A Bond Forged While Advancing Mathematics

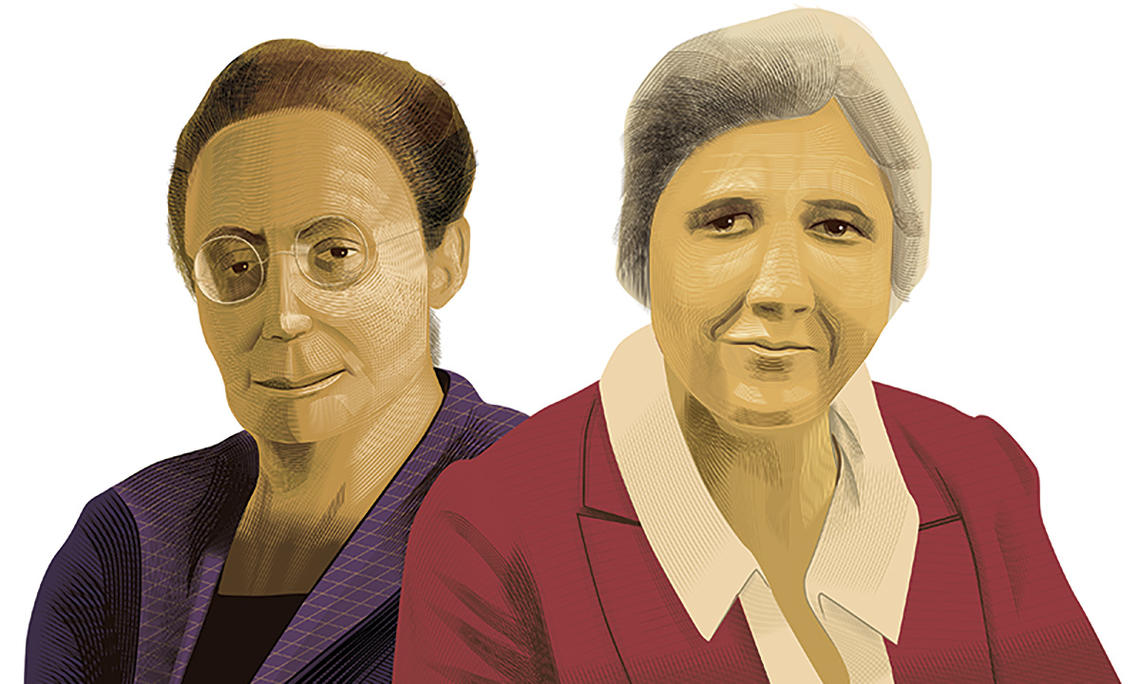

Emmy Noether (1882-1935) and Anna Pell Wheeler (1883-1966)

Emmy Noether and Anna Pell Wheeler knew each other for just a few years. But they were important years. Their story shows how universities can advance a field just by inviting people in.

When Noether was college-aged, women weren’t allowed to enroll in German universities. She audited classes for years, until finally a new law let her enroll at the University of Erlangen. In 1907, she received a Ph.D. in mathematics summa cum laude. Afterward, the university, recognizing her rare talent, let her give lectures — though of course without pay.

Once, when a famous colleague was scheduled to give a lecture, the men debated whether Noether, as a woman, could attend. Finally, one of them said, “Gentlemen, this is an academic society, not a bathing club.” That settled it: Noether could hear the lecture. From behind a screen.

In 1915, Noether moved to the University of Göttingen, then called “the world center of mathematics.” There, she gave lectures on behalf of the mathematician David Hilbert. In 1922, her department successfully petitioned the government to finally make her a professor. But in 1933, when the Nazi regime purged the academy of non-Aryans, Noether, who was Jewish, lost her hard-won position.

Anna Wheeler, meanwhile, grew up in Iowa. She piled up degrees from the University of South Dakota, the University of Iowa, Radcliffe College, and the University of Chicago, where she earned a Ph.D. She, too, faced sexism — she told an acquaintance, “I had hoped for a position in one of the good [public universities] … but there is such an objection to women that they prefer a man even if he is inferior both in training and research” — but she ultimately succeeded, becoming a mathematics professor at Bryn Mawr College. She married a Princeton professor named Arthur Wheeler and moved to Princeton, where she was active in the mathematics community while still teaching at Bryn Mawr.

