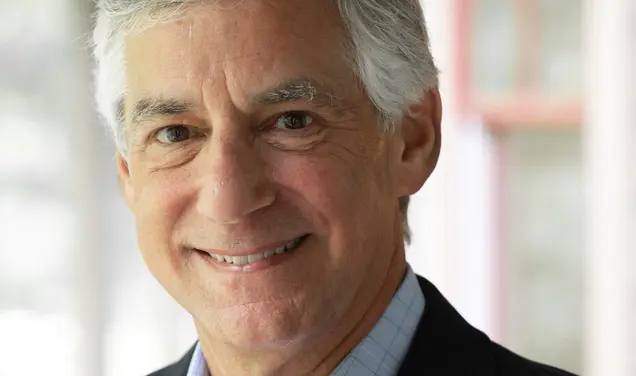

The Political Is Personal: Andrea Campbell’s Story of Change, Grief, and Hope

Andrea Campbell ’04 had been thinking about the words for a long time, but in the end, they just spilled out. On May 25, George Floyd was killed by police in Minneapolis, and on June 3, the Boston City Council met for the first time in two weeks, all 13 members — including Campbell — dialing in to a video chat from their houses across the city, the same thing they’d been doing since mid-March, when COVID-19 closed City Hall for four months. For weeks, they had scrambled to keep pace with the unfolding pandemic and its attendant crises: In meeting after meeting, they called for rent moratoriums, online-accessible food stamps, emergency health-care coverage, and better access to remote learning for low-income students suddenly going to school at home.

But on this afternoon, a new sense of fracture and grief hung over the proceedings. Protestors had been in the streets for days in Boston and in other cities, and some of the demonstrations had turned violent. There were growing calls for sweeping reforms, for defunding police departments altogether, for dismantling various forms of structural racism. The council meeting started with a pastor’s blessing, and he spoke of God’s love and compassion but also of anguish and rage and reckoning. Among their other business, council members filed an order to discuss how to prevent hate crimes and discrimination and offered a resolution condemning police brutality, racial profiling, and “the use of excessive and militarized force.”

“I look at my two boys, and I want them to have more opportunity than I did.”

And then, with about 30 minutes left in the three-hour meeting, Campbell, sitting at home in front of a blue and white curtain, began to speak. “Right now,” she said, “we have an opportunity, not only in this city, but in this country, to start asking tough questions. We are focusing on the wrong ones. We’re focusing on: Why are they so angry? Why are they looting? Why are they yelling at police? Those questions are important, absolutely. But if we are all committed not to be back here again, we have to ask: Why would a man press his knee on another human being’s neck while he cried out for his mother, while he cried out several times for help?”

She paused for a moment. “Folks of color, we know the answer,” she said. “It’s race and racism. It’s at the foundation of this country.” Turning to her white colleagues and constituents, naming them as allies, she asked for empathy and introspection about the pain African Americans were feeling, and a commitment “to do the tough work” of making change. She talked about root causes of injustice and the ways that racial inequality shows up not only in policing, but also in housing, education, health care, the food system, “you name it.” She told them, “We have a chance to do some meaningful things. And, frankly, things that needed to be done a long time ago.”

Lately, the world has been catching up to Andrea Campbell. The day after the meeting, she told reporters she would “absolutely” reallocate $60 million from the Boston Police Department’s overtime budget to community organizations, and she released an action plan calling for a number of changes in the public-safety department, including diversity in hiring, a civilian review board to investigate misconduct, a ban on chokeholds, and an end to military tactics and weapons. “We’ve been doing this work for a long time,” she says 12 days after the council meeting, when asked about the catalyst of Floyd’s death. “What’s different is that the folks who are leading the system — white folks, white men — are now starting to hear it and understand.”

Campbell arrived in City Hall in January 2016 after unseating a 32-year incumbent. Two years later, she was voted council president, becoming the first African American woman to serve in that role. More than once, her name has been floated for mayor. She represents the city’s fourth district, an area taken up primarily by the neighborhoods of Dorchester and Mattapan, which began shifting in the 1960s from white working class to mostly African American and Caribbean. During the city’s school-desegregation busing crisis in the 1970s, Dorchester and Mattapan, two of the neighborhoods affected most, became flashpoints for violence. Today both are racially diverse and relatively high in poverty. They are also heavily policed.

