Power to the People

Social psychologist Amy Cuddy *05 explains how we make judgments, and how our bodies can help us feel more powerful

When Amy Cuddy *05 walked into her classroom at Harvard Business School a few years ago to teach about power and influence, she found herself watching the body language of her students. Some of them — mostly men — were going straight to the middle of the room before class, leaning back, and generally occupying a lot of space. Others, mainly women, seemed to make themselves small — they hunched over, wrapped their arms around their bodies, and crossed their legs. These students also tended to participate less in class discussions and seemed less confident. When raising their hands, men were more likely to thrust them high in the air, while women seemed more tentative.

Studying the postures of the women, Cuddy, who is a social psychologist, wondered: “If I could change the way they sat, would that make them feel more powerful?” Cuddy took her hunch to the lab. With Dana Carney, a professor at the University of California, Berkeley, and postdoctoral associate Andy Yap, she came up with a study to examine how your body language affects not how others perceive you, but how you perceive yourself. Their hypothesis was that pretending to be powerful, by striking a power pose, would make people feel more powerful — and, as a result, make them act more powerful.

In the study, participants were asked to hold a “high-power pose” — for example, with feet propped up on a desk and hands clasped behind the head, or standing and leaning over a desk with arms outstretched for support — or a lower-power pose, hunched over with limbs tucked together. The high-power poses were drawn from research on nonverbal expressions of power and dominance in the animal kingdom: Powerful animals make themselves big and stretch out. After the participants in Cuddy’s study spent two minutes in the poses, saliva samples were taken, and each person was given $2 and offered the chance to roll a die to double his or her money.

Of those who adopted high-power poses, 86 percent elected to gamble, versus 60 percent of those in low-power poses. High-power posers experienced a 19 percent increase in testosterone versus a 10 percent drop for low-power posers. Cortisol, the primary hormone released in response to stress, went up for low-power posers and down for high-power posers. (Both men and women participated.)

Then the researchers followed up with a second experiment: After participants assumed the poses, they were given a stressful five-minute job interview. Trained evaluators who had no idea of the study’s hypothesis — and had not seen the participants posing — graded the interviews, and gave higher marks to the performances of those who had adopted high-power poses.

Cuddy’s conclusion? Yes, powerful body language can boost confidence.

“Our bodies change our minds, and our minds can change our behavior, and our behavior can change our outcomes,” she says. Now Cuddy advises her students — and others — that before entering a stressful situation, they should slip into a private space and spend two minutes in a power pose, such as standing up straight with feet apart and hands on hips, Wonder Woman style.

Teaching at a top business school made it “inevitable that I would become interested in power dynamics,” Cuddy explained in a TED talk about power poses that she gave in 2012. As of December, the lecture was the fifth-most-viewed TED talk of all time, seen more than 15 million times and translated into 37 languages. People all over the world — from athletes to politicians — have emailed her to say they are using her technique. (To view a Time magazine video of Cuddy discussing the poses, go to paw.princeton.edu.)

While it’s the power pose that has brought Cuddy public acclaim, in academia she is equally known for her influential work on stereotyping and the role our judgments play in societal interactions — much of that work done with Princeton psychology and public affairs professor Susan Fiske, Cuddy’s former adviser, who is highly regarded for her research on how people think about other people, including prejudice and discrimination. Their work has helped shed light on the factors that contribute to determining which job candidates are hired for different kinds of jobs, and which groups are targeted for different kinds of persecution.

In her office at Harvard’s Baker Library, with its white-columned entrance and wood-paneled faculty dining room, Cuddy, a former ballet dancer, projects an image of confidence mixed with femininity. Petite and well-dressed, with shoulder-length flaxen hair accented by a shimmery pink pearl necklace, she is soft-spoken but self-assured.

Cuddy was a free-spirited sophomore studying theater and American history at the University of Colorado when an accident in 1992 changed her path. Returning with college friends from a visit to Montana, she was asleep in the back seat of a Jeep Cherokee when the driver nodded off and the car veered off the road and rolled over three times. Cuddy was thrown out a side window and suffered a traumatic brain injury. During a years-long recovery, she was told her IQ had dropped 30 points. Doctors told her she was “high-functioning” but that there was a good chance she would not finish college.

