Preparing for a new era of partnerships overseas

Four years after issuing a blueprint for “a broad international vision” for Princeton, the University is preparing to create strategic partnerships with educational institutions in other countries.

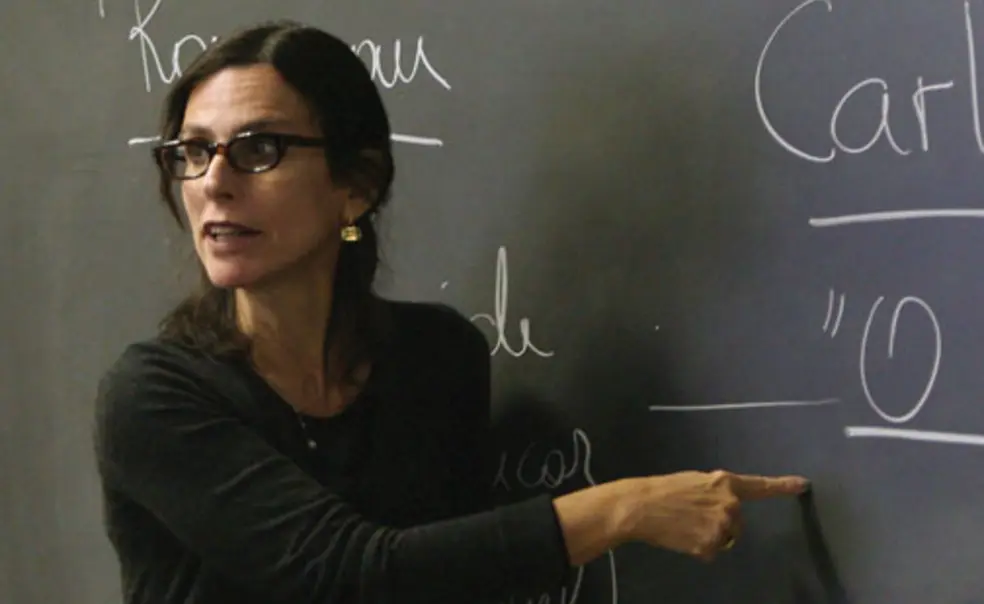

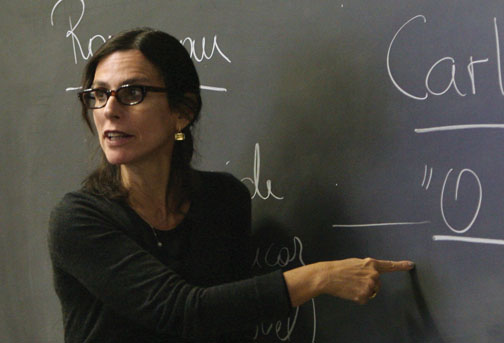

Partner institutions are likely to be selected from those that already have been “hot spots” of activity for Princeton faculty and students, according to history professor Jeremy Adelman, director of the University’s Council for International Teaching and Research.

Among the early candidates are the University of Tokyo and the University of São Paulo in Brazil, Adelman said. Partnerships in China, Western Europe, and Africa — perhaps with multiple institutions or locations — also are under consideration, he said.

In October 2007, President Tilghman and Provost Christopher Eisgruber ’83 issued a report called “Princeton in the World” that made the case for globalization and outlined a series of initiatives, including one of faculty-driven “networks and flows” that would connect the University to centers of learning in other countries.

That has led to formal connections among faculty, grad students, and undergraduates in more than 25 locations overseas, Adelman said. But to sustain those networks, he said, more institutional support and a deeper commitment are needed.

The 2007 approach “did not do anything transformative to the institutions — they remain separate entities,” said Diana Davies, vice provost for international initiatives. The new strategy will rely on institutional relationships, with oversight by a governing body comprised of faculty from both institutions that will determine new programs, activities, and collaborations.

The strategic partners would offer courses, seminars and conferences, and research exchanges for faculty and students. The University plans to provide assistance to visiting faculty and students in areas such as housing and arrangements for research staff and facilities. “A strategic-partner campus should become a home away from home for Princeton students, faculty, and staff,” Davies said.

Princeton hopes to create about six partnerships within two years, she said, and the University of Tokyo has emerged as a leading candidate. The East Asian studies department has strong connections, Woodrow Wilson School faculty members share security studies with Tokyo, and astrophysics faculty and students regularly travel back and forth, she said.

Davies said Princeton and Tokyo are “well under way” to developing a partnership agreement. Immediate goals are to encourage more faculty and student mobility, expand undergraduate involvement, and spell out a governance structure.

Princeton also has been working toward an agreement with the University of São Paulo, Brazil’s largest institution of higher education, Adelman said. He cited ties to São Paulo by Princeton’s Program in Latin American studies and the departments of astrophysics, Spanish and Portuguese languages and cultures, and sociology.

Partnerships in other regions also would build on established connections, but the details could look quite different. In sub-Sahara Africa, a major challenge is the gap between a small number of institutions with significant resources and others struggling to get by. In Europe, Princeton has a high level of activity with a number of institutions in France and Germany; Adelman said one solution might be to position the University to work with a number of institutions in a “spoke-and-wheel” type of arrangement.

In China, University departments have collaborated with their counterparts at several institutions in Shanghai and Beijing, Davies said. She said Princeton hopes to develop a partnership that would support relationships “with all these top universities.”

While New York University-Abu Dhabi opened in the fall of 2010 and Yale is partnering with the National University of Singapore to create a new liberal-arts residential college, plans by universities for branch campuses in other countries have slowed recently.

“The shine has rubbed off” the branch-campus option, Adelman said, noting that Princeton continues to oppose the idea of a bricks-and-mortar campus abroad. “It’s easier to build an extension of yourself,” he said, but the partnerships that are planned would “internationalize us in a very different way — by including others into our activities and commitments at home.”

A different type of international collaboration is a planned dual-degree program with Humboldt University in Berlin — Princeton’s first dual graduate degree in the humanities, initially in German and philosophy. Students would do most pre-dissertation work at their home institution, but would have dissertation advisers and would spend time at each university. A completed agreement is expected this spring.

Five years from now, Adelman said, Princeton will be “a very networked university, with key partners around the world, full of global classrooms in which you’ll hear multiple languages.” With a wide range of international programs to select from, he said, “students won’t have to choose between being at Princeton and out in the world.”

No responses yet