From the beginning, Campbell had criminal-justice reform on her agenda. In part, that has to do with her family. At that early-June city council meeting, Campbell’s voice shook when she spoke about her sons, then-2-year-old Alexander and 5-month-old Aiden. “Both Black boys,” she emphasized, whose skin color, she knows, puts them in greater danger, because some people perceive them as threatening. “I look at my boys, and I want them to have more opportunity than I did,” she said, “and for other folks to value their lives just as much as I do.”

Campbell’s personal story is also her political story; surviving the one propelled her into the other. Her story has chapters of great loss: of two parents, of two brothers — a twin who died while in police custody, a big brother charged with a serious crime. A loss of family dreams.

She was raised in Roxbury, often called the heart of Boston’s Black community, and the South End, a racially diverse but economically stratified neighborhood where Victorian rowhouses stand alongside public-housing projects. Campbell was 8 months old when her mother was killed in a car accident while traveling to visit Campbell’s father in prison. He ended up serving eight years on firearms charges, and so Campbell and her brothers — her twin, Andre, and older sibling, Alvin — spent their early childhood with a collection of foster parents and extended family, including a grandmother who struggled with alcoholism and an aunt and uncle who became parental figures for Campbell. When her father came home from prison, she and her brothers went to live with him.

Andre’s death transformed Campbell. Throughout her tumultuous childhood, he had been her closest companion, her other half.

He was often angry — at what he’d been through, at what he’d lost, at the racial prejudice he believed had robbed him of a better life. “My father was extremely intelligent,” Campbell says. As a high-school senior, he told her, he was accepted to Princeton — and would have been among the first Black undergraduates there, coming to campus in 1951. But he didn’t enroll. Campbell remembers him deflecting questions about it later in life: “‘What am I going to do down there with all those white people?’ That’s literally what he would say.” She recently learned that there was more to the story: When he was 17, her father was arrested for the first time. And although several friends and relatives showed up at the hearing as character witnesses and to plead for leniency, the judge said no. “I think that sort of cemented where my father was going,” Campbell says.

He tried to push his children in a different direction. “He was really good at not just talking about inequities in theory,” Campbell says, “but sharing the lived experiences. Even when we were really young, he didn’t shy away from showing that frustration.” Being born and raised in Boston, a city he loved, was a source of enormous pride, she says — and yet: “A Black man growing up here, born in 1933 — how hard that must have been. At that time, the color of your skin was always made explicit. Not sometimes — always.” Campbell was 19 and at Princeton when her father died, from a sudden illness. “I talked to him that morning, and he literally passed that evening,” she says. “It shook my world.”

School was a refuge. It had been that way since she was a child. Education was part of what saved her, Campbell believes. The “product of busing,” she attended five public schools in Boston, and at first, she and Andre were kept together. But as they grew older, they were assigned to different classes — “because we’re twins and we should find our own identity.” Then Campbell caught what she describes as almost a lucky break: A teacher noticed her and the school put her in an advanced class. “And suddenly, I’m on a trajectory that would bring me to Boston Latin School,” an elite public school, the oldest in the country, with competitive admissions. “And without Boston Latin School, I don’t get to Princeton University. That’s how my path is laid out.”

“What she went through, you know, that was eye-opening to me,” says Michael Contompasis, a former superintendent of Boston Public Schools who was Campbell’s high school principal. “Just the grit and determination. And the work. She always put in the work.”

“Growing up the way she did absolutely proved her fortitude,” says attorney Brent Henry ’69, a former Princeton trustee. A few years ago, he and Campbell were introduced by a mutual acquaintance and became friends. “She has a story that a lot of politicians talk about but don’t live,” Henry says.

