philanthropic President.”

I see now, as though from my seat, close by, in the crowded church, the passing up the aisle, of this negro minister from Liberia, Africa, but graduate of Cambridge University, the Rev. Alexander Crummel, on his way to the pulpit platform, preceded, I think, by Dr. Mann, and followed by our dear old “Johnnie” Maclean. At the time, so I thought, Doctor Maclean showed a good deal of embarrassment under this unprecedented experience for a Princeton College president, but he did his part and said his say bravely. A “Lit.” editorial later made the comment: “So rich an intellectual treat is rarely served us; and had it not to many lost much from the force of prejudice would have beggared the admiration of all.”

Personally, with the close of my first year at Princeton, so I remember, I was engrossed by two emotional impulses; one arising from “the revival of religion” which had affected a very large number of the students of all the classes; the other, a fixed conviction that I must find some way for becoming either a soldier, or some kind of a helper, at the front, among the wounded and the sick. As the year closed we heard that Howard Reeder ’63, son of Governor Reeder of Pennsylvania, had gone into the army and was wounded at Port Royal, S. C. Also, word came the “Ike” Casey of ’64, son of Judge Casey of Pennsylvania, was “in the service.” Both these boys had been suspended as principals in the “pumping” judgment. The third of the trio, “Sam” Huey of Pennsylvania, was allowed to return to College after a while and was graduated in ’63. He also became a soldier soon after graduation, and served the Union honorably. The College year in 1862 closed with the Nation’s integrity more than ever in peril.

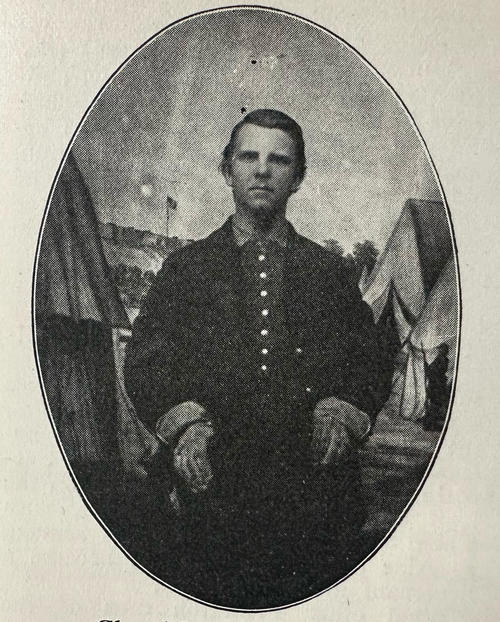

When the next term began, quite a number of our Class and some of the other Classes did not answer at the calling of the rolls. Several had become soldiers. I had succeeded in becoming a member of a Pennsylvania regiment, the 126th, enlisting August 6; soon becoming Ordinance Sergeant of the Second Division, Ninth Army Corps, on the staff of Major General Sturgis, with whom “Ike” Casey of ’63 was serving as Aide de Camp. Later, I became a lieutenant in my regiment.

What other Princeton men of the “Sixties” were in the army of the Union during my connection with the College, I am not able to name fully; I have no access here, in the Far East, to the college records. But I come pretty near the facts, I think, when, with what material I have, I note that, already in September, 1862, my own Class had in active service “at the front” Cox, Hamilton, Holden, Jackson, MacCauley, Marcellus, Moffat, Potter, Howard Reeder, Stanfield, Thomson, Henry M. William, and John M. Williams. From the Class of ’64, Casey and Dilworth had already enlisted; and from ’65, Humphreys and Wood were then absent, “in the field.” But, altogether, taking in the whole course of the war, there were others, making in the end twenty-two members of my Class, ’63, in armed service for the Union. I take from Class Historian Swinnerton’s “Princeton, Sixty-Three,” these additional names: Baird, Breckenridge, Colman, Holmes, Hunt, Huey, MacCoy, Merritt, and Frank Reeder. From the same source I learn that Stryker and Strickler were at the front doing surgical work; that Dewing, Foster, Hoyt and Swinnerton were in service in the Christian Commission, and that Baldwin, Lupton, Nichols and Patton were engaged in departmental work of different kinds. It is also only a just remembrance of “Princeton during the Civil War,” that many of the college men were sincere devotees and good champions of “The Lost Cause.” I can name of these only those of ’63: Gammon, Greenwood, Hueston, Hutchins, Inman, King, Locke, Marks, Phipps, John H. Potter, Reading, Ricks, E. Roach, J. W. Roach, Henley Smith, Washburn and Whaley.

I greatly regret that I cannot make these rolls complete. Probably I speak fully for the Class of ’63. But I wish that a note might follow these “recollections,” showing, as a whole, what Princeton did through all its Classes of the “Sixties” in service both to the Union and for the hapless Confederacy in the South.

College life, as it was passed throughout the next year, 1862-63, I know of almost wholly from correspondence from the army and from a few records I obtained later. I know that the support given to the national cause grew steadily stronger and more useful. Much sympathy was given by both Faculty and present students to those of the College who were in the army and navy. The influence of the great religious awakening of the preceding year was still effective, “strengthening a number of those” who had gone to the war and preparing “those who remained to better fulfil the solemn duties which belong to every Christian in this trying hour.”

Looking through the numbers of “The Lit.” appearing that winter I am reminded that I had been expected to edit the October issue, but, “that ‘the pen is mightier than the sword’ seems not to have been heeded by our friend ‘Mac.’ Doffing his editorial gown, — he suddenly steps into the dignity of the soldier’s life.” I read, also, that the sense of “preparedness” was active, and that “The Nassau Cadets” aroused considerable interest and good natured fun because of their discipline and simulation of the soldiers who were afield. Yet they numbered among them those who later became soldiers in earnest.

