More than 50 years after the end of the Civil War, a memorial to the Princeton alumni who lost their lives in the bloody conflict over slavery was carved into the marble walls of Nassau Hall’s atrium. Alone among American universities, Princeton chose to commingle the names of Union and Confederate dead, without noting which side they had fought for.

That reticence, says Princeton history professor Martha A. Sandweiss, grew out of the University’s antebellum history, and the deep ties to slavery that shaped a Northern school long known for its affinity with the South.

For more than four years, Sandweiss and some three dozen undergraduates, graduate students, and established scholars have explored those connections in a group research effort now known as the Princeton & Slavery Project, whose findings will be officially unveiled this month on a website and at a Nov. 17–18 scholarly symposium on campus. (Related events take place Nov. 16–19.)

From small personal stories and large data-mining efforts, researchers have pieced together a portrait of a Princeton with intimate but largely unacknowledged ties to the enslavement of African Americans: a university whose trustees, presidents, and faculty owned slaves; whose finances were shored up with slave money; and whose graduates sometimes went on to become apologists for America’s “peculiar institution.”

“On our campus — where the Continental Congress met, where the patriots won a victory against the British — human beings were enslaved,” Sandweiss says. “That’s the story of American liberty and freedom. Slavery was a part of it, and that’s true on our campus also. We are deeply and quintessentially American in that respect.”

Princeton is not the first university to investigate its pre-Civil War ties to America’s original sin. In 2003, Brown University, which is named for a family of slave traders, convened a committee to study the issue and recommend an official response, and since then, more than 30 other schools have followed suit, estimates Leslie M. Harris, a Northwestern University history professor and co-editor of a forthcoming essay collection on universities and slavery.

Unlike the research efforts at some other universities, the Princeton & Slavery Project was not an administration initiative, although it has received funding from a number of groups affiliated with the University, led by the Humanities Council. In a statement provided to PAW, President Eisgruber ’83 suggested that independent research can result in “richer, more stimulating, and more varied work than would any official history published or approved by the University administration.”

The research projects at universities across the country stem from American historians’ renewed interest in slavery, and particularly in slavery’s importance outside the South, Harris says. But she also connects the work to truth-and-reconciliation efforts in countries like post-apartheid South Africa. “That put on the map this idea that it is fruitful for societies to really confront their histories,” she says. In some ways, universities are “very conscious of their past. They hold up their famous alumni, they talk about the founding,” she says. “But it’s another thing to investigate these other kinds of histories.”

Princeton’s links to slavery are less direct than those of some other schools, the Princeton & Slavery researchers found. Unlike Georgetown University, which stayed afloat using the proceeds from an 1838 sale of 272 Jesuit-owned slaves, Princeton — as an institution — apparently never owned slaves or rented their labor. And no evidence supports the oft-repeated claim that Princeton students from the South brought their slaves to campus.

But slavery was woven into campus life nonetheless. According to essays on the project website, 16 of the University’s 23 founding trustees “bought, sold, traded, or inherited” slaves, and Princeton’s first nine presidents, who served between 1746 and 1854, all held slaves at some point in their lives — although, in a strange cognitive dissonance, several also preached that slavery was morally wrong.