Thinking back now on why Andre wasn’t tracked into advanced classes too, she believes partly it was gender-based: “Andre was acting out, and probably because of things happening in our home, but, you know, we both acted out.” Campbell recalls being sent to the principal’s office or told to sit at the back of the classroom. Andre, by contrast, was more often suspended or expelled. While her brother was attending schools with fewer resources and weaker academics, Campbell says, “I’m in schools where you can get job opportunities, where there’s programming that was free for us girls.” As a Girl Scout, she went camping in New Hampshire. Sports programs allowed her to visit colleges out of state. “I was just exposed to a world that Andre didn’t have.”

Campbell arrived at Princeton as a prospective math major. “I had a wonderful experience,” she says. “I was kind of a nerd, and I put my head down to do the work.” But when her father died during her sophomore year, something shifted. She began studying sociology instead — looking for answers, maybe, about the place she’d come from — and, somewhat unexpectedly, Judaic studies. She had taken a course on American Jewish history, drawn to it partly by the stories her father had told about growing up in neighborhoods that had once been Jewish. “And then I just kept taking Judaic studies classes,” she says. “Often I was not only the only woman and Black woman in the class, but also the only Christian.” She wrote her junior paper and senior thesis on Black and Jewish relations in urban settings and worked at the Center for Jewish Life.

After Princeton, Campbell went to law school at UCLA and then returned to the East Coast, working first at a Roxbury nonprofit specializing in education law and offering free legal services and later in New York. In 2012 she returned to Boston for good, to be with her boyfriend — now husband — Matthew Scheier, and to be closer to Andre, who needed her. “But in the midst of my returning, he passed away.”

Andre’s death transformed Campbell. Throughout her tumultuous childhood, he had been her closest companion, her other half. What was he like? Her face brightens. “Andre was smarter than me — I always tell people that,” she says. “He was hilarious, always joking, laughing. And very compassionate and empathetic. He was a feeler, even as a kid. If someone’s suffering, he was like, ‘Let me make my way over there.’” Even when Andre started having his own troubles, cycling in and out of prison, she says, “he always found time to call a loved one who was sick.”

He was a pretrial detainee when he died, at 29. The details of what happened are still not clear to Campbell. Andre had been behind bars for two years, awaiting trial. He had an autoimmune illness called scleroderma that can affect the skin, blood vessels, muscles, and other organs; before his arrest, Campbell says, the condition was being treated and under control. But during those two years, different lawyers came and went, and court dates were changed, “and all the while, he was deteriorating,” she says. “He had a high cash bail that I could not afford to pay. So, he was sort of in the system, in and out of hospital settings, not receiving adequate treatment.” He developed sores on his feet, he lost weight, he was often in pain; at one point he went into cardiac arrest. When prison officials called to tell her, Campbell went to his bedside, and with two armed guards in the room, she held his hand and prayed with him. “I said, ‘It’s not your time yet.’” But a year later, Andre died.

Going through his personal items afterward, Campbell came across a grievance form he’d filled out, asking for medical care. “Clearly, from his description, you can tell he was in distress and in need of help immediately,” she says. But the form had been returned to him with instructions to fill out a different document instead. “This was the response,” she says. “It was almost like he was guilty and being mistreated even before the legal system found him guilty.”

She was a Princeton graduate, a lawyer, a woman with skills and connections — and yet, she had been unable to help her brother. “I sat in a space of anger,” she recalled in a podcast. She prayed. After the fog of grief began to clear, Campbell found herself with a question that continues to fuel her work: “How do twins born and raised in the same city have such different life outcomes?” Even all these years later, the gulf between her own life and Andre’s startles her. “That’s my purpose now,” she says: finding ways to close the gap.

Andre’s death would not be the final tragedy in Campbell’s family. Early this year, her older brother, Alvin, was arrested and charged with raping a woman after posing as a rideshare driver — and in July he was charged with sexual assault against seven other women as well. If convicted, he could be sentenced to life in prison. He has pleaded not guilty. “It’s been truly painful, to say the least, and shocking and disheartening,” Campbell said after the initial charges. “I have gone deep in prayer — for the victim and my brother — to respond. But, frankly, it has expanded my purpose, to do the work of interrupting cycles.”