The mid-winter emancipation of the slaves of the seceding states aroused much patriotic enthusiasm. I see that “It gives to Abraham Lincoln an heirship of Immortality, placing his name side by side with that of Alexander II of Russia, on the brightest pages of history.” “May God bless Father Abraham, as he did the faithful one of old, for building an altar of his prejudices, policies and fears, and offering thereon his holiest instincts, impulses and convictions for the salvation of his beloved country.”

An Embarrassing “Resurrection”

During the year, “The Lit.” displays an extraordinary interest of the College in the war, as compared with former issues. In the closing number the editor’s pen gives an eloquent eulogy of the progress of civil liberty the world throughout and tells of the “exultant shouts of victory hear din our own land over the recent proclamation of the Chief Executive of the nation, granting Freedom to the whole slave population of the States which are in rebellion. Slavery, thank God, is doomed, whatever be the issues of the struggle in which we are engaged.”

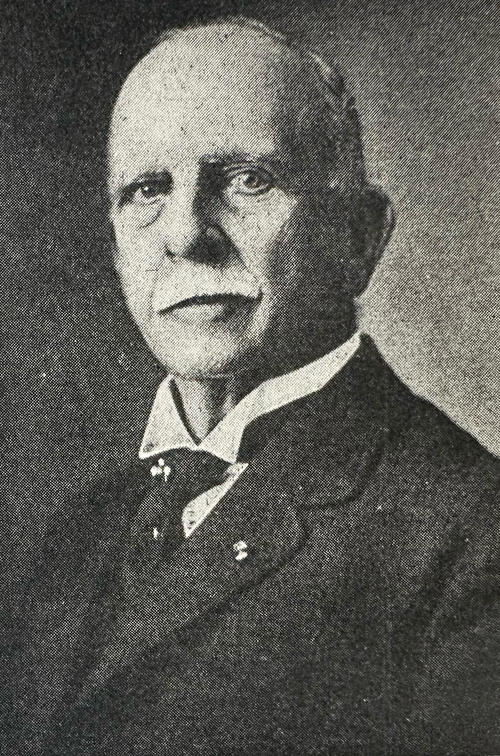

I may be indulged, I assume, in referring to a personal item in this same editorial, — that of the last “Lit.” of ’62-’63. A half page there was devoted to the memory of “Clay McCauley, our classmate, who fell nobly fighting for the cause of Liberty,” “on the last day of the battle at Fredericksburg.” I may not, however, repeat the exuberant revelation then made of my virtues, and of the assurance to friends of my immortality as “Hero and Patriot.” The eulogy was made altogether “premature” by my return for commencement to Princeton, directly from Libby Prison where I had been confined after capture at Chancellorsville — not Fredericksburg. I happened to get to Princeton and to appear on the campus just at the time this very generous “Lit.” was being distributed to its readers. Soon afterwards I met the much harassed editor of the magazine, who exclaimed “I wish to Heaven, MacCauley, you were dead.” My return also damaged the Class Valedictory Oration, much to the orator’s “discomfort,” as he said.

Through the next college year I was again a student, closing my undergraduate career as a member of ’64. The college mood during that year was one of marked contrast with that of the year 1861-62. The intense, strained feeling of the past had disappeared. There had not been any “lapse” in the wide-reaching religious experience of the year past, but there was less fervor and display than formerly. Then, in relation to the war, there was an agreeable relaxation of emotion. Evidently the power of the seceding states was waning, and the preservation of the Union was considered a certainty. We heard of the sick and wounded, and of the dead numbered among our absent college mates, and we cherished them in memory, but the tone of the College had changed. It was well described in a “Lit.” note: “Those of us who remember the last Thanksgiving in the gloomy autumn of ’62, when the proclamation that assigned the day could scarcely enumerate among its blessings the approaching fulfilment of our great hope; when we thanked God for cornfield and vineyard, but could only pray that victory might be granted to our arms, will realize how gloriously that prayer has been answered.” This tone of hope, at times of exultant expectation, continued throughout the year. The repulse of the attempted invasion of the North showed to us that “though an unholy cause may prosper for a time on the soil that nurtured it, yet aggression can never be its policy.” “The great Father of Waters” has “fortress by fortress come under our protection till the whole river is ours.” “What an exhibition of national strength was made” when the rioting in New York threatened “with one fell swoop to destroy all law, order and rights of person and property.” The Government must be upheld and its authority remain supreme.”

I was graduated with the Class of 1864; and with graduation my personal connection with “Princeton during the Civil War” came to a close. But even had I remained with the College until the surrender of the Confederate Army at Appomattox, in 1865, I could not better interpret the tone of the college thought and feeling than was given by one of us at the time of our graduation. “We look forward to the time when peace, an honorable peace, shall again reign throughout the land; when our beloved country, having passed triumphantly through the furnace of Civil War, shall come forth from the conflict purified and refined and free from all impurity when all traces of the curse of slavery shall be swept from the face of the Continent, the foul spot on the pages of American history shall be blotted out; and when we shall be, in fact, the freest people on the face of the earth, honored and feared by all the nations of the world.”

During the following year I was again with the Union Army. I was at the siege at Petersburg in some memorable experiences there; and, at the last, I was again “at the front,” in hospital work in Nashville, Tennessee, when defeat finally befell the Confederacy and peace came to bless the speedily reunited States.

This was originally published in the October 25, 1916 issue of PAW.

No responses yet