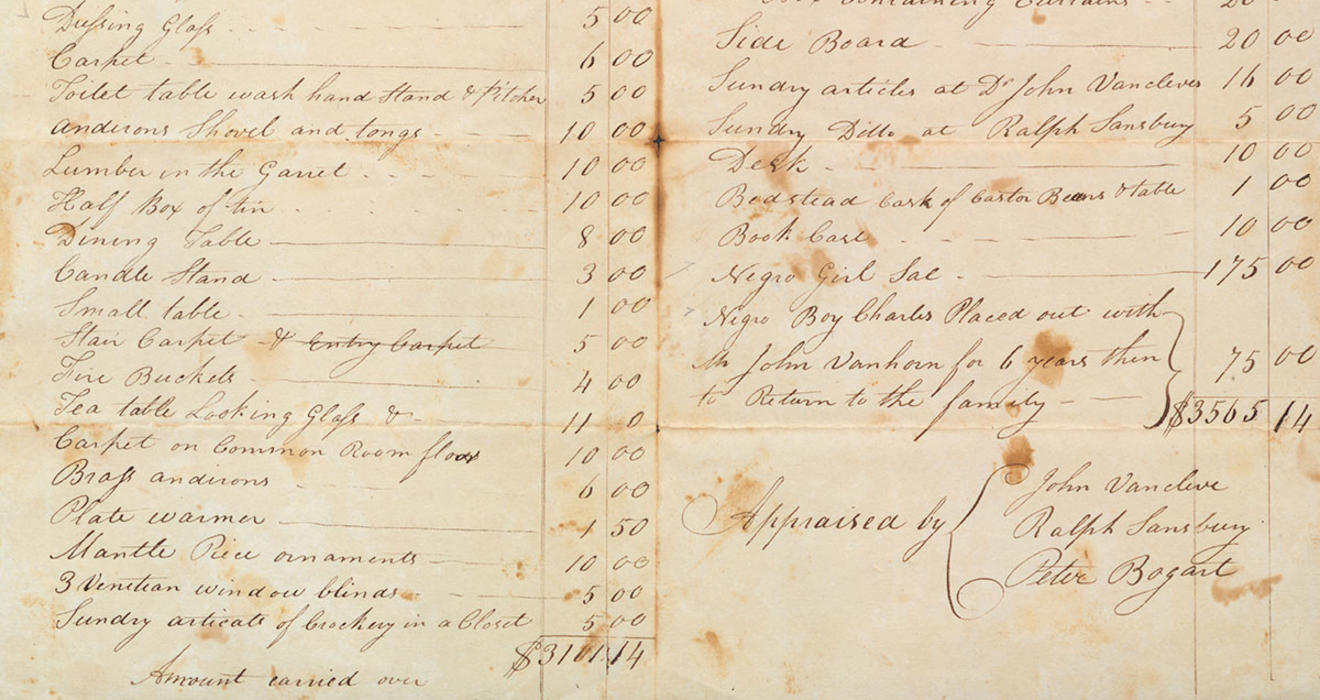

In 1766, after the death of the University’s fifth president, the Rev. Samuel Finley, his executors advertised an auction of his property — including six slaves — to be held outside the President’s House, now known as Maclean House. Nearby stood the two sycamore trees Finley had planted earlier that year, in what campus legend inaccurately holds to be a commemoration of the repeal of the Stamp Act, a milestone on the road to American independence.

Princeton’s entanglement with slavery mirrors New Jersey’s status as a nominally anti-slavery Northern state with unusual sympathy for the South. New Jersey was the last Northern state to abolish slavery, voting in 1804 to outlaw the institution with a gradualism that favored the interests of slaveholders and left a handful of slaves as late as 1865. Abraham Lincoln lost the popular vote in New Jersey in both 1860 and 1864, and the state initially refused to ratify the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which banned slavery.

“This is a very peculiar experience in the North,” says Craig Hollander, an assistant professor of history at the College of New Jersey, who worked with the Princeton & Slavery Project as a postdoctoral fellow in 2013–15. “There were just a lot of economic and cultural ties to the South, and Princeton played an extremely important role in cultivating those ties.”

But if New Jersey was an extreme case, the North was also more closely implicated in slaveholding than traditional accounts acknowledge, scholars say. “Too many people simply still see slavery as a Southern question, a Southern problem,” says Eric Foner, a Columbia University history professor who directs Columbia’s investigation into its own links to slavery. “But for a long time, slavery was a very significant institution in all of the Northern colonies, and indeed states. That’s important for people to realize, how deeply embedded slavery is in the history of the entire country.”

Although Sandweiss has published several books about 19th-century American history, she is not a specialist in the history of slavery, and as a relative newcomer to Princeton (she joined the University in 2009, after a long career at Amherst College), she knew little about Princeton’s history when she taught the first Princeton & Slavery undergraduate seminar in 2013.

“I can’t overemphasize how ignorant I was in the beginning,” Sandweiss says. “We didn’t really know what we were looking for. We didn’t know what the low-hanging fruit for this story would be, we didn’t know where we would find the good stories, we didn’t know where to look in the archives.”

Initially, University archivist Dan Linke, who helped Sandweiss and her students track down sources, wasn’t optimistic. “Because of the nature of how enslaved persons are recorded in history — no last names, just as a number in a census — I really didn’t think she was going to find a lot,” he says. The project’s biggest surprise, Linke says, is “how easily undergraduates asking fairly simple questions have found so much.”

