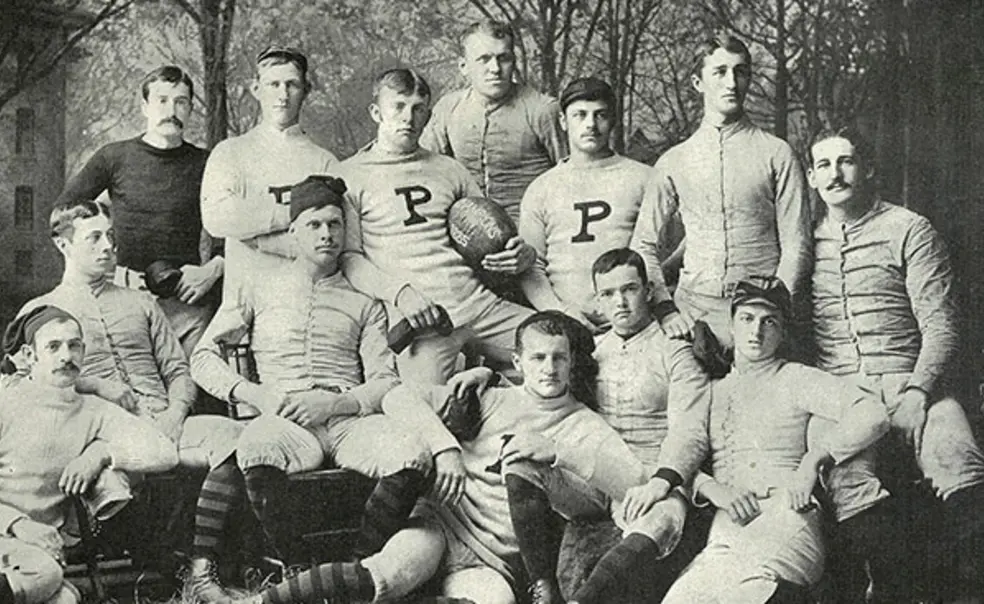

Six games into the 2018 season, Princeton football remains undefeated, scoring more than 48 points per game — a pace that ranks as the team’s most productive since the 1880s.

Since the program’s scoring record of 637 points was set in 1885, football has changed a great deal, beginning with a period of reform at the start of the 20th century, when the game’s role on campus was frequently discussed in PAW’s pages.

In the fall of 1902, the magazine published “an important letter on an important subject” by Henry B. Thompson 1877, then a member of the Graduate Advisory Committee of the Princeton University Athletic Association. Thompson wrote about “Football As It Is Fought,” worrying that football players were subject to dangerous levels of non-academic pressure and physical risk — and that the game seemed to abide by a unique “code of ethics” separate from that of other sports. He advised that the University “correct these evils” within the game.

Princeton football was a juggernaut of campus life, but Thompson’s criticisms were not unusual. In 1905, Princeton students won the annual Harvard-Princeton debate by arguing that football was “a detriment rather than a benefit” to the American college student, both physically and mentally. By the spring of 1906, Harvard was planning to suspend its football program unless a new intercollegiate committee was formed to revise the rules of the game.

After the committee was formed, PAW provided extensive coverage of its recommendations, which included the introduction of the forward pass, a change that the editors predicted would “prove of little consequence” due to the restrictions that governed it (see full story below). But in the opening game that fall, Princeton managed just one rushing first-down in a win over Villanova. Left end Lewis Wistar 1908 caught two passes for touchdowns.

The 21st-century Tigers have continued to embrace the value of the forward pass, scoring a school-record 30 touchdowns through the air in 2017 and keeping pace with an Ivy League-best 18 passing touchdowns so far this season. Princeton hosts three of its final four games — vs. Cornell Oct. 27, Dartmouth Nov. 3, and Penn Nov. 17 — and travels to rival Yale Nov. 10.

Final Action on the Football Rules

(From the April 21, 1906, issue of PAW)

The Football Rules Committee held another meeting in New York on April 14th — the final session, according to announcement, for this year’s revision of the code. It was largely devoted to the proper phrasing of the new amendments, the only vital legislation being the revocation of the rule tentatively adopted at a former meeting, weakening the defense by the withdrawal of one man from the line. The effect of this is to leave the defense the same as it has been heretofore.

The net results of the committee’s numerous meetings are:

- The ten-yard rule — doubling the former distance to be gained in three downs, in order to retain possession of the ball.

- The on-side kick — after a kick, all players to be on side as soon as the ball touches the ground.

- The high tackle — no tackling below the knees, except by the center, guards and tackles on defense.

- The forward pass.

- The center, guards, tackles, and one end of the attacking team must be on the line of scrimmage when the ball is put in play; any one lineman, however, allowed to go back at least five yards, presumably for a kick.

- Severe penalties for violations of the rules, unnecessary roughness, unsportsmanlike conduct, etc.

Just how much the game itself will be changed by these alterations in the rules will remain, of course, a matter of speculation until they are put to the test on the playing fields next season. It seems plain, however, that the new legislation will bring about no radical departures in American football. The on-side kick rule will undoubtedly encourage punting, and is a distinct advance toward opening up the game; and now that the committee has decided not to weaken the defense, the ten-yard rule will have a similar effect. The high tackle and forward pass will, we believe, prove of little consequence, for the value of both of them has been very much impaired by restrictions. Only one forward pass is allowed on a play; it must be made by a player who was behind the scrimmage line when the ball was put in play; with the exception of the ends, it cannot be received by a man who was on the line of scrimmage when the ball was put in play; it cannot be lobbed over the line of scrimmage; if passed over the goal line it’s merely a touchback; it is not allowed by the side not putting the ball in play; and if the ball touches the ground before being touched by a player, it goes to the opponents. With so many restrictions and the chance of losing the ball anyhow, that one forward pass to the play will scarcely revolutionize the game. And the high tackle rule is practically nullified by this subsequent modification: “It shall not be a foul tackle if the tackler’s arms or hands slip below the knees after the tackle has been made” — an old trick which the present generation of players will not be slow to learn.

The best that can be said of the new football legislation is that it is a step in the right direction — the direction of opening up the game. To that end, more radical changes will unquestionably be demanded next year. By persisting in allowing five men back of the line, the committee has failed to eliminate the possibility of mass play; but at any rate those abominations guard-back and tackle-back have been prohibited, a consummation for which let us all be devoutly thankful.

No responses yet