In the 1930s and 1940s, Princeton’s mathematics community worked heroically to bring refugee scholars to the United States. Wheeler was part of these efforts, helping women scholars in particular to find places at Bryn Mawr. Thanks to her, Noether was able to come to the United States as a visiting professor at Bryn Mawr and a lecturer at the Institute for Advanced Study. To this day, Princeton is justly proud of its association with the very eminent Noether. In those years, Göttingen ceased to be the world center of mathematics — and Princeton took that title.

“I had hoped for a position in one of the good [public universities] … but there is such an objection to women that they prefer a man even if he is inferior both in training and research.”

— Anna Pell Wheeler

In Germany, Noether heard that “the people at Bryn Mawr were very sophisticated and everyone wore hats.” So when Wheeler picked her up in Philadelphia, Noether was wearing a fancy hat — and feeling very ill at ease. When she saw that Wheeler, though smartly dressed, was hatless, she gleefully threw her hat away.

Back then, the official hobby of mathematicians was hiking. Wheeler owned a cottage in the Adirondacks, and she took students on nature walks and taught them bird calls. Soon, she and Noether, who became great friends, were both leading mathematical hikes in Princeton and Pennsylvania.

A student wrote to Wheeler, upon her retirement, about how a great professor moves her field forward by helping others to belong in it: “I remember the foot marks on the wall of the math seminar room. You had the habit of standing on one foot … . I remember your stopping the car at an intersection in the middle of nowhere while you tried to identify a bird call which only you had heard … . But most of all I remember my father’s words after he met you on Commencement Day in 1930. The thought of his daughter aspiring to be a female mathematician was a bit horrifying to him. However, after he met you, he said, ‘Such a woman I would like you to be.’”

2 Responses

Bruce Blackadar ’70

3 Months AgoQuestioning Princeton’s Connection to These Eminent Scholars

As a mathematician, I read with interest the article in the January PAW about mathematicians Emmy Noether and Anna Pell Wheeler. They were certainly remarkable figures.

But I couldn’t see the Princeton connection, other than that Wheeler was married to a Princeton professor. And I both chuckled and gagged a bit to read about the “heroic efforts” of the Princeton mathematics community to bring refugee scholars to the United States (maybe true with respect to male mathematicians), and that “to this day, Princeton is justifiably proud of its association with the very eminent Noether.” Huh? What association? I didn’t see Princeton offer her a professorship, even though she was a world-class mathematician who was at least the equal of anyone on the Princeton faculty at the time, or the European men Princeton hired during that era. The best she could do was a visiting professorship at Bryn Mawr and a lectureship at the Institute for Advanced Study (which has no connection with Princeton University).

It may have been a different time, but Princeton did not cover itself with glory here and should not pretend it did.

Donald Groom ’56

11 Months AgoRemembering Anna Wheeler

After her retirement from Bryn Mawr, Professor Wheeler maintained contact with students, hosting them for tea at her house and as guests at her cabin in the Adirondacks. This included Bryn Mawr class of 1961 physics majors Jean Hebb and Melinda Flory (my future wife), as well as Clara McKee. Clara was an English major, but her mother, Ruth Stauffer McKee, had gotten her Ph.D. at Bryn Mawr under the supervision of Emmy Noether. Noether died unexpectedly after surgery in 1935 at age 53, before the doctorate was awarded. We understand that the work was completed under Professor Wheeler.

The photo above of Professor Wheeler is from a garden party to celebrate Clara, Jean, and Melinda’s graduation. I obtained it from Jean Hebb Swank, who tells me it was taken by math student Carol Duddy. The slightly cut figure on the left is Melinda’s father, Paul Flory, who would win the Nobel Prize in chemistry in 1974. The cut figure on the right is Melinda’s sister Susan, Bryn Mawr ’59 (mathematics).

Melinda somehow inherited Anna Wheeler’s teapot, which we eventually returned to Bryn Mawr. My own memories from Melinda were supplemented by Susan Flory Springer and Jean Hebb Swank.