In the seminar, versions of which Sandweiss or her postdoctoral fellows have taught each year since 2013, students pored over a wide array of sources: letters, diaries, wills, sermons, speeches, newspaper advertisements, census data, genealogy records, student directories, the minutes of University trustee and faculty meetings. Some sources, such as newspaper databases, were newly digitized, available online only in the past decade; others had been gathering dust in University archives for generations.

When Hollander first arrived on campus and saw the archival riches awaiting him, “my eyes just lit up,” he says. “You rarely get opportunities to see these kinds of primary sources and explore them — not for the first time; people had been perusing them for years — but with fresh eyes. We are now looking for a very different story than people in the past had looked for.”

For undergraduates, the seminar offered a chance to do original work, rather than replicate the findings of established historians. “The greatest thing about this course was there were no rules,” says Sven “Trip” Henningson ’16, a history major who took the class in his last semester at Princeton and has continued to do research for the project since graduating, during weekend breaks from his consulting job. “You could find whatever you wanted. Whatever you dug up was fair game.”

Lesa Redmond ’17 enrolled in the course as a sophomore, promptly switched her major to history, and ended up writing her senior thesis on slavery connections in the family of John Witherspoon, Princeton’s sixth president. Witherspoon, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, opposed immediate abolition and owned slaves — even though he tutored several black men to prepare them for work as Christian missionaries.

Three hundred years of Witherspoon genealogy made for a family tree so sprawling that it wouldn’t fit on a single sheet of paper; Redmond had to post it on her bedroom wall, where it greeted her when she awoke each morning. “I’ve thought a lot about what it means to be an African American student enrolled in Princeton studying the history of this university,” says Redmond, who plans to attend graduate school in history. “That was very powerful for me.”

Among the tasks tackled by students in successive seminars was the verification and documentation of a piece of conventional wisdom: that Princeton was the “most Southern” of what now are the Ivy League universities, in the composition of its student body if not in its geographical location.

Because Princeton has a file for virtually every undergraduate ever enrolled, students and archivists were able to build a spreadsheet listing everyone who attended Princeton before the Civil War — 6,593 men from the classes of 1748 through 1865. Then researchers set out to determine where they were from, turning to student catalogs, biographical dictionaries, and online genealogical records to verify each person’s origins.

The work culminated in what project participants fondly call the “hackathon,” held one night in early 2016, when a dozen student researchers gathered over pizza at the Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library to nail down the last 2,200 names, with Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton soundtrack playing in the background.

The results were illuminating. Between 1746 and 1863, the research showed, the proportion of Southern students at Princeton averaged 40 percent. From 1820 to 1860, at a time when the enrollment at Harvard and Yale averaged 9 and 11 percent Southern, 12 Princeton classes enrolled a majority of Southerners, with Southern enrollment in the Class of 1851 reaching 63 percent.

Princeton’s strong Southern flavor influenced the political climate on campus, the research suggests. Violence occasionally flared; project researchers uncovered a disturbing account of an 1835 incident in which University students manhandled a visiting abolitionist and ran him out of town. But antebellum Princeton mostly dealt with slavery — the most fundamental political issue of the day — by muting discussion of it, sacrificing the University’s vaunted commitment to liberty on the altar of community harmony.

“There was this sense that if this institution could do it — could not only keep itself together but thrive as a community of both slaveholders and non-slaveholders — then the country could do the same thing,” Hollander says. “They thought of themselves as a model for the nation.”

In the decades before the Civil War, as the national debate about slavery intensified, Princeton grew more conservative on the issue. In 1850, a Commencement speaker told newly minted graduates that abolishing slavery would be tantamount to invalidating Christianity and welcoming anarchy. “That 63 percent of our students came from the South in 1851 helps us to better understand the conservative political culture on campus, which we could document in other ways,” Sandweiss says. “You put those two bits of data together, and you get it.”

For much of Princeton’s history, slave money also bolstered the University’s finances. As president from 1768 to 1794, Witherspoon aggressively recruited Southern students and their tuition dollars, and Princeton’s geographical reach grew as slavery spread westward. “You can map almost a 1-to-1 correlation of the cotton boom in Mississippi to the attendance of students from Mississippi,” says Henningson, the 2016 Princeton graduate.

