Princeton Advances on Path to Net-Zero, But Challenges Remain

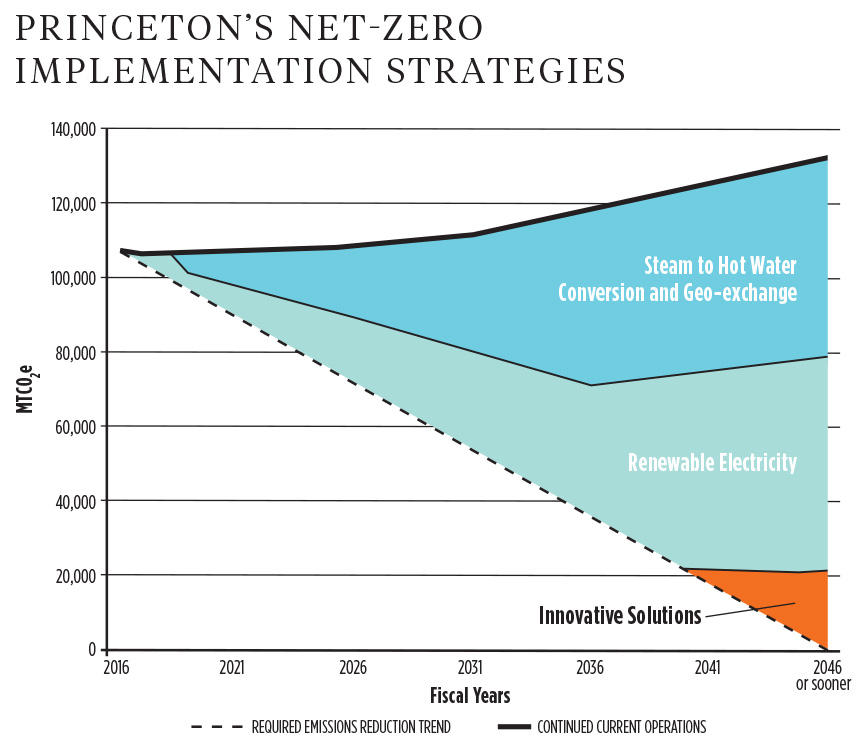

Princeton’s commitment to achieving net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2046 relies on a multipronged strategy, according to Sarah Boll, the University’s executive director of sustainability: transitioning to geothermal and solar energy, improving energy efficiency, and fostering sustainability engagement among students, faculty, and staff. Nearly half of the emissions reduction will come from geo-exchange, with the other half from renewable electricity. The remainder? “Innovative solutions,” as illustrated in the wedges diagram of Princeton’s net-zero implementation strategies.

“The reality is 20 years to net-zero isn’t that much time,” said Boll, who has been in her role at Princeton since April 2024, building on her corporate sustainability experience as the senior director of energy and sustainability at Marriott International North America. “Now is the time to identify innovations, specifically for greenhouse gas reduction. We need to stay on top of advancements in the energy sector.”

Princeton set its net-zero goal in 2019, aligning its sustainability ambitions with the University’s 300th anniversary. The strategy, outlined in the Sustainability Action Plan, has set the University on a transformative path. Yet, as Princeton advances toward this goal, critical questions arise: How are emissions reductions measured? What counts as progress? And does the University’s approach fully account for its broader environmental impact?

Princeton’s world-class research positions it to leverage innovations both within and beyond the University. Boll highlighted ongoing research on green hydrogen, the Andlinger Center’s AI innovations, and the Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory’s efforts to make nuclear fusion viable in the future.

So far, Princeton has achieved a 13% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions since the baseline year of 2008. Boll describes this as “on track” and anticipates acceleration in the coming years as the geo-exchange system and TIGER energy plant are more widely utilized.

Students like Matthew Peterson, a graduate student in public policy, are already seeing the impact. “From innovative geothermal and solar energy projects to electric buses, Princeton is putting its money where its mouth is,” he said. Other observable changes include the switch to compostable containers and cutlery at certain campus locations, such as the food gallery at Frist Campus Center.