Cuddy’s injury left her struggling with reading and processing information. “It was very hard for me to sit in a lecture,” she says. “I would take copious notes and still couldn’t make sense of what I was hearing.” She tried several times to go back to school, but had to drop out. “I did believe working hard would help stimulate some neurologic recovery — that it would help my brain heal. I don’t know if it did or it didn’t, but I did everything I could.” Eventually she completed college, earning her degree six years after the accident.

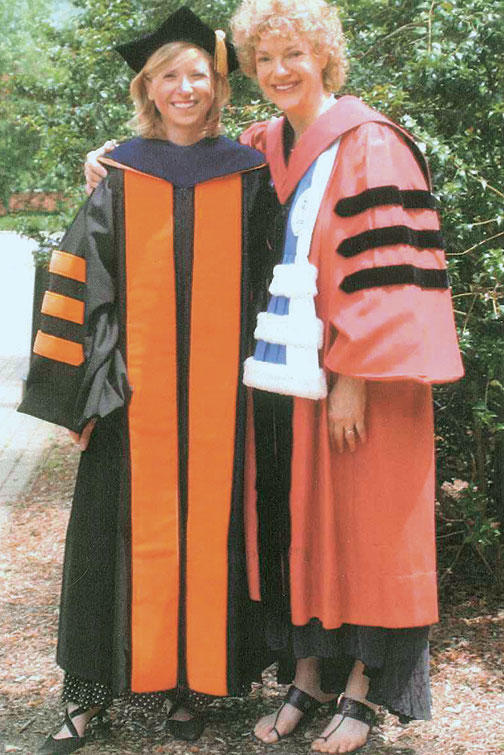

Her brain injury inspired Cuddy to start studying neuroscience; she later switched to social psychology, which appealed to her lifelong interest in social justice. After graduation, she took a position as a research assistant with Fiske at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. The position was unpaid. “I was willing to do anything,” says Cuddy, who still felt she was lagging behind. “My first statistical analysis I did by hand, just to show her that I understood it conceptually. I brought in pages and pages of handwritten notes.” When Fiske joined Princeton’s faculty in 2000, she brought Cuddy along as a Ph.D. student.

Cuddy found Princeton “completely intimidating”; she felt she had to work harder than her peers because of her brain injury and her lack of a “fancy pedigree,” she says. Married the day she had graduated from college (she later divorced), she had a son during her second year on campus. Fellow students thought she had “a confidence that was not intimidating” and sought her help with academic problems and other dilemmas, recalls Crystal Hall *08, now a professor at the University of Washington. But Cuddy did not see herself that way.

It was Fiske who showed her that it was possible to “fake it ’til you make it” — a sentiment that undergirds her research on power poses. In her TED lecture, she described the night before an important talk she had to give as a first-year graduate student, when, feeling like “an imposter,” she called Fiske and said, “I’m quitting.” Fiske replied: “You are not quitting, because I took a gamble on you, and you’re staying. You’re going to stay, and this is what you’re going to do. You are going to fake it.” Eventually, Fiske told her, she would “have this moment where you say, ‘Oh my gosh, I’m doing it. Like, I have become this. I am actually doing this.’” And, Cuddy explains, that’s what eventually happened to her. She takes Fiske’s advice a bit further, concluding: “Don’t fake it ’til you make it. Fake it ’til you become it.”

When Cuddy was still in graduate school, the pair, led by Fiske, began working on what would become a signature achievement: a new way of looking at stereotyping and prejudice. Traditionally, prejudice was viewed through a one-dimensional lens: In-groups are loved, out-groups are reviled. Fiske and Cuddy, along with Peter Glick of Lawrence University in Wisconsin, found that people form judgments of others in a more nuanced way, based on two initial factors — warmth and competence — and the conclusions people draw are multilayered. “It’s a simple model that was grounded in a vast amount of literature in social cognition,” Cuddy says. “It’s broadly applicable to so many situations that involve social perception.” Their 2002 academic paper laying out the warmth/competence theory quickly became a classic, and has been cited by other researchers more than 1,500 times.