In an era when the elite universities of today were still struggling startups, Princeton was not the only school that turned to slave money to shore up shaky financial foundations, says Hollander. “It was not out of the question that these places would just collapse. Plenty of schools did during the 19th century,” he says. “One of the reasons why they’re willing to make these kinds of compromises is because they were worried about the bottom line.”

And the financial ties did not end with emancipation: A century after Witherspoon’s presidency, Moses Taylor Pyne 1877 drew on his grandfather’s fortune — a fortune amassed by supplying ships and financial services to slave-dependent sugar plantations — to become one of Princeton’s most generous and influential benefactors.

As Princeton’s antebellum graduates moved on into their adult lives, they spread across the country, creating networks that solidified the University’s influence and its ties to slave-owning families and communities. Some alumni were firmly anti-slavery, or dedicated to gradualist methods of abolishing it: Princetonians were disproportionately involved in the American Colonization Society, for example, which sought to end slavery by returning freed blacks to Africa. But many other Princeton graduates returned to their Southern homes to become lawyers, ministers, and statesmen who advocated the continuation and expansion of slavery.

“We were the most national university in America, hands down,” Sandweiss says. “What happened at Princeton had a very broad national impact.”

While the Princeton & Slavery Project has excavated neglected corners of the University’s past, such projects also carry lessons for how we understand the place of institutions of higher education today, researchers say.

The work makes clear how deeply universities are embedded in a social context, scholars say. “We tend to think of universities as ivory towers, but they are not removed from their societies,” says Harris, the Northwestern professor. “They are part of the society, and so they reflect the good, the bad, and the ugly, and the history of slavery in universities shows that.”

A deeper understanding of historical context can also inform contemporary debates, like the one that raged at Princeton in 2015–16 over whether to remove Woodrow Wilson’s name from campus buildings, scholars say. “The debate about Woodrow Wilson would have been a more informed conversation if we had thought about him in the context of the much longer history of racial thinking on our campus,” Sandweiss says. “He didn’t just appear from nowhere. He appeared on a campus that was hospitable to very conservative racial thought.”

“The debate about Woodrow Wilson would have been a more informed conversation if we had thought about him in the context of the much longer history of racial thinking on our campus.”

— Professor Martha Sandweiss

Understanding the past has implications for the University’s future, as well. “Knowing your past can help you craft an identity that either looks like that past or doesn’t, depending on what you want,” says Redmond, the 2017 Princeton graduate. “But if you don’t know what you were in the past, it’s very hard to go forward.”

How should universities go forward when projects like this uncover ties to slavery? Other institutions have built on the results of their slavery investigations to make amends, both concrete and symbolic. Georgetown is offering preferential admission status to the descendants of the enslaved people it sold; Brown invested in the local public school system, erected a campus slavery memorial, and established a research center for the study of slavery. Eisgruber’s general statement to PAW did not address steps the University may take in response to the Princeton project’s findings.

“When you look at the institution of slavery honestly, and you acknowledge your complicity in it, then the next step has to be some kind of repair, it would seem to me,” says Melvin McCray ’74, a journalist, filmmaker, and educator whose documentary about Princetonians’ family ties to slavery will premiere during the weekend of the Princeton & Slavery symposium. “What kind of repair or reparation is another question. But it seems to me that it would be only natural to want to make amends.”

Those amends might include a commitment to righting contemporary inequities — social, economic, and educational — that stem from slavery, some suggest. Elite universities like Princeton and Columbia are “very eagerly engaged in promoting diversity among their student bodies,” says Foner, the Columbia professor. “Whether more should be done, whether this history tells us to do more along those lines, I don’t know.”

Ultimately, historians can only provide the information on which to base a course of action, Princeton & Slavery researchers say. What that course of action should be is a decision that the University community will have to make together.

“I hope in the end it’s a project that makes Princeton proud — we can now look at ourselves and try to understand ourselves more fully,” Sandweiss says. “Then we’ll figure out how to reckon with it.”

Deborah Yaffe is a freelance writer based in Princeton Junction, N.J. Her most recent book is Among the Janeites: A Journey Through the World of Jane Austen Fandom.

Clarification: The article was updated in October 2023 to reflect new information regarding John Witherspoon.

18 Responses

J.D. Leza *00

7 Years AgoGracias

Thank you, PU, yet again!