She no longer blames individual people for injustices, she has said — instead, she looks at systems and the inequities found in them. The education system. The criminal-justice system. Campbell knows the world of Princeton — its groomed grounds and historic halls and its network of friends and strangers willing to help a young person deemed smart and special. And she knows the world in which her brothers lived, as well, where detainees are viewed as “almost not human.” They’re sons and daughters, too.

It’s no surprise, then, that Campbell has spent much of her career thinking about how to break the cycles that have trapped so many: “cycles of criminalization, cycles of poverty, cycles of trauma, cycles of abuse, cycles of mediocrity — all these cycles that show up in my family and community, and in every community, frankly, not just communities of color.”

In her first year on the city council, she visited every school in her district. What she saw again and again, she says, were teachers and school administrators who felt powerless to deliver the resources — rigorous instruction, good facilities, educational supports, extracurricular opportunities — that their students needed. They weren’t always sure of what help they could count on from city officials. In 2019 Campbell released a 16-page plan designed to give local schools more control over curriculum and programming and to hold the central office accountable for student outcomes. She has also pushed to make selective-admissions public schools, like Boston Latin, more equitable and diverse. “The whole thing for me is, what are people’s needs, and how do we strengthen public institutions to meet those needs?” she says. “Right now, Boston Public Schools are not serving the needs of students of color, or poor families, or special-needs students, or English-language learners. And when public institutions are not serving people’s needs, where do they go?”

“I don’t want [my sons] to live in fear, or to have to change how they show up in the world or be inauthentic because folks think they are threatening or lesser-than.”

Her plan for public-safety reform is also focused around people’s needs, she says, and imagines a police force not abolished, but scaled back: more service requests — and more money — directed toward community-based organizations, and more accountability for citizen complaints against law enforcement. The civilian review board she proposes to investigate misconduct would be independent of the police department, have the power to issue subpoenas, and regularly publish data about complaints, stops, arrests, and use of force. Police would be removed from schools, and tear gas and rubber bullets would be among the military weapons banned.

“I think it is critically important, the fact we’re talking about police-brutality cases,” she says, “but it is also absolutely essential that we recognize that race and racism play a role in every system in this country — marginalizing, oppressing, or even killing residents. It’s important that we have plans in place in education, health care, banking ... all the other systems that no one’s really talking about.”

It’s part of a larger lesson she’s learning about politics, and community, and the potential for breaking cycles. “What I’ve come to know is that the political arena touches everything. I don’t think that our residents always understand that. ... I’ve been telling them that’s why this political game matters so much. It touches every piece of their life.”

And every piece of hers, too. When Campbell talks about the neighborhoods she represents and her aspirations for the people living there, the conversation often winds back to her two sons and their futures. It is a fraught time to be the mother of Black boys. She explains how she hopes her sons would have a “different experience growing up in America. I don’t want them to live in fear, or to have to change how they show up in the world or be inauthentic because folks think they are threatening or lesser-than.”

In an essay published not long after George Floyd’s killing, Campbell wrote of forcing herself “to feel every emotion that surfaces”: anger, frustration, fear, “debilitating sadness.”

And hope, she adds later: “I don’t have the luxury of not forging ahead.”

Lydialyle Gibson is a Boston-based freelancer and associate editor of Harvard Magazine.

2 Responses

Stephen Jackson ’60

5 Years AgoBeyond Inspirational

The article “The Political is Personal: Andrea Campbell’s Story of Change, Grief, and Hope” (September issue) deserves high praise. Her deeply personal and courageous journey immersed in systemic racism is beyond inspirational as she pursues a societal commitment “to do the tough work” of making comprehensive and meaningful changes. After all, it is deed, not simply creed, that offers hope for all of us. Andrea makes me so proud of being a Princetonian.

Editor’s note: Two weeks after PAW’s story was published, Andrea Campbell ’04 announced she would run for mayor of Boston in 2021.

John W. Unger Jr. ’74

5 Years AgoHope for the Future

Reading about Andrea Campbell gives me hope for the future. What a remarkable person. The Q&A with Scott Berg provided excellent perspective on Woodrow Wilson. I encourage everyone to read the expanded interview online. Another great issue!