Other studies by Fiske and Cuddy helped illuminate the subtleties of attitudes toward the elderly, for example: Older people are regarded as warm but incompetent, leading people to have positive feelings toward them while failing to respect them, which may result in discrimination in the workplace. “People are much more likely to help these people across the street, but they’re also more likely to neglect them, and those behaviors are correlated,” Cuddy says. The thinking, she points out, is, “I’ll help them because they’re sweet and harmless, but I’m not going to involve them in a professional setting.” Other groups that fall into this liked-but-disrespected category, Cuddy says, are disabled people and stay-at-home mothers. Few groups garner reactions that are wholly positive or negative. “Most groups are either liked or respected, but not both,” Cuddy says. These attitudes result in “what you see on a day-to-day basis: more subtle discrimination.”

Cuddy and Fiske’s work “has decidedly advanced our thinking about stereotyping,” says Madeline Heilman, a psychology professor at New York University who studies gender stereotypes. “It is an incredibly useful framework for identifying similarities and differences in how different groups are viewed and the reactions they are likely to elicit. Because of its simplicity and clarity, the model has become a major way of thinking about stereotyping and an important means of both understanding when discrimination is likely to occur and what form it is likely to take.”

To examine how women in the workforce are perceived, Cuddy, Fiske, and Glick ran a study in which participants were asked to evaluate fictitious profiles of McKinsey & Company consultants and decide whom they wanted to hire. The fictitious candidates had the same professional qualifications but different personal profiles: childless women, childless men, women with children, and men with children.

The study found that working mothers were the least likely to be hired or promoted — they were perceived as warmer than men, but also less competent. “People say, ‘I like working moms. That’s not prejudice, right?’” Cuddy says. “Well, it is, because these same people don’t see them as competent, they don’t respect them, and they don’t hire them.” Fathers in the study benefited from having children — they were seen as warmer than childless men while maintaining their perceived competence. Women, Cuddy says, are just as likely to hold these prejudices as men.

In general, Cuddy and her colleagues have found, people tend to see warmth and competence as inversely related. The perception, explains Cuddy, is, “She’s so sweet. ... She’d probably be inept in the boardroom.” Groups prejudged as high in both warmth and competence — such as the middle class — tend to be admired by other groups, while those seen as neither warm nor competent — poor and homeless people, for example — often are socially excluded. The wealthy tend to be seen as competent but not warm.

Today, Cuddy teaches her Harvard students that when people evaluate leaders, warmth is weighted more heavily than competence. “The trust piece has got to come first, and people make the mistake in professional settings of thinking they need to put strength and competence before warmth,” she says. “If you don’t establish trust, you have no conduit of influence.”

Cuddy has explored other preconceptions as well: One of her studies, for example, found a race-based double standard in how working mothers are judged. Participants were asked how much money several hypothetical families should spend on a Mother’s Day gift — the only variables were the race of the mother and whether she worked outside the home. White stay-at-home mothers received a higher-cost gift than white working mothers, but for black women, the reverse was true: Black mothers who worked received the higher-cost gift. The study demonstrated that society has an “expectation that black and Latina mothers should be in the workforce,” and white mothers should be home with their children, Cuddy says: “There was something punitive” about how the fictional mothers were treated.

While Cuddy’s work on stereotyping may help us better understand our interactions with others, power posing may help us improve them.

“What I think is so beautiful about this is that it’s free, and almost anyone can do it, regardless of their formal or informal power, or their resources,” Cuddy says. Power posing is not about having power over another person, she says; rather, it helps you operate at your best. As she explains in her TED talk, “Don’t leave that situation feeling like, ‘Oh, I didn’t show them who I am.’ Leave that situation feeling like, ‘Oh, I really feel like I got to say who I am and show who I am.’”

Outside of her classes at Harvard, where Cuddy arrived in 2008 after teaching at Rutgers and Northwestern, she gives speeches about her work to groups ranging from management consultants at Accenture to Canadian trial lawyers to editors at Cosmopolitan. She uses catchy images and clear language, shares her bright smile, and has a strong stage presence, a legacy of her ballet training. She also doesn’t take herself too seriously, ending one presentation by playing the Wonder Woman theme song and, during another, clasping a pencil between her teeth to demonstrate that forcing yourself to smile can elevate your mood. “She has a sense of style about how she presents ideas,” says her mentor, Fiske. Her talks “are straight to the point and aesthetically appealing.” She also is working on a book about how people can “nudge” themselves psychologically to improve their confidence, performance, and general well-being.