Ralph D. Nelson Jr. *63

7 Years AgoNew Jersey’s History With Slavery

“Our Original Sin” (feature, Nov. 8) states that New Jersey was the last Northern state to abolish slavery. The legislative history on slavery has been a slippery fish ever since the Constitutional Convention of 1787. There the delegates artfully avoided using the term “slaves,” referring to them as non-free “other” persons worth only three-fifths of a person for representation in the U.S. Congress (Article I, Section 2) and remanding them (if they fled slavery) to the “party to whom labor may be due” (Article IV, Section 2).

New Jersey’s 1804 Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery provided that male children of enslaved women could be held in slavery until age 25 and females until age 21. Those enslaved before passage of the 1804 law remained enslaved for life. Under the 1846 New Jersey Act to Abolish Slavery, existing slaves were renamed as apprentices, who could be sold only with their written consent. Children born to them were free from birth. Under similar evasive terminology, slavery was practiced legally in several Northern states until the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution went into effect in December of 1865. It would be more accurate to say that New Jersey tied for last place with several other states in the date of prohibiting the practice of slavery.

Norman Ravitch *62

8 Years AgoI wrote an article in the...

I wrote an article in the 1980s for ENCOUNTER on the Armenian genocide you might want to look at. At the time German diplomats and missionaries in Istanbul tried to help the Armenians. It is not true that, as Hitler pretended, this genocide inspired the WWII genocide of the Jews.

Norman Ravitch *62

8 Years AgoMuch as I like to be agreed with...

Much as I like to be agreed with I think Larry Dickson's use of my views to support a totally different issue, abortion, is not legitimate. So I demur.

Clarence Thomsen

8 Years AgoPrinceton & Slavery?...

Princeton & Slavery? hahahahhahahhahahah THE PEACE MAKERS

The concept of slavery in America is bigoted and only seeks to segment our inert social fabric.

Children today are misdirected because they are not told the truth about slavery as an institution — worldwide.

The majority of the Europeans who settled this country, as far back as the early 1500s to 1600, did not come here because they were rich. They came here out of slavery, poverty and social degradation – as slaves.

The Irish, dying by the millions on the Ulster plantations. The world of the Britains created under slavery by the Angles, Jutes and Saxons. The word England itself comes from the word Angle Land.

We can go on and on with this conversation all the way back to the Roman Empire with the brainless subjects who actually think Caesar was a great emperor; with men being slaughtered daily and all of the women and children being sent into slavery and prostitution. Many ethnic groups including Italians and Germans tasted the power of the empire.

The state of Germany itself did not abolish slavery until late 1585; and even then, it still remained virtual slavery due to the wretched state of the economy and social structure. German people still remained in the same wretched state as if still in slavery.

It seems as though the same bigoted Southern mentality is still with us today, with politicians still working feverishly to retain false images for the European concept of money and power. Taking a close look at why this country has retained greatness is because all of the wars fought are fought ethically and consciously trying to eliminate the antagonistic and sadistic behavior of European culture. Why are Nazis still allowed to march in American cities — after two world wars?

When intelligent and trustworthy Americans such as Lincoln and Grant come to our aid again, and begin to truly educate the public, then we will begin to have a truly democratic society.

Larry Dickson *71

8 Years AgoI agree with Norman Ravitch,...

I agree with Norman Ravitch, and for a reason that may shock many of you. He draws attention to the Holocaust, whose victims were not desired as workers, but as corpses. I say look away from antebellum history and mid-20th-century history to the corpses we are making in our very own oppression of the innocent. Nobody has any right to condemn slavery unless they condemn abortion.

As World War II was drawing to a close, Pope Pius XII, quoting St. Augustine, said: "Change the heart and the [work] will be changed. Eradicate [greed] and plant charity. Do you want peace? Do justice, and you will have peace. If therefore you desire to come to peace, do justice; avoid evil and do good. This is to love justice; and when you have already avoided evil and done good, seek peace and follow it." (Communium Interpretes Dolorum)

In other words, get the beam out of our own eye before condemning the mote in our dead ancestor's eye. Otherwise we are just moralizing poseurs.

