Pluralism and the Art of Disagreement

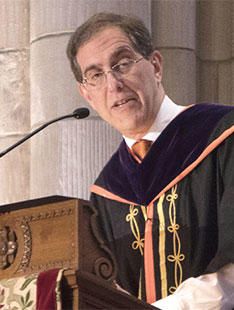

Opening Exercises on September 10 provided an opportunity to reflect on this year’s Pre-read selection, What Is Populism?1 by Professor Jan-Werner Müller. Here is what I told the Class of 2021.— C.L.E.

Today is one of my favorite days of the academic year. It is our New Year’s Day, a day when Princeton starts fresh. We welcome new classes of undergraduates and graduate students, and new colleagues on the faculty and staff. We launch new courses. We look forward to new seasons from athletic teams, publications from writers, exhibitions from artists, and performances from dancers, orchestras, and theater groups— including, this fall, a creative spectacular at the grand opening of our new and beautiful Lewis Center for the Arts.

Yet, if Princeton and many other colleges begin afresh each September, the world around us does not—it hurtles forward at a pace that can seem exhilarating, bewildering, or both. Technology, political parties, international alliances, global climate, transportation, healthcare, how we communicate, how we shop, what jobs we do: everything seems to be changing, and changing very fast.

This year’s Pre-read, Jan-Werner Müller’s What Is Populism?, addresses one aspect of that change: a stunning series of elections around the globe, including Britain’s vote to leave the European Union and America’s election of President Donald Trump. These elections surprised observers and pollsters alike, confounded experts, and cast doubt on longstanding political practices and assumptions. Many people say these elections resulted from “populism.” As Professor Müller points out, people often use the concept of “populism” without defining it carefully, but the term usually evokes the idea that ordinary people are taking power back from some group of elites.

Professor Müller thinks that a different and more troubling trend lies at populism’s core. He argues that populism is antipluralist, and that populist leaders act as though “anyone who does not support them is not properly part of the people.”

If Professor Müller is correct, then populism is at odds with the foundational principles of both the United States and this University. The United States Constitution and Princeton University are pluralist at their core. Both are committed to the idea that people of all races, religions, and ethnicities deserve full and equal respect, and beyond that to the idea that diversity of background, experience, identity, and opinion is, for this country and for this University, one of our greatest strengths.

Professor Müller’s arguments about the relationship between populism and pluralism are directly relevant to the events this summer in Charlottesville, Virginia, where white nationalists marched in support of racism, spewed hatred, courted violence, and injured counter-protestors, killing one of them. The white nationalists’ march was a grotesque affront to principles on which this country is founded, and the killing of the peaceful counter-protester, Heather Heyer, was a crime and a tragedy. What converted the violence from an outrage into a crisis with broader implications, however, was the American president’s equivocating response to it.

Some people have suggested that the University should issue an official statement about Charlottesville, or that I should use this occasion to pass judgment upon President Trump’s comments. The events and the president’s response troubled me profoundly, and it is tempting to share my thoughts with you in detail. It is, however, neither my role nor that of the University to prescribe how you should react to this controversy or others. It is rather my role and the role of the University to encourage you to think deeply about what these events mean for this country and its core values, and to encourage you to find ways to participate constructively in the national dialogue they have generated.

You will find plenty of professors on this campus whose scholarship and erudition will provide you with insight about Charlottesville. As journalists worldwide have sought to illuminate these events and their aftermath, they have turned to professors here, including Eddie Glaude and Keeanga- Yamahtta Taylor in African American studies, Lucia Allais in architecture, David Bell and Kevin Kruse in history, Julian Zelizer in history and public and international affairs, Robert George and Keith Whittington in politics, and Peter Singer in the University Center for Human Values.

I urge you to seek out these and other faculty members, hear what they have to say, and learn from them. Keep in mind, however, that what they offer are not authoritative pronouncements but arguments backed up by reasons. It is your responsibility to assess their views for yourself.

This University, like any great university, encourages, and indeed demands, independence of mind. We expect you to develop the ability to articulate your views clearly and cogently, to contend with and learn from competing viewpoints, and to modify your opinions in light of new knowledge and understanding. Your Princeton education will culminate in a senior thesis that must both present original research and also contend respectfully with counter-arguments to your position.

This emphasis on independent thinking is at the heart of liberal arts education. It is a profoundly valuable form of education, and it can be exhilarating. It can also at times be uncomfortable or upsetting because it requires careful and respectful engagement with views very different from your own. I have already emphasized that we value pluralism at Princeton; we value it partly because of the vigorous disagreements that it generates. You will meet people here who think differently than you do about politics, history, justice, race, religion, and a host of other sensitive topics. To take full advantage of a Princeton education, you must learn and benefit from these disagreements, and to do that you must cultivate and practice the art of constructive disagreement.

Doing so is by no means easy. Some people mistakenly think the art of disagreement is mainly about winning debates or being able to say, “I was right.” It is much harder than that. The art of disagreement is not only about confrontation, but also about learning. It requires that we defend our views, as we do in debate, and, at the same time, consider whether our views might be mistaken.

It requires, too, that we cultivate the human relationships and trust that allow us to bridge differences and learn from one another. That is one reason why I disagree with people who consider inclusivity and free speech to be competing commitments. I believe exactly the opposite, namely, that if we are to have meaningful conversations about difficult topics on university campuses and in this country, we must care passionately both about the inclusivity that enables people to trust and respect one another and about the freedom of speech that encourages the expression of competing ideas.

Building trust depends upon empathy, patience, and sometimes forbearance. The art of disagreement requires a practiced sense of when to listen, calm the waters, remain silent, or simply walk away. Even in a University that thrives on disagreement, you need not rise to every provocation. As you speak with classmates and others, you may sometimes choose to focus on developing relationships, deferring vigorous debate for another day and a more promising moment.