Cuddy says she has received about 10,000 emails from people living all over the world who use power poses. Among them: people recovering from brain injuries, professional athletes, adults and children in an anti-bullying group, horse trainers, and performing artists. One man wrote to tell her that his boss, a member of Congress, calls the power poses “doing his Supermans.” Harvard’s assistant volleyball coach, Jeffrey Aucoin, plans to use power posing to help his players “come out onto the court and act like they own the place.”

For Sarita Gupta, who often gives speeches on workers’ rights as executive director of Jobs With Justice, power poses “help me feel I’m in control of the moment. As a woman of color and a younger woman, how do I show up with authority?” Before addressing a crowd of thousands at a convention recently, she ducked behind a black screen that was onstage to “get big,” as she calls it. “I don’t care if I look really ridiculous. It reminds me I want to be powerful.”

Cuddy’s findings have spawned spinoff research: Two professors have found that people who adopted a power pose displayed higher pain thresholds. The study “suggests that power posing may be a useful tool for pain management. Even individuals who do not perceive themselves as having control over their circumstances may benefit from behaving as if they do by adopting power poses,” the researchers wrote. Cuddy, meanwhile, is studying the outcomes of negotiations when power posing is done beforehand, and whether the poses can improve physical coordination. She and a colleague are examining whether power posing affects financial decision-making by poor people in Kenya. And she is working with computer scientists to develop a game that incorporates power posing with the aim of reducing children’s math anxiety.

The ease of doing power poses — and the accessibility of Cuddy’s TED talk explaining them — has enabled her work to spread far beyond her Harvard lab, which makes her very happy. “What matters the most to me is sharing the science,” Cuddy says. She likes using that science to “find small tweaks to improve our own outcomes and well-being,” she says. “I like figuring out how we can help ourselves be better.”

Jennifer Altmann is an associate editor at PAW.

3 Responses

Ron Gerber ’82

9 Years AgoA Pose For Power

I hope that PAW received a product-placement fee from Professor Amy Cuddy and a share of future consulting revenues from the blatantly self-promotional cover story. There should have been a disclaimer at the top of each page, saying “Paid Advertisement.” I support coverage of non-traditional topics like body-language research, but the decision by PAW to give a Harvard professor such prominence, together with the content of the article, is inappropriate and offensive for two main reasons:

1. Aren’t there enough Princeton professors whose research qualifies them for cover-story material? This article should be a few paragraphs at most, not five full pages. PAW should give priority toward articles that keep alumni informed about the University.

2. I emphasize to my children, players that I coach, and employees that you achieve success through “hard work and perseverance.” Professor Cuddy says, “Don’t fake it ’til you make it. Fake it ’til you become it.” This may be different sides of the same coin, but they have a very different and profound impact on the listener. People hear “hard work” when I speak, while they remember “fake it” from hers. In an era of reality television, this sounds better but seems at odds with the culture (integrity, character, honor code) that alumni want at Princeton. PAW’s decision to give her cover-page exposure is unfortunately a de facto endorsement of this philosophy. Remember that dozens of Harvard students recently were required to temporarily withdraw for cheating or “faking it.”

PAW, like any other print publication, is struggling in today’s digital world. But publishing an article better suited for People, if not the National Enquirer, is not the answer.

Ann Gordon Bain s’53

9 Years AgoA Pose For Power

The Amy Cuddy *05 article reminded me of my childhood, changing schools 15 times and always being a misfit. I saw the movie The King and I, in which Anna and her son are standing on the deck of a ship arriving in Thailand and the boy is afraid. She sings with him, “I whistle a happy tune, and no one ever knows I’m afraid.”

I started doing this quietly to myself under stressful situations, and it worked. I am now 76 years old and a tennis pro. People ask me how I can be so confident, and I reply, “I whistle a happy tune, and no one knows I’m afraid.” As Cuddy said, I am no longer afraid — I have changed by “faking it.”

Leontine Galante *07

9 Years AgoA Pose For Power

Re “Power to the People” (cover story, April 2): Fascinating research — and such an innovative series of readouts. Many people assume that because we have graduated with a Ph.D. from Princeton, we are not only completely confident, but maybe even arrogant. But these things are more internal. However, it is so empowering to see a simple way to “fake it” and to physically/psychologically “make it.”