Norman Ravitch *62

8 Years AgoFrankly I am more than...

Frankly, I am more than disgusted with all the political correctness about slavery and Confederate monuments. Before the Declaration of Independence, no one really believed that all men were created equal, and slavery was not considered more than a social practice that could be problematic. Ancient history supported slavery; Aristotle wrote that some were natural-born slaves without specifying who these people were. The Bible, of course, did not in either the Old or the New Testament condemn slavery, and Princeton's Calvinist leaders fully understood that. As for Confederate monuments, we need not emulate the Soviet Encyclopedia, which periodically sent subscribers new versions of certain pages which they were required to substitute for old and now-erroneous ones. Should we really rewrite our past in this way? If we should, then universities and other Christian institutions should recognize the evil they did to Jews for some 1,600 years, resulting finally in the Holocaust. We can sympathize with blacks when they pass a Confederate monument, but why not sympathize with Jews who every time they pass a church, a statue of a saint who specialized in anti-Jewish homilies, etc., or written monuments to vicious anti-Semitism feel pain and sorrow? The Jews suffered much worse atrocities than Afro-Americans and over a much longer period of time. No one ever tried to eliminate every living black person they could get their hands on; quite the contrary, they were desired as workers. Jews were more desired as corpses by WWII Christians than as workers. I have had enough! And I am not a supporter of Donald J. Trump, thank you very much.

Martin Schell ’74

8 Years AgoIt’s understandable that...

It’s understandable that people focus on the most egregious event in a category and ignore historical precedents. Pain narrows our concentration.

As a fellow Jew, I venture to remind Dr. Ravitch *62 that many of our co-religionists still think the Nazi atrocity was the only holocaust. In fact, the Armenian holocaust preceded it and there’s good evidence that Germany used it as a model. They also used the anti-miscegenation laws of Virginia as a model in their promotion of eugenics, a self-aggrandizing movement if ever there was one.

Political correctness often waves a revolutionary banner, seeking retribution while claiming “the first revolution is in your mind” with Copernicus being cited as an example. However, the mindset it promotes is more like Ptolemy’s vision: at the center of the universe are humans, specifically MY identity group; then allied identity groups are arrayed in concentric circles according to how closely their intersectionality supports MY agenda.

The challenge of our times is to see history clearly and then transcend it. No descendants — of victims or of perpetrators — should be penalized.

Unfortunately, the fiery awakening of the past in recent years is blinding us to carnage occurring in the present, namely perpetual warfare promoted by each of our 21st-century presidents. Incessant media coverage of domestic politics seems like bread and circuses, distracting attention from overseas deaths that are happening at this very moment.

Alex Wellford ’64

8 Years AgoAndrew Jackson focused much...

Andrew Jackson focused much of his presidency on preserving the Union, fighting the hotheads in a very wealthy South Carolina. When those later hotheads fired on Fort Sumter, Jackson might have told them, if he had still been around, "You are on your own." A form of slavery with sharecropping continued after the war. It was a shame that something did not more quickly replace the dependency of manual labor to pick cotton.

Norman Ravitch *62

8 Years AgoWhy Wilson Deserves Criticism

Published online Jan. 4, 2018

Woodrow Wilson 1879 has become controversial — especially in light of the essays on Princeton and slavery in the Nov. 8 issue of PAW. Which of his misdeeds deserve the most condemnation? Is it permission for The Birth of a Nation to be seen at the White House? His resegregation of some federal department during his presidency? What exactly? To me this is all a guilt trip by white liberals. Wilson deserves considerable condemnation for something quite different.

I have not even started to discuss the evils of his administration as president of Princeton. Too bad the 25th Amendment had not yet been passed!

Philip Seib ’70

8 Years AgoPrinceton Reckons with its Connections to Slavery

During the past several years, Princeton has adopted an approach of educate, not eradicate, in its appraisal of its past. Because of this, its future will be built on a firmer foundation.

Norman Ravitch *62

8 Years AgoInstead of having Princeton...

Instead of having Princeton apologize for slavery back then, why not condemn its existence today? Largely in Muslim lands.

Jim Studdiford ’65

8 Years AgoPrinceton Reckons with its Connections to Slavery

The “Princeton and Slavery” issue masterfully detailed the antebellum Princeton history so closely linked to slavery. Northern and Southern sentiments regarding slavery were complex, and even Union and Confederate soldiers were not in uniform agreement on the issues for which they fought and died.