But you also need to find times to speak up, because otherwise you will never have the uncomfortable conversations that really matter. You will never have a chance to test and develop your own views or to inform the views of your peers.

Speaking up is not always easy. As a student on this campus and, indeed, throughout your life—at work, in social settings, and in civic organizations—you will encounter moments when saying what you believe requires you to say something uncomfortable or unpopular. Learning the art of disagreement can help you to choose the moments when it makes sense to speak, and to do so in ways that are effective, constructive, and respectful of the other voices around you. But no matter how good you become at the art of disagreement, you will also need the personal courage to say what you believe—even if it is unpopular.

“Popular” and “populism” share a common Latin root: “popularis”—meaning “of the people.” We are back, in a way, to the question with which we began, about what it means to exercise leadership in circumstances of diversity and disagreement. Some people think leadership depends upon popularity—that it emanates from the approval and praise of a cheering crowd. This University is dedicated to a different view. We are committed to leadership through the rigorous and unstinting pursuit of truth. We believe that sometimes the greatest leadership and the most important insights come not from someone popular, famous, or acclaimed, but from a lone, brave voice insisting on a fundamental principle.

You have been admitted to this University because you have the capacity to become leaders. I hope you will embrace this University’s commitment to leadership through the pursuit of truth and understanding; that you will develop and practice the art of disagreement; and that you will cultivate the courage to speak up even when your opinions seem unpopular.

I hope, too, that you will thrive, grow, and blossom; that you will make friendships that last a lifetime; that you will delight in the joys of learning; and that you will relish these first moments on our beautiful campus. And I hope that you will accept my warmest welcome as you prepare now to march into campus through FitzRandolph Gate as Princeton’s Great Class of 2021.

Welcome to Princeton!

1. Müller, Jan-Werner. What Is Populism? Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016.

3 Responses

Anonymous

8 Years AgoPopulism has of course its...

Populism has of course its good and its bad side. It can be simply a movement to improve the condition of the majority of citizens; it can also be a substitute for real democracy, a way of using authoritarianism and bigotry for nefarious ends while clothed in sheep's clothing. One is reminded of a statement by a German in the late nineteenth century, whose name I have forgotten, that anti-Semitism is the socialism of fools. Populism can be the democracy of fools.

President Eisgruber is of course right on target with his defense of the role of the University and its faculty in providing the material for intelligent decision making. But I would like to remind you that in Germany in the late 19th century and in the period up to the Nazi takeover in 1933 the most illiberal and authoritarian positions were found in the most unlikely of places we might think: the universities, the faculties, and the student body. Much more than business interests, lower-class agitation in the face of economic dislocation, even the outmoded and old-fashioned elites among the military and the old Junker class, the intellectual communities, with some notable exceptions but not too many of them, were foremost in supporting ultra-nationalist, anti-Semitic, geopolitical expansionism, and plain German aggressiveness. It was the elites of Germany, not the people, who brought Hitler to power, and among the elites perhaps the worst group was the sycophantic professors in the universities, universities which were generally considered among the best in the world.

George Coyne ’61

8 Years AgoPluralism, Populism, and Free Speech

Published online Jan. 8, 2018

I read with interest President Eisgruber ’83’s address to the incoming freshman class, which emphasized the importance of open debate and the free exchange of ideas at the University (President’s Page, Oct. 4). Unfortunately, he seemed compelled to first discuss his political opinions and by implication, Princeton’s political opinions, during his Opening Exercises remarks. He started by citing a book by Professor Jan-Werner Müller that suggested that “populism” necessarily leads to “anti-pluralism.” If populism is defined as “ordinary people taking power back from a group of elites,” then certainly the 2016 election provided an example of this. I see no reason why anti-pluralism should result. There is a potent historical example demonstrating that this does not happen. It is the American Revolution, an essentially populist movement, in which power was claimed for individual citizens of the country and taken away from elite groups in England. Princeton’s John Witherspoon was instrumental in inspiring many of the founders and, in particular, mentoring James Madison 1771.

America has been a pluralistic society since its founding, and its power has been based on the power of individuals from every background. “E pluribus unum” is still operative for all those who recognize the genius of the American idea, and want to become Americans. Government remained in the hands of the people and remained limited for nearly 150 years, until the progressive movement was incubated under Princeton’s Woodrow Wilson 1879 and promoted the idea that an intelligentsia should determine what is best for the people. Since then, the federal government has grown substantially in size and power at the expense of individual liberty and control. An unelected bureaucracy and the “political class” have become the modern-day “elite,” and this is what ultimately led to the populist reaction of 2016. I prefer the Princeton of John Witherspoon to that of Woodrow Wilson.

The second political commentary centered on the events in Charlottesville, Va., last summer, and President Trump’s reaction to them. Apparently, condemning violence on both sides was not politically correct. The proper response was to condemn only the white supremacist group, but not the ironically named “Antifa” who arrived armed and initiated the violence, while the local police were conspicuously absent. The message seems to be that if the speech is hateful enough to somebody, violence is permissible.

Needless to say, this attitude leads to a very dangerous slippery slope and a poisonous environment for free speech. Witness Berkeley. For President Eisgruber to explicitly ignore an internal terrorist group such as Antifa in an address to an incoming class in which he chooses to discuss Charlottesville is shockingly irresponsible. Perhaps exposing the danger of internally generated and funded terrorism would be a more important activity than parsing President Trump’s pronouncements.

Norman Ravitch *62

8 Years AgoPopulism is democracy...

Populism is democracy without restraints. It leads inevitably to dictatorship. The people are not able to rule themselves. Democracy works only when people elect elites with knowledge and intelligence. Read Greek history; Athens fell because its aristocratic democracy gave way to populist democracy.