However, the net-zero target currently excludes what the internationally recognized Greenhouse Gas Protocol calls “Scope 3” emissions — indirect emissions from the supply chain, including business travel, commuting, and the lifecycle impacts of goods like construction materials and food. These emissions are significant but remain outside Princeton’s primary carbon accounting framework. Boll noted that the University is working to calculate Scope 3 emissions by tracking 15 categories of data in accordance with the Greenhouse Gas Protocol. She expects the Scope 3 calculation and reduction plan to be included in the updated Sustainability Action Plan, due to be published in 2026.

Education is the basis for inspiring behavioral change to achieve campus-wide sustainability. The Office of Sustainability runs programs like EcoReps, which empowers students to lead initiatives such as clothing swaps, furniture resale events, and compostable cup programs for Reunions. Frida Ruiz ’25, a mechanical engineering major and former president of the Princeton Student Climate Initiative, sees students as key drivers of sustainability on campus. “Students have the opportunity to use Princeton’s resources not only to make the campus more sustainable but also to engage with the broader community and support local environmental efforts,” she said.

One behavioral intervention Boll and her team see as a success is the “Power is Ours” program, which targets laboratories — hotspots for electricity consumption on campus. Based on behavioral design principles, the program encourages energy-efficient practices among lab users. A pilot initiative at Icahn Laboratory, Frick Chemistry, Hoyt Laboratory, and Bowen Hall achieved a 35% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions from those buildings in nearly one year (May 2023 to March 2024) simply by reminding faculty and students to shut fume hoods when not in use.

While Princeton has made improvements in recycling, such as the S.C.R.A.P. Lab’s efforts to compost uneaten food, students have pointed out contradictions, like the abundance of free food and single-use plastics at campus events. Boll acknowledged that eliminating single-use plastics has been difficult, and the amount of waste diverted to landfills has remained stagnant since 2008. “There is an opportunity to do more,” she said. “We need to investigate the waste problem more broadly across campus.”

Ruiz added that due to contamination of recycling bins with nonrecyclable items, only about 23% of campus waste is actually recycled, according to data from the Office of Sustainability.

Looking ahead, Princeton’s progress toward net-zero hinges on two key factors: the expansion of geo-exchange and the carbon intensity (a measure of carbon dioxide emitted per unit of electricity consumed) of electricity it procures from outside sources. While the state of New Jersey aims to achieve 100% renewable electricity by 2035, uncertainties remain, particularly under shifting federal climate policies. Peterson expressed concern: “With the uncertainties around wind power in New Jersey, I hope Princeton sticks to its commitments.” If state efforts fall short, Boll said the University may explore large-scale off-campus power purchase agreements for green energy.

1 Response

Alex Zarechnak ’68

9 Months AgoNet-Zero’s Priority Waning

PAW’s April issue includes a major article, “Princeton Advances on Path to Net-Zero, But Challenges Remain,” and two letters to the editor “Los Angeles Fires” and “Climate Coursework” which indicate that our university community is not aware of the recent shift away from net-zero among governments and industries world-wide. Examples: 1. A Monmouth University Poll in April 2024 reports decreasing support for government action on climate change since 2018. 2. Breakthrough Energy, an umbrella organization funded by Bill Gates that works on a sprawling range of climate issues, announced deep cuts to its operations. Gates said in an interview, “I’m sad that the current priority of climate change in the rich countries has gone down a lot.” This shift away from net-zero was anticipated in two previous Conservative Princeton Association Expert Panels at Reunions, “Why Climate Change is NOT an Emergency” and “The Great Escape from Net-Zero Hunger Games” (both available on YouTube). As discussed in these panels, this shift is justified by a rigorous application of climate science and a recognition of economic pain resulting from net-zero ideology. Maybe Princeton University should get ahead of this curve?