Josiah Simpson Studdiford 1858, a Northern Unionist, enlisted as a lieutenant in the 4th New Jersey Infantry regiment. This decision met with the disapprobation of his four brothers, all Princeton graduates. Thus his mother received his letters depicting battles and historic figures (now in the Princeton University archives).

To wit: He saw Lincoln (“Uncle Abe on horseback ... his legs thin make an appalling scene”) and McClellan (“his legs stout”), and was captured at Gaines’ Mill and sent to Richmond, where he met Gen. Robert E. Lee (“his treatment was exceeding courteous”). From Libby Prison, he wrote, “I lived on one hard cracker and half-cup of coffee a day ... Stonewall Jackson’s men live on such fare and fight on it and I am sure we ought to.” Exchanged back to the North, Josiah took command of the 4th NJ and on Aug. 27, 1862, he was ordered “to hold the Bridge at Bull Run”; then the chilling rebel yell of Stonewall’s Brigade rose, and the “greybacks began whanging away” — unleashing a hail of gunfire. Josiah retreated. He died two weeks thereafter leading a victorious charge at the Battle of South Mountain. He is buried at Lambertville, N.J.

Thus memorialized on the atrium wall in Nassau Hall — a Yankee who respected, even revered, his Confederate counterparts.

George Barlow *53

8 Years AgoPrinceton Reckons with its Connections to Slavery

I was a graduate student at Princeton starting in 1950. My studies were done in the biology department in the laboratory of Professor Wilbur W. Swingle, located on the basement level of Guyot Hall. Professor Swingle was one of the world’s leading authorities on the adrenal cortex, an endocrine gland, the secretions of which are crucial not only to our well-being but to life itself.

Much of the experimental effort centered on the secretions of the adrenal cortex and the identification of the hormone(s) secreted by that endocrine gland. This required the use of dogs whose adrenal glands had been removed. The difficult surgery was, I believe, developed by Dr. Swingle, and he would never operate without Langford’s assessment of the dog’s health and unless Langford was present as the anesthesiologist. Langford also was the most trusted postoperative caretaker of the dogs, and he taught students the proper, humane care and assessment of both pre- and post-experimental animals. But there was so much more interaction between Langford and the white graduate students. For example, he helped me and my new wife find our first automobile (a used green 1950 Chevrolet).

Possibly Langford’s employment record still exists wherever those records are kept. I know of no picture of Langford, and I wish I had one. It is so sad that a man so important in mainline research at a great university remains unknown.

Your article on Joseph Henry and his black assistant, Sam Parker, inspired me. And now we know of two black men who worked in the shadows at Princeton.

Photo of Langford Bolling courtesy Romus Broadway

Maurice D. Lee ’46 *50

8 Years AgoPrinceton Reckons with its Connections to Slavery

As you can see from my class numbers, I have been reading PAW for a lot of years, especially while my late wife, Helen, was Class Notes editor in the 1970s. The issue on Princeton and slavery is as good an issue as I have ever seen, full of new, interesting information and very well written. It would have greatly pleased Helen, who was an enthusiastic supporter of African American rights long before it became popular to do so. Congratulations, and keep up the good work.

Andrew Tynes ’17

8 Years AgoPrinceton Reckons with its Connections to Slavery

If Princeton actually cared about making right with its slave-ridden past, it would provide reparations to the descendants of slaves who worked there.

(posted on Twitter)

Harold Scott Gurvey ’73

8 Years AgoPrinceton Reckons with its Connections to Slavery

Distressing as it may be, we cannot hide from our history. We must reflect on it and learn. My congratulations to PAW for its wonderful reporting on the Princeton & Slavery Project, and of course to all the Princeton scholars who contributed to the project and website.

Robert Schultz ’76

8 Years AgoPrinceton Reckons with its Connections to Slavery

It’s interesting that we’re using our standards today to judge people making decisions 150 years ago, based on what they thought was true then. We want to tear down statues, change the names of buildings, etc. I wonder if in 150 years, when it’s understood that babies in the womb are people and have as much right to life as anyone else, whether people living then will be tearing down the monuments to prominent figures living today who encourage abortion and are party to killing millions of those unborn people. Of course, many people today, maybe even a majority, believe that abortion is the “right thing to do” for many reasons. I wonder if that will make a difference in how they are viewed once the truth is known and people are aware that we’ve been slaughtering millions of innocent people. Food for thought ...